Planning a protest is a lot like planning a quinceñera, Sheridan Lagunas, the Field Communications Manager at United We Dream, told the students seated around him. It’s all about the logistics. Mikaela Pozo, a rising senior at T.C. Williams High School in Arlington, Virginia smiled at the comparison. News was in the air of the previous day’s ICE raid in Mississippi that left children returning from their first day of school to find their parents gone, and the emerging activists participating in Summer of Dreams were preparing for an event in front of the White House that afternoon. Posters had to be made, speakers had to be chosen, but in this moment, the focus was learning how to present yourself to the media in a way which called others to action and changed hearts and minds.

***

United We Dream is the largest immigrant youth-led community in the United States. It seeks to engage and empower its over 400,000 young adult members to lead campaigns on immigration, LGBTQ, education, health, economic, environmental, and racial justice issues.

In March of 2017, the D.C. area United We Dream chapter was looking for a way to involve younger members in their advocacy efforts, and decided to create a summer program to engage high school and college students. “We wanted to create a space where we could train people on how to become organizers and become first responders to the threats that we were seeing from the current administration,” said Claudia Quiñones, United We Dream’s D.C. area field manager.

There are approximately 20,000 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients currently living in D.C., Maryland, and Virginia, and this number does not account for the undocumented youth who did not qualify for the program.

The inaugural Summer of Dreams was held as a pilot program in 2017 during the first summer of the Trump administration. According to Quiñones, the chapter had been hearing rumors that DACA may be rescinded, but didn’t know when.

It provided an opportunity to expose that summer’s cohort to protesting, and they were able to organize two demonstrations in which thousands came out in support of DACA recipients. The program in D.C. was deemed a success and chapters in California, Texas, New Mexico, Florida, and Tennessee have since begun their own Summer of Dreams programs.

This summer, the D.C. program was held just south of Dupont Circle at United We Dream’s national and D.C. chapter office; their work often intertwines. The students who signed up were mixed in respect to immigration status—undocumented people with and without DACA, recent arrivals in the process of seeking asylum, US-citizen children with undocumented parents, and U.S. citizens who considered themselves allies of the undocumented community. Three mornings a week, anywhere from 15-30 participants attended, a number that fluctuated when students had to babysit last minute or a parent couldn’t make the drive.

During the six-week program, Quiñones, along with Gerson Quinteros, a fellow organizer, and Arisaid Gonzalez Porras (COL ’21), a field fellow, and visitors from other United We Dream departments taught the students about previous social movements and offered concrete tools for mobilizing people to effect change in their own communities. One week’s lessons were focused on the immigrant rights movement, another on organizing in the LGBTQ and Native American communities, and the next the history of organizing in the African American community from the Civil Rights movement through current day efforts to end police brutality. One morning the students constructed an ofrenda, or an altar, in memory of black men and women who had died at the hands of the police, combining a Mexican Dia de Los Muertos tradition with the lessons they were learning.

Gonzalez Porras emphasized the necessary role of the history curriculum alongside the more practical lessons. “In order for people to understand the importance of organizing and campaigning, they first need to

understand the history and acknowledge all the work done before us.”

She added that the Summer of Dreams program taught a perspective on history different from that most students encounter at school and hoped the program would shed light on parts of American history often overlooked.

“They’re not taught through the lens of Native Americans or the LGBTQ [community]. A lot of that is wiped out from their history books,” Gonzalez Porras said. “We’ve been teaching them about slavery. They got to learn that Abraham Lincoln’s first motive was not to free the slaves.”

Gonzalez Porras became involved with Summer of Dreams through her previous work with United We Dream. During her first year at Georgetown, a student already involved with the organization brought her to one of the group’s events. “I volunteer with them a lot during the school year so any time they have a rally or protest I’m always there. Finish a class I go, before a class I go, during exams I go,” she said.

In addition to more insight into U.S. history, students were given concrete tools to push for change in their communities and at their schools. One workshop focused on organizing, the process of mobilizing a community to fight for their dignity and rights. Another touched on campaigns, movements which arise as a community realizes there is a common issue affecting all of its members. Some of United We Dream’s national advocacy team visited to tell the students about lobbying on Capitol Hill. On an outing to Columbia Heights, the students practiced the canvassing skills they’d learned, knocking on doors and talking to residents about what to do if ICE comes to your home or workplace.

Gonzalez Porras said that the Summer of Dreams program aims to empower students to become leaders in their communities. “A lot of them have the leadership capabilities, they just don’t know it.”

Quiñones said she has seen many of the participants grow and gain a sense of confidence as the summer has progressed. “I see many youth come in being shy, not knowing about their rights, not knowing what race truly means in this country and they leave knowing that they want to do more for it, for their community, wanting to educate their peers, wanting to take action.”

Mikaela Pozo lights up whenever she is given the opportunity to talk about immigration rights and advocacy.

“The fact that I am undocumented, it just makes sense for me to advocate for myself and my community,” Pozo said. “One of the things that I’m really passionate about is education equity because you could talk about a lot of things with that: affordable housing, educational resources, diversity.”

Pozo said that the skills she has learned at Summer of Dreams could help her start an organization to address educational equity issues within the DMV area that she feels affect not just undocumented students, but all students of color. “How to organize campaigns, research the issue, find solutions, figuring out the power structure and then figuring out the target based on that power structure and then figuring out the tactics, I feel like all of that is very valuable.”

For Mauricio Angel, a DACA recipient and the president of an immigrant rights advocacy club at Montgomery College, becoming better equipped to organize at his college and in the wider Montgomery County area is only one of the elements he loves about being a Summer of Dreams participant. The sense of community he gained with the other participants was also a valuable part of the summer.

“I’m an immigrant myself and I think what happens a lot is we often feel alone,” Angel said. “We feel like everything is happening and it’s the world against us. But I think coming into a space where we see others who are directly affected by the same issue and finding a sense of community, we all feel comfortable in the space.”

Quiñones emphasized the importance of creating a space where participants feel comfortable discussing their immigration status.

“Many times youth are ashamed, afraid, they hide their status,” Quinones said. “When they see other people that are comfortable sharing their stories, it’s just a different feeling and creates a different space for them where they can truly be who they are without having to hide their identity.”

She said this fear can also lead to self-doubt which prevents undocumented youth from applying to college, scholarships, and internships, and the program aimed to counteract these feelings. “Part of the work that we did was empower them to not be afraid and to actually take those opportunities to apply for their dream schools, for their dream jobs.”

But the discussion this morning was about the importance of sharing your story, and was the second of two training by United We Dream’s communications team on this topic. For undocumented immigrants, sharing stories is a way to add their voices to the conversation around immigration, Quiñones said.

“We often hear on the news that immigrants are bad, and when we take over our stories, we are no longer giving the power to those that do not want us to be here.” Quiñones said. “Through sharing our stories, we create a collective power that it is impossible to destroy.”

Stories also have the personal value of affirming one’s value, Gonzalez Porras said. “When undocumented people share their story it’s like, ‘I’m a person, I’m a human being,’ and that I think gets taken away bit by bit with things that you hear in the media or politics and you feel like you shouldn’t be here, you don’t belong.”

Pozo came to the United States from Bolivia with her mother when she was seven years old. She said that the media demonizes immigrants, and that she hopes to help others recognize the complexities of the issue through her advocacy and sharing her personal experience. “Although technically it is a crime to come here illegally, it kind of diminishes the reasons that caused that,” Pozo said. “I didn’t come here because I wanted to commit a crime.” She said that criminalizing undocumented immigrants devalues the pressures that cause them to leave their home countries in the first place.

***

“Undocumented, Unafraid,” the students chanted in English. “¡Sin Papeles, Sin Miedo!” they echoed in Spanish.

As 12 o’clock drew near, everyone was occupied with preparations for the protest. Gathered in the center of the room, the students practiced chanting and holding their posters. The communications team had explained it was important to present yourself to the cameras standing up straight without shifting your feet too much.

“When we do the chants they don’t feel as energetic because we’re stuck in the same room,” Gonzalez Porras said. “But when you’re outside, we’re facing Trump. He can hear us, and you’re going to let all that go into the chants.”

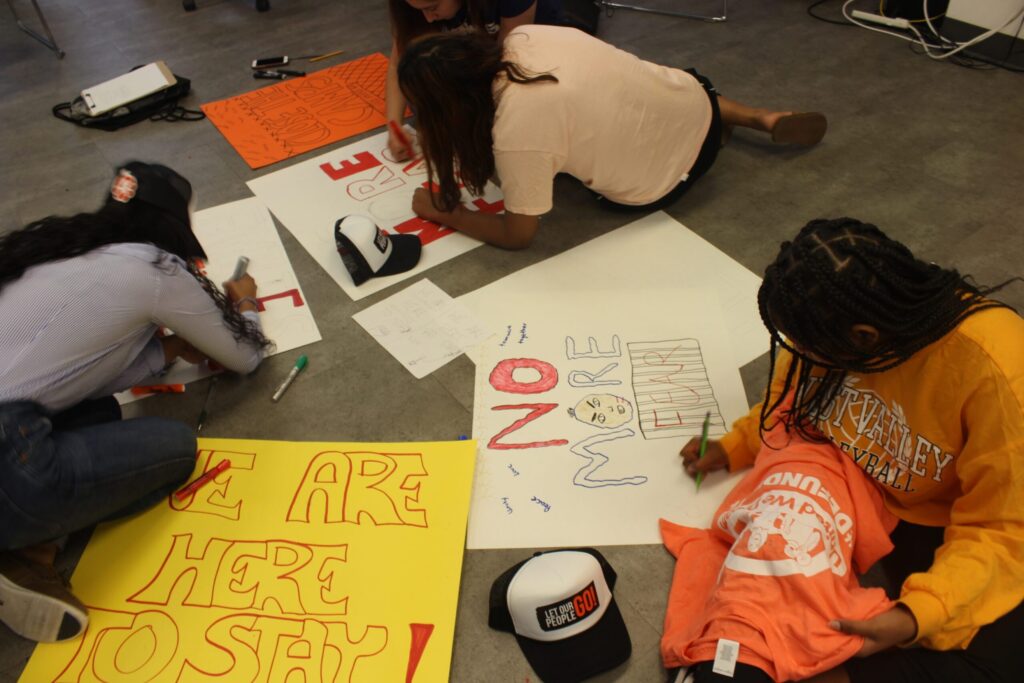

One team was gathered in the corner coming up with the rallying cries they would call out as the group walked toward the White House. Another was in the opposite corner illustrating posters with “We Are Here to Stay” and “No More Fear.”

Bruna Bouhid-Sollod, national communications manager at United We Dream, circled the room asking participants if they would be interested in speaking at the demonstration and might be comfortable telling their story.

Pozo volunteered.

This wouldn’t be the first time she came out as undocumented. She said the first time was difficult and emotional because she didn’t know how people would react and how to process what she had gone through, but that being open about her immigration status has lifted a weight from her shoulders.

“I think storytelling in general is such a powerful tool because it humanizes a very broad issue,” Pozo said. “I think the more I share my story, the easier it is to come to terms with my identity and no longer feel ashamed for being a lot of the things that I am. It’s kind of therapeutic, but also it helps empower me and maybe my community.”

Quiñones passed out United We Dream shirts and hats. Everyone took a moment to use the bathroom. Then it was time to go to the White House.

“Who are we?” the students chanted as they walked through Lafayette Square, “United We Dream!” Passersby voiced their support and pulled out their phones to record. As the White House came into view, a motivational cheer rose from the group. Angel, to start the speeches, told the crowd that had gathered about the 680 immigrant families that had been separated by deportation agencies the previous day. Cameramen from local television stations that had appeared captured the moment. The students and future organizers stood confidently, posters held high and feet planted. Then it was Pozo’s turn to speak.