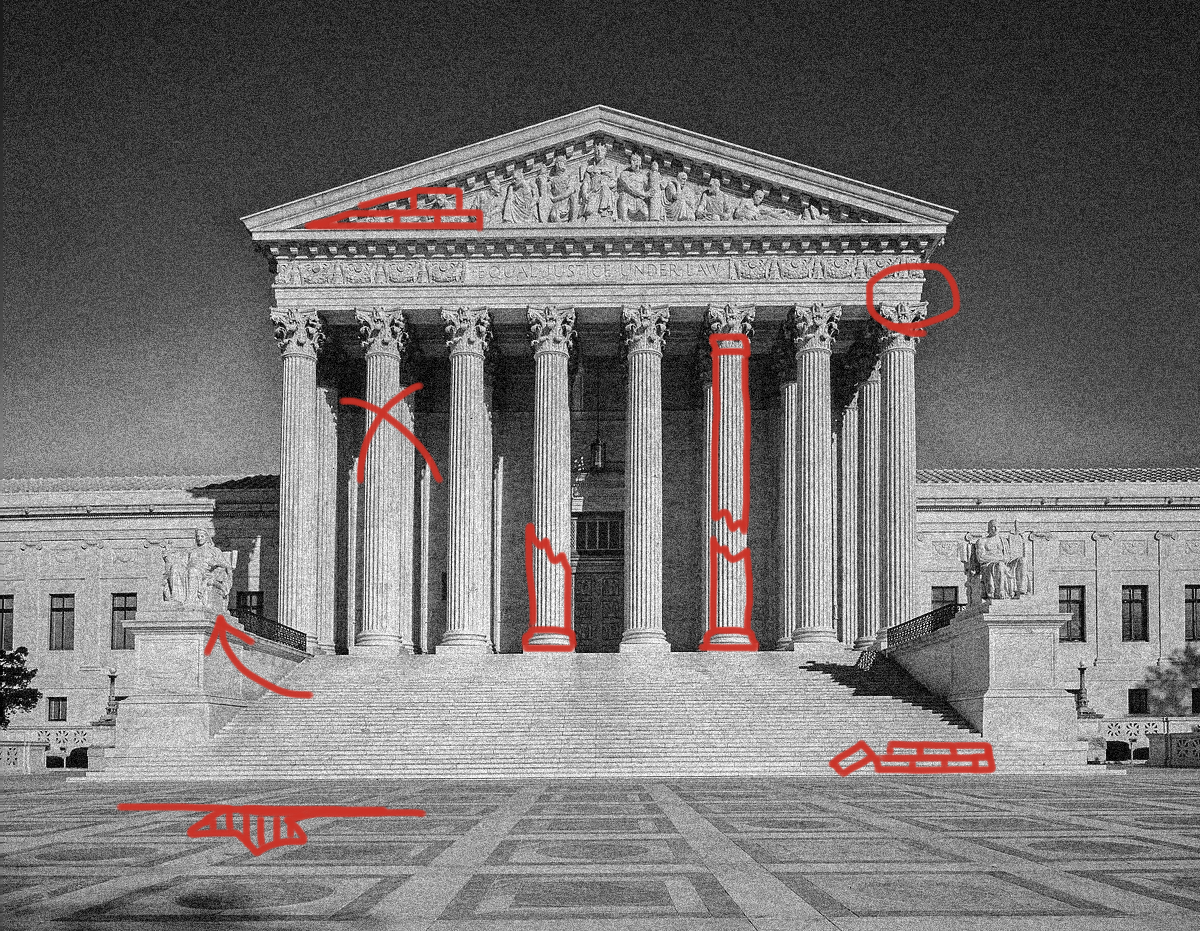

The only solution to a broken system is change. When it comes to the Supreme Court, as evidenced by the rancorous disputes accompanying every seat vacancy, something has clearly gone wrong. The process of filling open seats is riddled with chance, vitriol, obfuscation, and the worst instincts of our political parties. And so the Supreme Court must change if it hopes to remain a viable part of our democracy. Term limits for justices are the way that reform should begin—and legislators should not be afraid to go beyond.

The United States has lost a giant with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The justice’s death closes an era of trailblazing liberal jurisprudence, and with her, the country loses a cultural icon for women and all people who support gender equality and social justice. Though known in recent years for her righteous, fiery dissents against the Court’s conservative majority, Ginsburg’s legacy will no doubt be defined by her greatest victory—arguing before an all-male Supreme Court, one which she had not yet joined, that gender-based discrimination was in violation of the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection under the law.

Unfortunately, Ginsburg’s death also coincides with one of the most tumultuous periods for the Court in recent decades. Calls of hypocrisy have swarmed the Senate Republican Conference, which, with weeks until Election Day, has moved at lightning speed to confirm President Trump’s nominee, Amy Coney Barrett—even while COVID-19 relief bills flounder in the chamber. Meanwhile, frustration with the GOP’s strategies has moved some on the Democratic side to float court packing as a potential solution to their political woes.

Barrett’s nomination marks an inflection point for the Court and is one of its three largest ideological swings since 1953. The new 6-3 conservative majority will have devastating repercussions for issues like reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights. Still, the nomination of a conservative justice by a conservative president is not reason enough for institutional change. Presidents have always had the power to nominate someone who aligns with their views on particular issues. Barrett’s appointment, however, also reflects a longer-term decay of the Supreme Court’s legitimacy.

More and more often over the previous decades, the highest court in the nation has been framed as a political battleground for increasingly dissimilar parties. While historically, appointments were bipartisan affairs—Ginsburg was confirmed in 1993 by an overwhelming 96-3 Senate vote—the Court’s most recent appointments have been some of the most tense and high-profile partisan battles of the past decade.

Though the Court has never been a stranger to politics, Americans today believe the institution should be above partisanship—and justices on either side of the Court agree. The nation values the impartiality of the court system. The theory goes that lifetime appointments remove justices from the influences of politicking, and that requiring a supermajority to confirm an appointment ensures nominees will be moderate and acceptable to the average American. While the supermajority threshold was lowered in 2017, neither it nor the lifetime tenure of a justice achieved the goal of depoliticizing the bench.

In practice, these rules have broken down and caused even greater problems. Lifetime appointments, rather than remove politics from the equation, have instead rested monumental, decades-long seats of political power on a perverse, unpredictable death lottery. The U.S.’s most influential court should not drastically alter its behavior because an 87-year-old woman lost her battle with pancreatic cancer in September as opposed to January. That is not a functional system.

The Court’s justices have also become more ideologically strict over the years. In the past, a president’s party couldn’t necessarily predict the actual ideological leanings of a justice. Conservative presidents like Eisenhower, Ford, and H. W. Bush nominated justices who turned out to join the Court’s liberal bloc once they were seated. This is part of the reason why justice confirmations were bipartisan; a justice’s ideological leanings were less definite, making the vote instead based on their credentials and experience.

This too has changed, largely because of a conservative advocacy group called the Federalist Society. Founded in 1982 in the Reagan Revolution’s wake, the organization is made up of conservative and libertarian lawyers who seek to reshape the federal judiciary to adhere to conservative ideology. It is without a liberal equivalent in terms of its scope and power—each of the five current members of the Supreme Court’s conservative bloc, as well as pending nominee Barrett, are members. An analysis by The New York Times in March found that over 80 percent of President Trump’s appellate court appointees were affiliated with the Federalist Society—twice as many as President George W. Bush. For a judiciary intended to be apolitical, this sort of deliberate partisan stacking is immensely damaging.

While one could argue that the solution to this politicization would be to try and return to a bygone era of bipartisanship, that simply will not happen. That level of cooperation between parties existed in a time when the parties were much more similar. Partisan sorting has all but eliminated the presence of conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans, and polarization is estimated to be at its highest point since before the Civil War. Simply reinstating the filibuster’s supermajority requirement, first ended by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) for cabinet and judicial nominations and then by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) for Supreme Court nominations, will not suddenly fix the problem. The conditions around the Court have changed, and to keep functioning, the Court must change with them.

Foremost among these changes are term limits for Supreme Court appointments. Lifetime appointments have only introduced randomness into the timing of vacancies and benefit no one, incentivizing presidents to choose nominees who are increasingly younger—Amy Coney Barret is only 48 years old—in order to maximize their influence on the Court. This, combined with longer life expectancies, means justice tenures are expected to double over the next century under our current system.

In lieu of lifetime appointments, instating an 18-year term for Supreme Court justices would still give ample time for each of the nine justices to influence the Court’s decisions, while also ensuring that a single nomination does not have an outsized, unaccountable, decades-long impact on American life. By staggering these appointments to once every two years, it would ensure that each election would have an equal, predictable influence on the makeup of the Court.

Even once term limits are implemented, however, Congress must take back its legislative power. One reason why Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination is so troubling to progressives is because a 6-3 conservative majority could easily overturn precedent protecting individual rights. Barrett has advocated for the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision which protects the right to access an abortion. In early October, Justices Thomas and Alito attacked Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 decision legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide.

Congress has never passed these protections into law, leaving their fate up to an ever-changing balance of power on the Court. That inaction must end, and Congress must stop passing the buck to the Court when confronting social issues. Should the Democrats take control of the Senate this November, Congress must immediately move to write these protections into law—even if it means ending the legislative filibuster in the Senate to do so.

Ultimately, though, these changes would exist within a system that is deeply flawed in its own right. President Donald Trump was elected after receiving 2.9 million fewer votes nationwide than Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. Senate Republicans hold a 53-seat majority, despite representing 15 million fewer Americans than the Democratic caucus. Together, led by McConnell, they have reshaped the federal judiciary and appointed a third of the Supreme Court in only four years. Those appointments are now likely to overturn precedents such as Roe, which is supported by 70 percent of Americans, and will hold veto over democratically elected officials for decades.

Term limits may not change all that, but they are a place to start. They are a crucial step for Congress to take if it is serious about returning power to its voters. The Supreme Court, the Constitution, and every aspect of the government is imperfect. They were created by deeply flawed men, living in a world unimaginably removed from the complexities of our own. And right now, they are is showing their age.

We do not have the luxury of sitting idly while the institutions of our government deteriorate before us. The only solution is change.

[…] LGBTQ+ people was unlawful intercourse discrimination. Because the Voice’s Editorial Board pointed out, “Congress should cease passing the buck to the Court docket when confronting social […]

[…] LGBTQ+ people was unlawful intercourse discrimination. Because the Voice’s Editorial Board pointed out, “Congress should cease passing the buck to the Courtroom when confronting social points”—and […]