Pandemics have plagued society for centuries. COVID-19 is certainly not the first. Why is it then that, despite the medical and technological strides, our world is still so susceptible to these disease outbreaks? Perhaps tuberculosis—another infectious respiratory disease that spreads through close human contact—holds the answer.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global pandemic that killed around 1.4 million people last year, making it the leading cause of death by infectious disease. Unfortunately, TB has been historically underfunded relative to its disease burden. Unlike COVID-19, TB is not a new disease; it has been around for thousands of years. But in comparison to similar infectious diseases, such as AIDS and malaria, TB has made less progress in recent years in terms of reducing mortality. Tuberculosis also threatens HIV progress, accounting for one-third of deaths in people living with HIV. Making things worse, TB is considered a re-emerging infectious disease because new drug-resistant strains continue to develop, making it more difficult to treat.

Pandemics exacerbate other pandemics. Low- and middle-income countries, where the majority of TB cases occur, are facing major challenges in combating both TB and COVID-19 outbreaks. Before the pandemic, there had been a 14 percent reduction in the number of TB deaths globally from 2014 to 2019. However, according to the Stop TB Partnership, the pandemic may set back substantial progress made in the fight against TB by at least five to eight years.

TB requires strict adherence to a medication regimen in order for treatment to be effective. Lockdowns and supply chain disruptions are limiting access and adherence to medication, increasing the risk of drug-resistant TB. In India, the detection of new TB cases dropped by 75 percent in the weeks following the start of lockdown. Not only will this increase the number of deaths from TB, but it also threatens global health security by allowing the disease to spread undetected. In a country that only spends around 1 percent of its total GDP on health, the pandemic signals an urgent need to scale up both TB-specific services and health care capacity building in general.

The COVID-19 pandemic shows how interconnected and interdependent our health systems are. A global health problem in one country can easily become one in ours simply because of transnational migration. Indeed, in the U.S., the majority of TB cases are among immigrants. Globalization and migration have advanced society by driving the spread of knowledge, goods, and culture—but it also drives the spread of disease. To reap the benefits of this globalized economy, we must address the challenges that it brings as well.

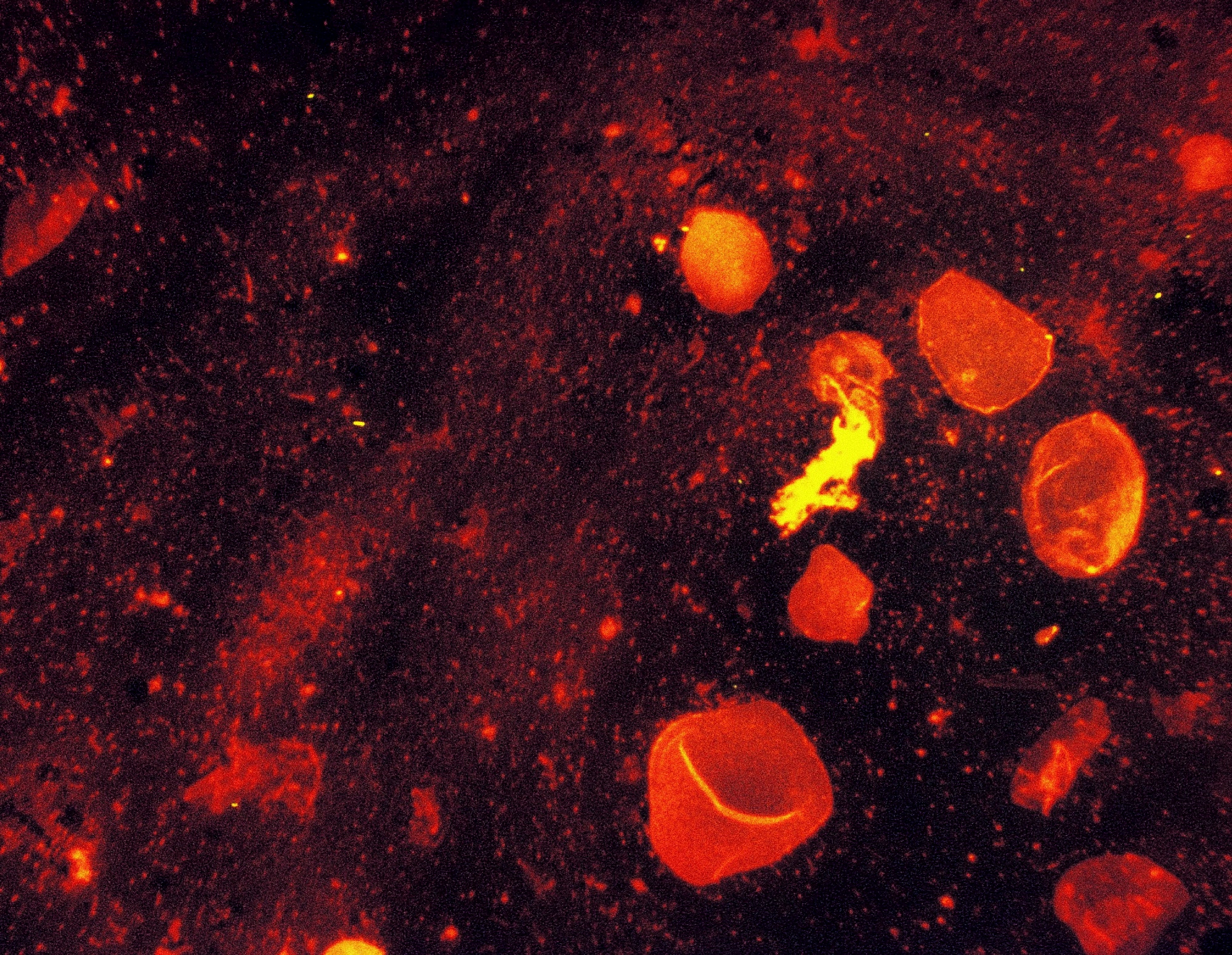

The reason that emerging infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, are so scary is because we don’t know a lot about them. We do not understand the role that children play in spreading this coronavirus. Nor do we understand how long immunity lasts. And despite optimism from public health officials, politicians, and researchers, a universally effective treatment or vaccine still does not exist. TB, on the other hand, is preventable and treatable. The Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine is 70-80 percent effective in preventing children’s tuberculosis. In adults, treating latent TB (before the infection causes disease) is extremely cost-effective. That being said, the less we focus on preventing existing strains of TB, the less effective treatments will become due to drug resistance. While trying to eradicate TB during a global pandemic may seem challenging, treating and managing preventable diseases preserve limited healthcare personnel, hospital beds, and other medical resources for COVID-19.

There are several avenues to improving global health security and all are necessary for pandemic prevention. Strengthening health systems, especially surveillance at the primary care level, needs to be prioritized so that diseases are detected before they become outbreaks. But when the outbreaks already exist, such as TB, then special effort needs to go towards curbing their spread.

Epidemiologists often refer to the “cycle of panic and neglect” during a public health emergency. We tend to focus resources and attention to problems when they occur, but fail to maintain that same support once the immediate crisis is mitigated. For example, U.S. global health funding spiked in 2015 and 2016 during the respective Ebola and Zika virus epidemics and dropped immediately after. But only responding to crises in the moment does not eliminate the disease, resulting in higher economic and human costs. By giving disease programs like TB sufficient funding, we can escape this cycle.

COVID-19 has proven that there has been a severe lack of planning and financing for global health security programs. But TB has been telling us this for years. Warmer temperatures, a growing global population, and urbanization all facilitate the rapid spread of disease, increasing the frequency and intensity of pandemics. TB and other diseases endemic to low-resource areas will continue to lose progress without adequate interventions. As the U.S. Senate approaches the time to pass the foreign aid appropriations bill for fiscal year 2021, we need to pressure the government to step up in its role in promoting global health.

So, when I say that this is a crucial moment for Congress to prioritize global health by supporting increased funding for tuberculosis programs, I don’t mean defunding other global health efforts such as strengthening health systems. I want to highlight the importance of having both disease-specific and more general healthcare spending in a time when everyone is preoccupied with COVID-19.

The TB advocacy community has asked for an increase to $400 million to USAID’s TB account. I’ll be writing to my senators in New Jersey—Sen. Booker and Sen. Menendez—to support $400 million for TB, and I encourage the rest of the Georgetown community to send a brief message to their senators asking them to do the same. As Congress works to pass the appropriations bill, these next few months are critical in supporting the 10 million people who are diagnosed with TB each year. I urge my peers to support this issue that is losing attention when it’s needed the most and join the fight against tuberculosis.

[…] “COVID-19 has proven that there has been a severe lack of planning and financing for global health security programs. But TB has been telling us this for years. Warmer temperatures, a growing global population, and urbanization all facilitate the rapid spread of disease, increasing the frequency and intensity of pandemics. TB and other diseases endemic to low-resource areas will continue to lose progress without adequate interventions. As the U.S. Senate approaches the time to pass the foreign aid appropriations bill for fiscal year 2021, we need to pressure the government to step up in its role in promoting global health. So, when I say that this is a crucial moment for Congress to prioritize global health by supporting increased funding for tuberculosis programs, I don’t mean defunding other global health efforts such as strengthening health systems. I want to highlight the importance of having both disease-specific and more general healthcare spending in a time when everyone is preoccupied with COVID-19.” READ MORE […]