The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed an urgent need for effective communication of complex science in an easy-to-understand way for a general audience—what is known as “science communication.” Facts don’t always speak for themselves, as the scientific and medical communities have learned the hard way over the past year or so by watching COVID-19 misinformation spread faster than the truth. But this phenomenon is not limited to COVID-19 related subjects, and there are lessons we’ve learned about communicating the science of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines that we can apply to move past the pandemic (and hopefully prevent future pandemics).

As a graduate student at Georgetown from 2008 to 2013, I was really interested in the intersection between science and policy. I took science policy classes and advocated for science on Capitol Hill in addition to conducting research studying the effects of stress, trauma, and addiction on the brain. While I left the Hilltop in 2013, I returned to DC in 2017 to intern in Congress, applying my science knowledge for the betterment of mankind. Yet, this was not considered a normal career path by any means. My multifaceted path has been a great asset in the pandemic, and should be more common. I’ve also learned a lot about science communication in the pandemic. How can we apply what we’ve learned in the pandemic to improve science literacy?

For practitioners of science and medicine: Emphasize communication in science curricula

Fast forward to 2020, and suddenly all of the information I had learned as a biomedical science graduate student was indispensable to understanding both the clinical approvals process and the science of COVID-19 vaccines. Yet, it was also not well-known.

By then, I was a freelance science writer, having started my own science writing business, Fancy Comma, LLC just a month before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020. In the early days of the pandemic, I picked up tons of clients who needed to break down the complexities of the science of COVID-19, including social distancing, masking, and resulting supply chain impacts.

It’s clear that public health messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic has fallen flat, leaving many with lingering questions about the COVID-19 vaccine or beliefs that COVID-19 is not dangerous. Sadly, vaccine hesitancy is killing people in the United States; the vast majority of COVID-19 deaths occur in unvaccinated patients. Vaccine hesitancy is one indicator of the fact that science messaging is not getting through to people.

To counteract this, some doctors, such as Peter Hotez of Baylor University, have taken it upon themselves to take time out of seeing patients and conducting research to man the airwaves. Dr. Hotez has called upon experts to embrace science communication to reduce the gatekeeping of scientific knowledge.

Without a scientifically literate populace, doctors and scientists are gatekeepers of crucial medical and scientific information. That is why science communication training should be a foundational part of science education in both undergraduate and graduate science programs. I’ve previously written at length about ways to improve science communication training in the classroom.

For journalists: improve science journalism by hiring writers with science backgrounds.

As a science writer in a pandemic, I counted ICU doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and others navigating this strange new world among my clientele. My colleague, freelance science writer Nidhi Parekh, and I worked together to write a series of blog posts about how the COVID-19 vaccines work starting in July 2020. Our blog posts were published months before the New York Times and other major outlets had vaccine explainers on their sites; By the time those had been published, misinformation had already taken hold. Had mainstream media outlets relied on science-informed journalists before the pandemic, the gap between science and society could have been bridged earlier, leading to greater scientific understanding and, perhaps, greater vaccine uptake.

In a pandemic, we need science journalism that can follow and critically analyze the emerging science. The evolving science of COVID-19 has also made it difficult to communicate best practices to everyday people who don’t have time to keep up with it all. And the introduction of the Delta variant has magnified this problem, prompting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to announce that “the war has changed” when it comes to combating misinformation via public health messaging.

One solution to the problem of incomplete science journalism is by hiring journalists with science backgrounds who have the requisite critical thinking and analytical skills required to report on scientific information.

A large part of why science journalism has failed to dispel misinformation throughout the pandemic is that many people writing about the science of COVID-19 aren’t scientists. Take, for example, a gaffe I blogged about last year in which CNN’s social media team incorrectly defined mRNA in a tweet. This is the type of problem we wouldn’t encounter as often if more journalists had the science backgrounds required to break down this information.

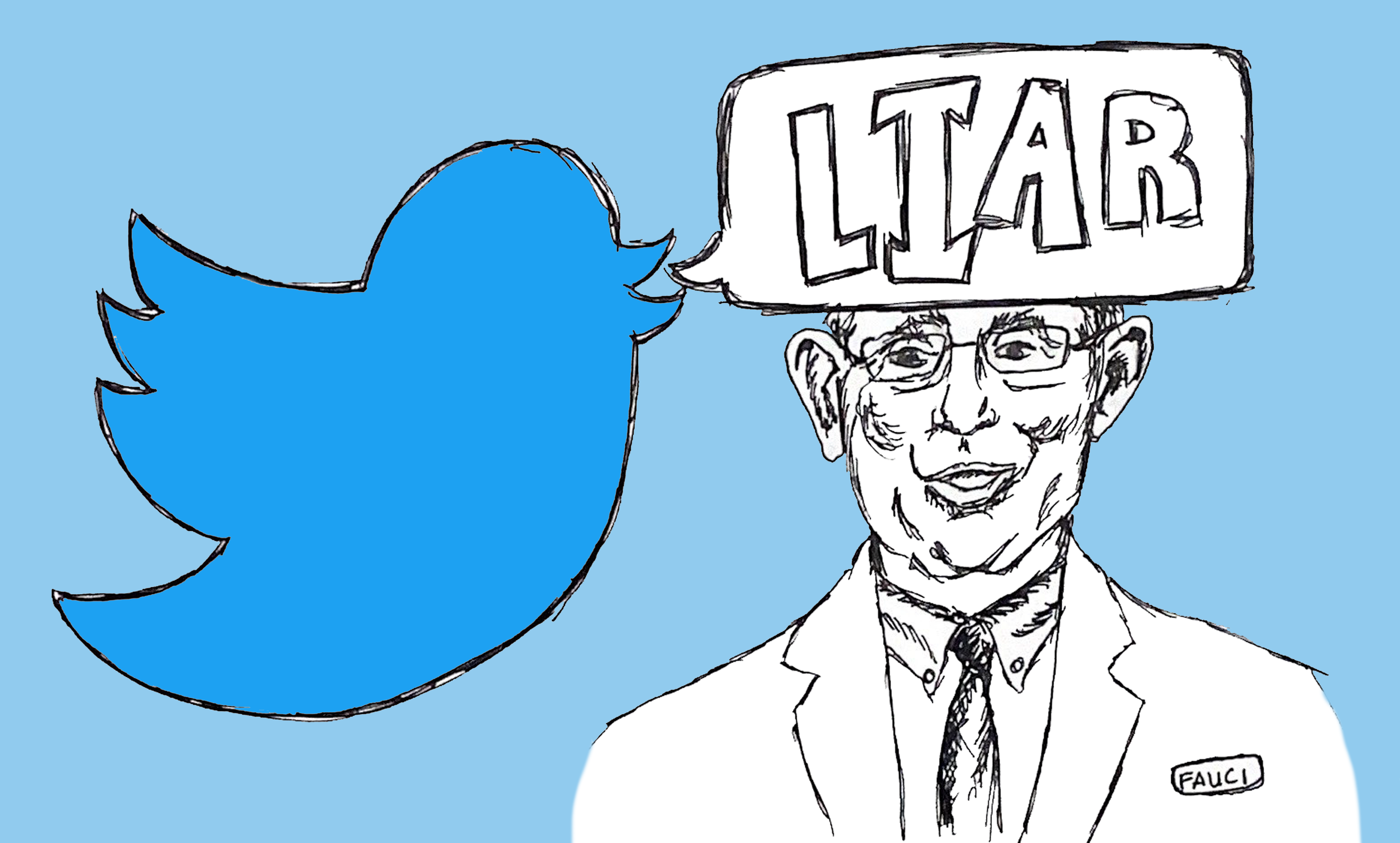

For science communicators and policymakers: Understand the politicization of health messaging to reach a wider audience

A pillar of science communication is knowing your audience. To combat misinformation and boost vaccine uptake through communications, it’s important to know who is vaccine hesitant. Though there is more to the story than mere partisan divides, these divides do play a significant role, and the same science communication approaches used in progressive states are unlikely to be effective in more conservative areas. In an op-ed with Dr. Henry Miller, founder of the FDA Office of Biotechnology, I argue that health messaging surrounding vaccines should speak to and support ideals of “liberty” and “personal responsibility,” ideals likely to resonate politically with many of the Americans who have thus far remained unvaccinated. It’s easy to see how getting a vaccine can help those around you avoid a COVID-19 infection, keeping your community healthy. The most effective vaccine messaging I’ve seen on Twitter didn’t include a single scientific fact, but rather, explained the value of getting a COVID-19 vaccine in everyday terms.

There’s a famous saying in writing and public speaking: “know your audience.” That’s why demographic statistics are useful in understanding vaccine hesitancy. There is a partisan divide in the vaccination effort, though as of April 2021, both parties were over 50% vaccinated, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey. The least vaccinated group was that of 18 to 29 year olds, with only 40% vaccinated, and an additional 24% describing themselves as “wait and see” when it comes to getting the vaccine. Second least vaccinated were rural residents, who were 50% vaccinated, and another 16% saying they would “wait and see” about getting the vaccine. The most recent numbers from KFF, released in early September 2021, show that Black and Hispanic people have the greatest vaccine hesitancy, with 43% and 48% respectively having received at least one vaccine dose. These statistics help health communicators understand who has not gotten vaccinated yet, which can help them target and refine health messaging to boost vaccine uptake in hesitant groups.

For the general public: Take stock of your COVID-19 “ground game”

Meet people where they are, and don’t judge your vaccine hesitant friends—help them overcome their fears about the COVID-19 vaccine. There are many people who remain hesitant to get a COVID-19 vaccine because they have questions about the vaccines, how they were made, what’s in them, and how they work. Rather than dismissing these people as anti-science, it’s important to answer their questions from a non-judgemental space.

Remember the saying, “all politics is local.” The same can be said of the COVID-19 vaccines and overcoming vaccine hesitancy. If you can convince your loved ones to get the COVID-19 vaccine, they will not only largely escape hospitalization due to the virus, but can help others overcome their vaccine hesitancy, too. Think of the COVID-19 “ground game” as you might consider a political campaign in which you go door-to-door talking about the reasons you are voting for a particular candidate.

After all, science communication can play a huge role in ending the pandemic. Lean in to the difficult conversations with your friends and family about the importance of getting vaccinated. If we really want to live in a post-pandemic world, we have to start thinking more locally, and stop thinking in terms of government actions. Our government can only do so much.

What’s more, people in the United States value their personal freedoms, and don’t want to be forced by their government into doing things that they view as violating their liberties. At the same time, there are many people on the fence about the COVID-19 vaccines that are not particularly anti-vaccine: these are the people who can be persuaded to get vaccinated by effective science communication messaging.

If you want to make a difference and help end the pandemic, try to be an ambassador for science and understanding, fighting misinformation and fear. Overcoming vaccine hesitancy through communicating the science of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines to loved ones is a tireless and difficult task, but one that we must take upon ourselves to move past the pandemic. You may get pushback; you may feel like you’re losing friends or family; but when your loved one texts you that they did, in fact, get vaccinated, that makes all the difference in the world in a pandemic.

Taking the time to have a tough conversation with your loved ones is the most grassroots form of science communication. It will go a long way towards keeping them safe and healthy. And, if you can convince them of the benefits of vaccination, there’s a greater chance you’ll get to have conversations with them for years to come.

We can all make a difference in combating COVID-19

As you can see, the science communication challenge in COVID-19 is immense and involves many different stakeholders. To move past the pandemic, we must have an all hands on deck approach to science communication, involving people from all walks of life.