The atmosphere is persistently tense at competitive academic institutions like Georgetown. In the past decade, the rates of depression, anxiety and serious thoughts of suicide have doubled in college students. During the pandemic, students reported significantly lower levels of psychological well-being than before.

“The shorter days, cold weather, cloudy skies, rapidly approaching midterms, and COVID’s continuing spread, among many other things, are all contributing to burnout, depression, and anxiety on campus,” Sara Fairbank (NHS ’24) told the Voice.

Over the course of the pandemic, Georgetown launched new telehealth services, such as HoyaWell, in place of on-campus resources to address mental illness during quarantine, but many students still struggled to find support.

The rapid transition back to campus life this past fall posed unforeseen mental health challenges, and the virtual start of spring semester reignited feelings of loneliness and isolation, mirroring top mental health concerns at the peak of the pandemic.

Campus mental health services are failing to fill this gap. Nationally, 73 percent of students experience some sort of mental health crisis during college, yet only 41.2 percent of students utilize mental health services. At Georgetown, the main provider of mental health services on campus, Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS) struggles to bridge the gap between dependable service and student mistrust.

“Students who have turned to CAPS have felt dismissed or like they were being pushed away. The counselors just refer you to an outside therapist,” one anonymous student said. “Multiple people have expressed concerns, which I agree with, regarding accessibility because not everyone can afford a therapist, and it would be really nice if the university could provide more support.”

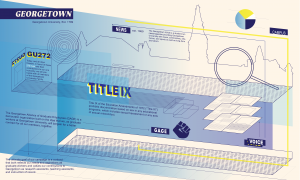

In a recent survey conducted by the Voice to gauge student accessibility and attitudes toward CAPS, while every student participant had heard of CAPS, three-quarters of students learned about it via word of mouth from a friend or peer. Of the services that CAPS offer, students were the most familiar with one-on-one teletherapy (73.9 percent), group teletherapy (60.9 percent) and outside referrals (60.9 percent). Emergency care and psychiatry were less well known, with consultation, workshops and triage services among the least heard of.

Simultaneously, only around 50 percent of students indicated that they have actually used CAPS services to any degree. Students in this subset predominantly used one-on-one teletherapy and psychiatry.

83.4 percent of students indicated that they have either rarely—one to two times per semester—or never utilized the university’s mental health resources. Only 4.2 percent of students use CAPS services on a regular basis.

“The fact that CAPS doesn’t offer long-term counseling isn’t really advertised, so I have heard of many people being disappointed in what they offer,” Fairbank said. “Furthermore, the idea of ‘calling CAPS on someone’ stigmatizes mental illness and mental health crises, and the fear of hospitalization, lack of confidentiality and other consequences discourages people from turning to CAPS in such situations.” CAPS records remain confidential except in cases of child abuse, serious risk to life, or court orders.

“Unfortunately, my friends and I have never heard or experienced good things with CAPS, but I needed more support and didn’t have any other options,” another student told the Voice anonymously. “I think one of the most widespread sentiments about CAPS is that they’re understaffed and overbooked, so students aren’t able to access services when it’s not a ‘crisis’ or sometimes even when it is one.”

These sentiments are rooted in both statistical and anecdotal evidence: 70 percent of respondents described their experiences with CAPS as extremely, very, or somewhat unsatisfactory. Another anonymous student told the Voice that she began seeking out CAPS for mental health care in October 2021, but was not able to have an appointment until two months later. The student expressed frustration with the scheduling system and the lack of guidance she received during the waiting period.

Additionally, there is a knowledge gap for mental health care on campus. In the same sample, only 16.6 percent of students expressed that they are either very or extremely confident in knowing what steps to take if the students themselves or a peer is in need of mental health care.

“Georgetown has a really competitive environment whether it be with academics, or leadership positions, or even competing about how stressed we are. At the same time, it’s so easy for students to experience burnout,” a current student said. “I think the university needs to actually follow through and make mental health resources accessible and intersectional. The campus culture also needs to change and [mental health] needs to be a priority.”

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect CAPS confidentiality policies.