On a typical day in Lafayette Square, the park directly across from the White House, a visitor will inevitably come across tourists, commuters, and musicians. In all likelihood, they’ll come across Philipos Melaku-Bello, too.

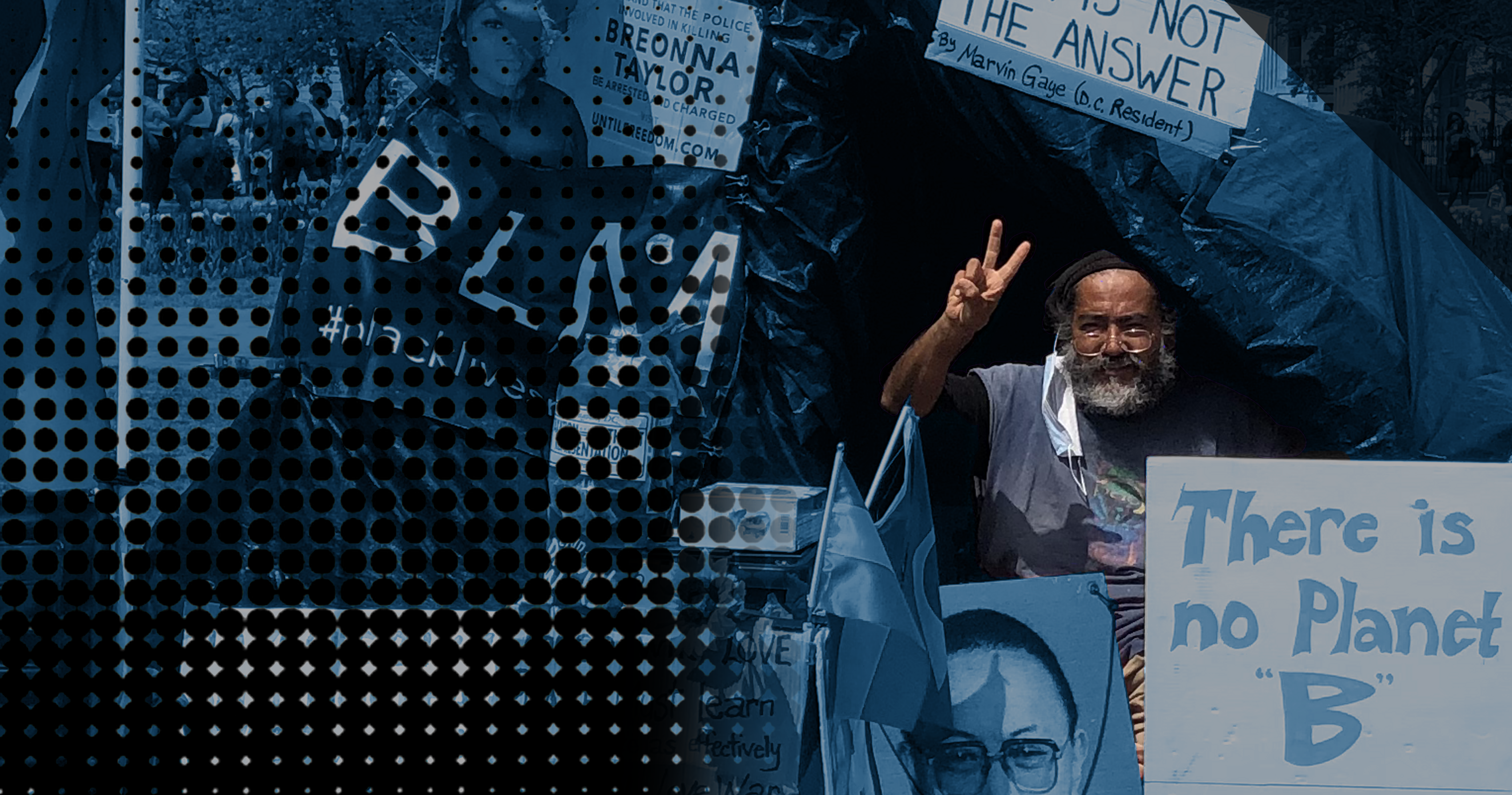

Melaku-Bello and other local activists cooperate to maintain the 24-hour White House Peace Vigil, an anti-war protest site that has protested nearly continuously for 14,930 days (as of publication). Since June 3, 1981, protestors have kept the vigil going through rain and shine (and blizzards and hurricanes). Today, the vigil carries on in the form of a singular black tent surrounded by anti-nuclear war and pro-human rights posters—a display that attracts a global audience.

“I think that this is an effective place where we’re sharing our commentary with more of the public,” Melaku-Bello said. “It’s more effective for when you want world peace—not only peace in your county, or peace in your ’hood.”

The vigil began in 1981 when William Thomas, an anti-war activist who had traveled the world protesting nuclear proliferation, stationed himself in the park with a sign reading, “Wanted: Wisdom and Honesty.” Other activists soon joined him, including Concepción “Connie” Picciotto, Ellen Benjamin (who later became Ellen Thomas when she married William), and, periodically, Melaku-Bello.

At the time, Melaku-Bello, who was born in Brazil, had already lived in Ethiopia, England, South Africa, and in parts of the U.S. He was touring with his band, Anarchistic Youth Brigade, and after several shows were canceled began volunteering his time with Thomas. He’s been protesting ever since. Melaku-Bello’s LinkedIn reflects this involvement— he’s a self-described ‘Professor of Anarchistic and Revolutionary Studies’ at ‘Occupy University’ (a reference to the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement).

Through the ’80s and ’90s, the Thomases and Picciotto were primarily responsible for keeping the vigil running. As the older activists’ health began to deteriorate, however, Melaku-Bello picked up the torch and took on a larger role in maintaining it. Following a brief break after William Thomas’ death in 2009, he returned with the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement.

Today, the demands of the vigil practically make it a full-time job; Melaku-Bello—who resides in Virginia and works in language interpretation—was at the vigil for most of the day last Saturday, as well as from 7:30 a.m. Sunday until 6 a.m. Monday morning.

Melaku-Bello has shifts Monday through Friday from 1 p.m. to 7 p.m., and longer shifts on the weekend. “But that’s a very short week for me,” he said. In the past, he consistently took on daily, 17-hour shifts.

His motivation to endure long, late hours, through violent storms and bitter cold? A love for all humans, regardless of nationality, and a desire to share his message and historical observations with others, he said.

“With liberty and justice for all, there has to be liberty and justice for all,” Melaku-Bello said. “You always have to be ready for the revolution. I want peaceful revolution, but not everybody does, so there’s only one solution: education.”

While the modest White House Peace Vigil does not command the enormous crowds or participation numbers in the way other large-scale D.C. protests tend to, it reflects a more intimate community of care, activist stamina, and a love for humanity.

“I love you,” Melaku-Bello said. “I love the little girl in Bangladesh I’ll never meet. I love the little boy in Botswana I’ll never meet. Human rights violations are a reality on this planet. I want to eradicate them.”

Even with the vigil’s message of universal love, the unconventional movement has not been without its challenges. National Park Service Police, D.C. Police, and park rangers regulate demonstrations within the District and have at times harassed or even destroyed portions of the vigil. In 2013, the vigil was briefly taken down, after the person on shift abandoned their post. Members of the Peace Vigil community quickly returned the vigil to its former state.

Despite the dangers and challenges associated with maintaining a 24-hour protest site, Melaku-Bello is patient in holding profound conversations about history, ideology, and peace with anyone else who stops by. At times, he offers guests folding chairs or invites them into the tent for discussion.

It is the enduring dedication of those within the community of volunteers who keep the protest going. Today, the continuous operation of the vigil requires the efforts of dozens of people—including an activist named Ameena ‘Peaceful’ Washington, another named Luci Murphy, and another activist affectionately referred to as ‘Spawn of Satan,’ along with many others.

After years of tirelessly protesting in front of the president, the community maintaining the vigil is practically family. “She’s my sister,” Melaku-Bello said of Murphy.

While Murphy does not take shifts herself, she has been visiting the vigil since the early ’80s. She often stops by with meals, supplies, and companionship for whoever is on shift. After three decades, she sees the vigil as important and necessary still.

The future of the vigil, however, will require a new generation of support, since the younger Occupy activists have left the movement. Melaku-Bello said that he’s “old as dirt” (legally, he’s 60) and most of the other volunteers are also older. After nearly 21 years on the front lines, the need for the drive and energy of younger activists is felt by Melaku-Bello.

“We’re all aging activists. We’re waiting for your generation. Your generation’s cool—when there is something [to rally behind],” he said, referring to the well-attended—but short-lived—demonstrations that have taken place in D.C. after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “They’ll come out for the rally, but the rally is an hour and a half.”

Michael Beers, who has been supporting the vigil for the last three decades, noted that this dedication will be essential to the future continuation of the protest. “What they really need most are people to stay the nights because technically, we’re not allowed to sleep here. So we’re supposed to stay awake,” he said.

While the original protest featured signs almost exclusively about nuclear war, today’s vigil is adorned with Black Lives Matter posters, anti-death penalty signs, maps of Palestinian loss of land, flowers, flags, and more.

For Beers, the vigil is as essential now as it was the day it began. “This originally started as an anti-nuclear weapons vigil. The core message of anti-nukes is still here and I feel that’s very important,” Beers said. “It’s extremely dangerous right now, with Russia and Ukraine. We’ve got to act strongly as citizens of the world to get rid of these things.”

The vigil’s power comes from its 24/7 commitment to speaking out for peace—no matter where and when. “The peace vigil is the longest living vigil for peace in a country that is constantly at war,” Murphy said. “It’s a constant reminder to people that visit the White House that we need peace.”