As a Portuguese international student, I have spent the past year immersing myself in the coveted all-American college experience.

Of the many observations I’ve cultivated about the United States, one has been particularly surprising: In America, everything is made into partisan politics. Consider the recent school board meetings where ferocious debates about critical race theory have played out along partisan lines, or the FTC’s constant flip-flopping over how strongly to regulate businesses depending on which political party is in power; everything is political.

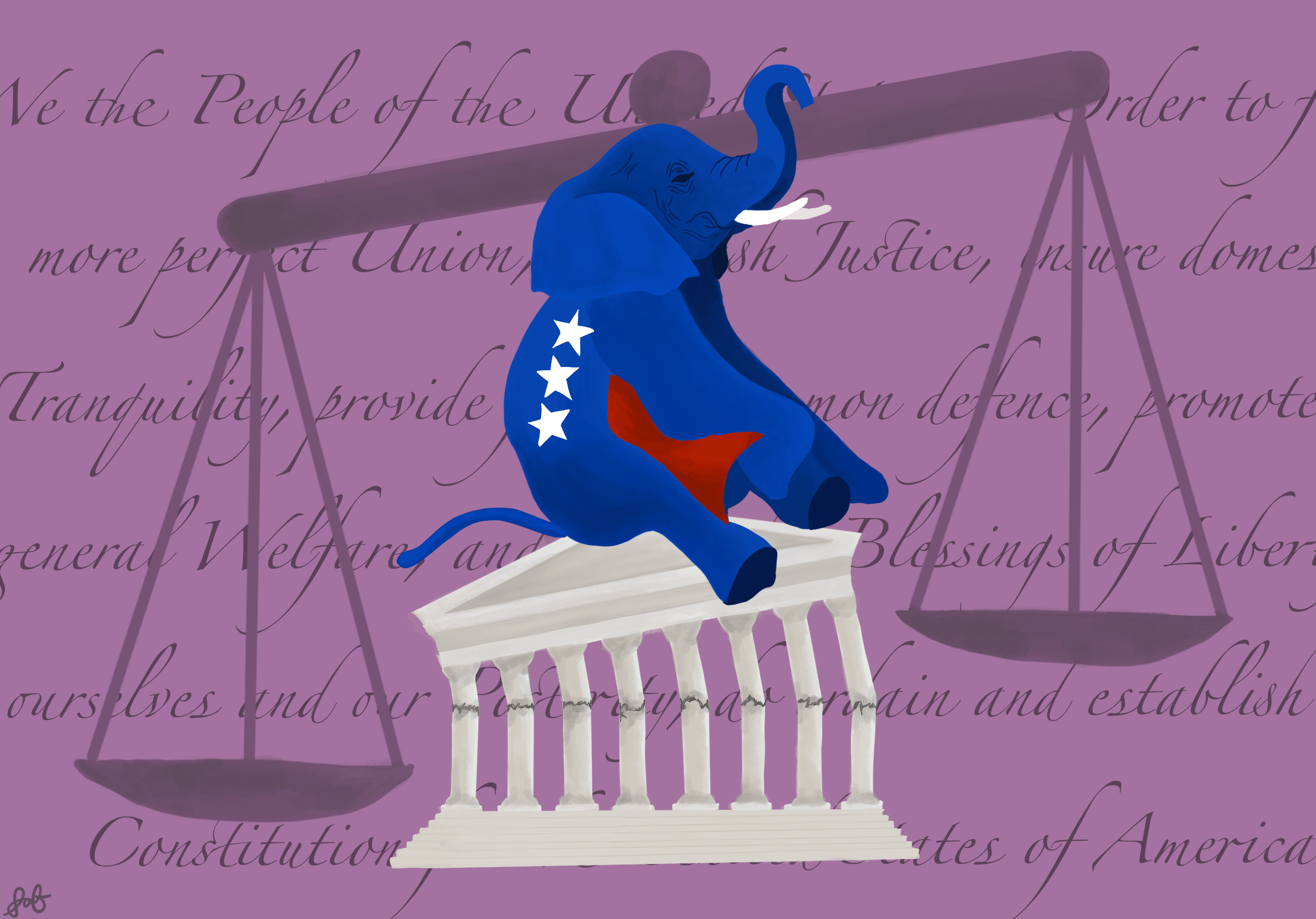

This notion is perhaps best exemplified in the politicization of the United States Supreme Court. For the past few decades, the court’s decades-long nonpartisan reputation has been fractured with rushed appointees and rulings trumping procedure; and with the overturning of Roe v. Wade, its precarious reputation as an apolitical institution has completely shattered.

No matter the legitimacy, or lack thereof, of Roe v. Wade—I find that on such polarizing issues, few are willing to have their minds changed—its overturning was based on partisan opinions and preconceived thoughts, rather than on a true reading of the U.S. Constitution.

First of all, the composition of the Supreme Court is predicated on complicated dynamics: Four out of the five conservatives judges who voted to overturn Roe had controversial nomination processes. Justices Kavanaugh and Thomas faced accusations of sexual assault, Justice Barrett was hurridly confirmed just about a week before Election Day, and Justice Gorsuch was only approved because of a Republican-controlled Senate’s refusal to vote on Merrick Garland.

Republicans have been quickly appointing loyalty-based judges in a game of power—and instead of refusing to fulfill party needs in the name of their prestigious jobs, these judges comply with this game, manipulating the Court’s procedure in their favor.

Justice Alito’s flawed majority opinion relays this: According to him, Roe is invalid because the Constitution does not spell out “abortion,” a right entirely “unknown in American law” until the latter part of the 20th century.

But we must ask: Why is abortion not present in the constitution? Because it was written in 1787, by 55 white men in a time when women couldn’t vote or enter legal professions, let alone have any form of bodily autonomy. I think it’s safe to say that the rights of women and LGBTQ+ people were not high on their agenda.

And yet, that’s the way the U.S. Constitution has always worked: Recognizing that its creation in the 18th century prevents it from covering the breadth of rights that the 21st century American needs. Edmund Randolph, one of the signers of the Constitution, tells us that himself: The goal of the document was to “insert essential principles only, lest the operations of government should be clogged by rendering those provisions permanent and unalterable, which ought to be accommodated to times and events.”

Republicans, however, have long denied this idea with a single principle: originalism. Originalism—a legal ideology championed by late Justice Antonin Scalia—argues the Constitution must be interpreted according to how someone living at the time of its writing would have interpreted it.

When invalidating Roe v. Wade, Judge Alito invoked this philosophy.

But—both in this instance and as a tenet in general—originalism is a disingenuous push of conservative principles disguised as a legal practice. It allows conservatives to deny the expansions of rights under the pretext of faithfulness to the text and the rule of law. The line between what is a constitutional philosophy and what is a political philosophy has essentially disappeared—“original” readings of the Constitution seem to nearly always result in conservatives’ preferred policy positions.

The rhetoric in the ruling points unequivocally toward the partiality of Dobbs v. Jackson: The use of terms like “egregiously wrong,” “abortionist,” and “murderess,” and the questioning of why personhood starts at viability shows how the decision reflects a strong partisan opinion against abortion, rather than a non-partisan reading of the constitution—a truly neutral interpretation of the Consititution would not be concerned with whether something is “egregiously wrong,” only whether the Constitution protects it.

Despite Alito’s deferment to the seemingly neutral doctrine of originalism in the Dobbs decision, a number of his previous opinions make it clear that it was the conservative outcome of the case, not any sort of jurisprudential principle, that motivated his decision.

This partisanship comes despite the fact that the law and the Court are intended to be the exact counteractor of politics—the stabilizing forces preventing personal and partisan opinions on both sides of the political spectrum from pushing the extremes to make America too progressive or too conservative.

If the Supreme Court is political, who is protecting the law? As explained in a Georgetown Law article on partisanship, politicizing the Court might give government actors the ability to perform “partisan gerrymandering, racial gerrymandering, restriction of elections laws, and minority voting dilution.” While this hyper-partisanship only seems to be a concern under the current conservative majority, they are setting precedent for future Supreme Court members, allowing progressives to get their own agenda passed once they obtain the Court majority.

As I said, everything in America is drawn by partisan lines. Coming from Portugal, I used to look at the American experience as a fascinating thing: a population who thrived on their differences, disagreeing with each other’s opinions but respecting everyone’s right to have one. The “shining city on the hill,” built on laws, rights, and votes.

Now, I look at America and something feels broken. Almost like it’s going back in time. Over the course of one week, a much needed law to increase gun safety was struck down in the wake of two horrific mass shootings, and millions of young women have fewer reproductive protections than their grandmothers did. Perhaps it was always naive to think of the United States as an example; now, with democracy crumbling, it’s simply absurd.

Where is this new America heading? I’m not sure, but if it keeps going in the same direction, I might have to move back home.