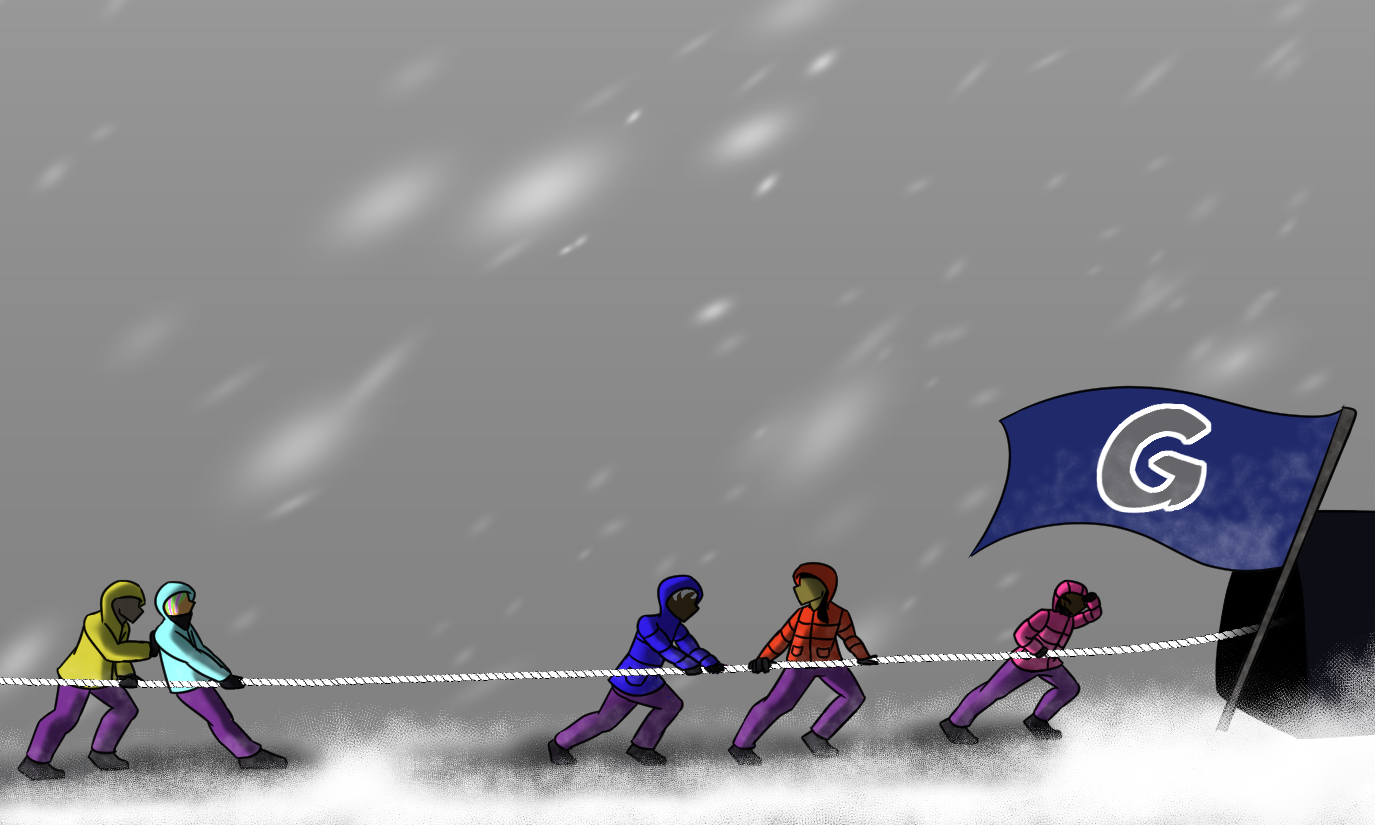

We called NSO “The Blizzard.” It was the weekend the white kids appeared on campus, the event that suddenly shunted us to the margins. From then on, we—the 20 new students in Young Leaders in Education About Diversity (YLEAD), Georgetown’s pre-orientation program for new students passionate about “diversity and social justice”—would feel our marginalized identities in everything we did. We’d feel them in every room we walked into, every person we talked to, every small aggression directed our way. The Blizzard was the moment Georgetown stopped letting us exist so much as people and more so as the labels ascribed to us: Black, white, Asian American, Indigenous, Latiné. Queer and non-binary at a Catholic university. Disabled on a highly inaccessible campus.

I didn’t go to most of my New Student Orientation (NSO) programming. It wasn’t for lack of enthusiasm—I’d been dreaming of the brick and cobblestone of Georgetown all summer long. My absence at NSO had more to do with what I learned the week prior in YLEAD. My transition to Georgetown was guided by the program’s peer leaders—eight former YLEAD participants—who framed the end of the program and the beginning of NSO as The Blizzard. In doing so, they primed the other YLEADers and me for an adversarial relationship with the rest of our freshman class before we’d even met them. They wanted to prepare us for what they understood as the reality of Georgetown: the chasm that separated us from everyone else.

Some of what they said about The Blizzard was true. After YLEAD, I felt as though I had been dropped into a completely different Georgetown. I felt passed over by white peers who, although well-meaning, didn’t think they’d have anything in common with me because of what I looked like. A friend of mine said it was like being looked through instead of looked at, as though we didn’t exist with the same substance as the white kids on this campus. I heard horror stories from other dorms—slurs tossed at students of color, casual racism coming from peers and professors, institutional ambivalence to our trauma.

As a result, I felt unmoored as the YLEAD space naturally faded over the semester, and it became painfully clear that Georgetown was a predominantly white institution (PWI). There was no longer a designated, easily accessible space to unpack the racial dynamics I was experiencing at Georgetown, causing me to bottle up my confused emotions or vent to people who weren’t ready for these conversations. All of this made me understand how important the YLEAD space was for me, and how necessary it would be for future students of color. During my sophomore year, I came back to the program as a peer leader, and as a junior I was co-coordinator. YLEAD consistently gave me the language to understand myself and how I fit into the world. It gave me a community of some of the best and brightest people I know. But as a co-coordinator, I was faced with questions about the program that I had never grappled with before.

To start: Who is YLEAD for? The answer seemed obvious: It’s for diverse people. But what does it really mean to be diverse? According to Center for Multicultural Equity and Access (CMEA) leadership, YLEAD was designed by a white man over 20 years ago as a space for all the “diverse” people—those who didn’t fit the wealthy, white, Christian, cis, and hetero boxes—to amass. While the origin of YLEAD demonstrated a desire to include marginalized students in pre-orientation programming, the success of the space depends on more than inclusion. We need to radically and intentionally reimagine what successful affinity spaces should look like, and the conditions must be set by the people they’re made for.

One of the problems of redesigning a space like YLEAD is that the program relies on staff member roles with low retention rates. Low retention isn’t specific to the program, but is a larger issue that has manifested across student-facing centers at Georgetown. One of the reasons there wasn’t a YLEAD for the class of 2026 is that the YLEAD staff supervisor in the CMEA left for a job with better compensation and work/life balance. The CMEA is home to multiple-degree-holding professionals who are underpaid for the kind of work they do, leading to a high turnover rate. This is particularly concerning considering the largely peerless work that the CMEA does on campus for Black, Indigenous, and students of color, which includes advising multiple affinity organizations, creating community spaces, and providing resources. These opportunities are essential, and could be strengthened with a greater investment in staff wellness and support.

The problem of high turnover and staff labor gaps persists in other student-facing centers on campus. Staff turnover in the Center for Student Engagement (CSE), for example, pushed CSE Associate Director Vanice Antrum into advising the Leadership & Beyond pre-orientation program in August, even though this was not her direct responsibility. The CSE role of Director of Orientation, Transition, and Family Engagement—which oversees programming such as NSO, Georgetown Weeks of Welcome, and Parent and Family Weekend—has remained vacant since the last director’s departure a week before NSO. Patrick Ledesma, the new Director of the CSE, advised NSO this year because of that absence, covering the labor gap at the last minute. Student affairs staff genuinely care about supporting students, so they step in to meet labor needs, but Georgetown capitalizes on that spirit of goodwill under the banner of “Hoyas for others.” If Georgetown’s upper administration truly valued its staff members, they would better compensate them not only with higher wages but also with better opportunities for wellness.

Faced with these gaps, students often end up filling labor needs, and they don’t always get the appropriate training to do so. In spaces like YLEAD, student leaders can bring their own unresolved traumas about Georgetown into the pre-orientation space, and may unintentionally project them onto new students. Trauma is an inevitable part of existing as a marginalized student at a predominantly white and wealthy institution, but somewhere along the course of its 22-year run, YLEAD became a reproductive site of student trauma, leading to new students believing they did not belong at Georgetown. I was ashamed to learn later in 2021, when I was coordinator, that many YLEADers were doubting whether they had made the right choice of college. Just as I had in my freshman year, they feared that this institution would not care about our community, and that they would be ostracized from circles of student life because of identities they could not change. Against our best intentions, YLEAD left its first years feeling that they would never be full participants in campus life.

Now, in my senior year, I understand that this narrative of exclusion is far from the truth. Yes, there were ups and downs in the time I’ve had here, moments of catastrophe and trauma that I wish had never happened, but there have also been moments of joy and triumph, moments when I knew this was where I belonged. They happened in unexpected places—in a Harbin double late at night, in the sticky living room of a Burleith townhouse, at the waterfront at sunset on the first day of summer. It took time, but I feel like a part of the Georgetown community in a way YLEAD initially led me to believe that I never would.

But inclusion alone is not enough to help marginalized students feel at home on campus. It isn’t enough to include us in competitive clubs and societies, or to feature us as speakers at commencement and convocation. Marginalized Hoyas—specifically those who identify as Black, Indigenous, and/or people of color—need our own affinity spaces supported and maintained by the university from semester to semester and from year to year.

In spite of the problems with YLEAD’s implementation, it does allow students of color to safely debrief their experiences on campus away from their white peers. Affinity spaces like YLEAD are crucial at PWIs because there are aspects of BIPOC student experiences that can only be shared comfortably with those who carry the same marginality. In navigating power relationships often skewed against us, we need these affinity spaces to make sense of what happens to us, to be affirmed in the ways that these relationships affect us, and to collectively organize both healing and resistance. YLEAD is not the only affinity space on campus; others include the Black House and La Casa Latina, both also operated by the CMEA. In the 2019-2020 school year, there was an Asian American Home on Magis Row, which sought to provide an affinity space for Asian and Asian American-identifying students. That designation on Magis Row, however, was temporary, and there hasn’t been an AA Home since.

Many of the traditions that were strong within BIPOC student circles on campus were disrupted by the pandemic. The loss of student tradition, coupled with the staff turnover intensified by the pandemic, has led to a compounded loss of momentum and navigational knowledge of the institution when it comes to BIPOC student organizing. In order to resist this institutional inertia, we need detailed and accessible documentation of students’ organizing strategy—how they navigated administrative dynamics, built solidarity with staff and faculty, engaged other stakeholders, and so on. New staff members should likewise be briefed on the historical contexts of the roles they step into, so that they will understand the historical needs of students and how best to support them in the present.

The post-pandemic transition bred at least one new effectively designed affinity space: the Cookout. This overnight retreat for Black students was conceived last spring by four Black student leaders: Veronica Williams (COL ’23), Annaelle Lafontant (SFS ’23), Saleema Ibrahim (SFS ’23), and Kwabena Sekyere-Boateng (COL ’23), three of whom are former YLEADers. They designed the Cookout around Black joy and community building, physically removed from the Hilltop at the Calcagnini Contemplative Center. The Cookout’s success is owed to the values of its four co-coordinators, who used their experiences as ESCAPE leaders, pre-orientation organizers, and Black student organization board members to create a space of uplift and radical hope rather than trauma rehashing. Its success is likewise inseparable from its partnership with Campus Ministry and the funding provided by it. That such a space is not only possible but actual, and that it has been achieved with Campus Ministry’s support, reveals which parts of campus Georgetown’s administration values and which it has relegated to the periphery.

Even so, the Cookout is not institutionalized in the same way that other retreats are. It has no official staff program coordinator employed full-time by Campus Ministry, meaning that once the current student coordinators graduate in May, there’s no guarantee that the Cookout will continue. Students have organized countless times for more support of marginalized students, but our efforts can only go so far without the support of the administration and the staff who supervise programs for marginalized students. Affinity spaces like the Cookout and YLEAD are meant to welcome students who represent some of the most vulnerable populations at Georgetown, but without an intentional commitment to the well-being and development of these students and the spaces meant for them, Georgetown is complicit in their marginalization.

We need a complex inclusivity that goes beyond having students of color merely represented in the clubs and organizations around Georgetown. To be a truly welcoming campus that encourages the growth of all of its students, we need to maintain affinity spaces designed by the people they are intended to support. That means the upper administration at Georgetown must fund and systematize these programs so that institutional memory isn’t lost in the transition between student leaders and the staff members who advise them. Only once we’ve established long-standing institutional support for BIPOC student organizations can we imagine a Georgetown that is truly a community in diversity.