Even when his credits didn’t count toward a degree, even when he was staring down a sentence of life plus 60 years for a crime he didn’t commit, Kenneth Bond took as many classes as he could. He tried just about everything offered at Jessup Correctional Institution, from mediation training to science to ethics.

“A lot of professors like to bring ethics courses into prison, understandably,” Bond told me, chuckling.

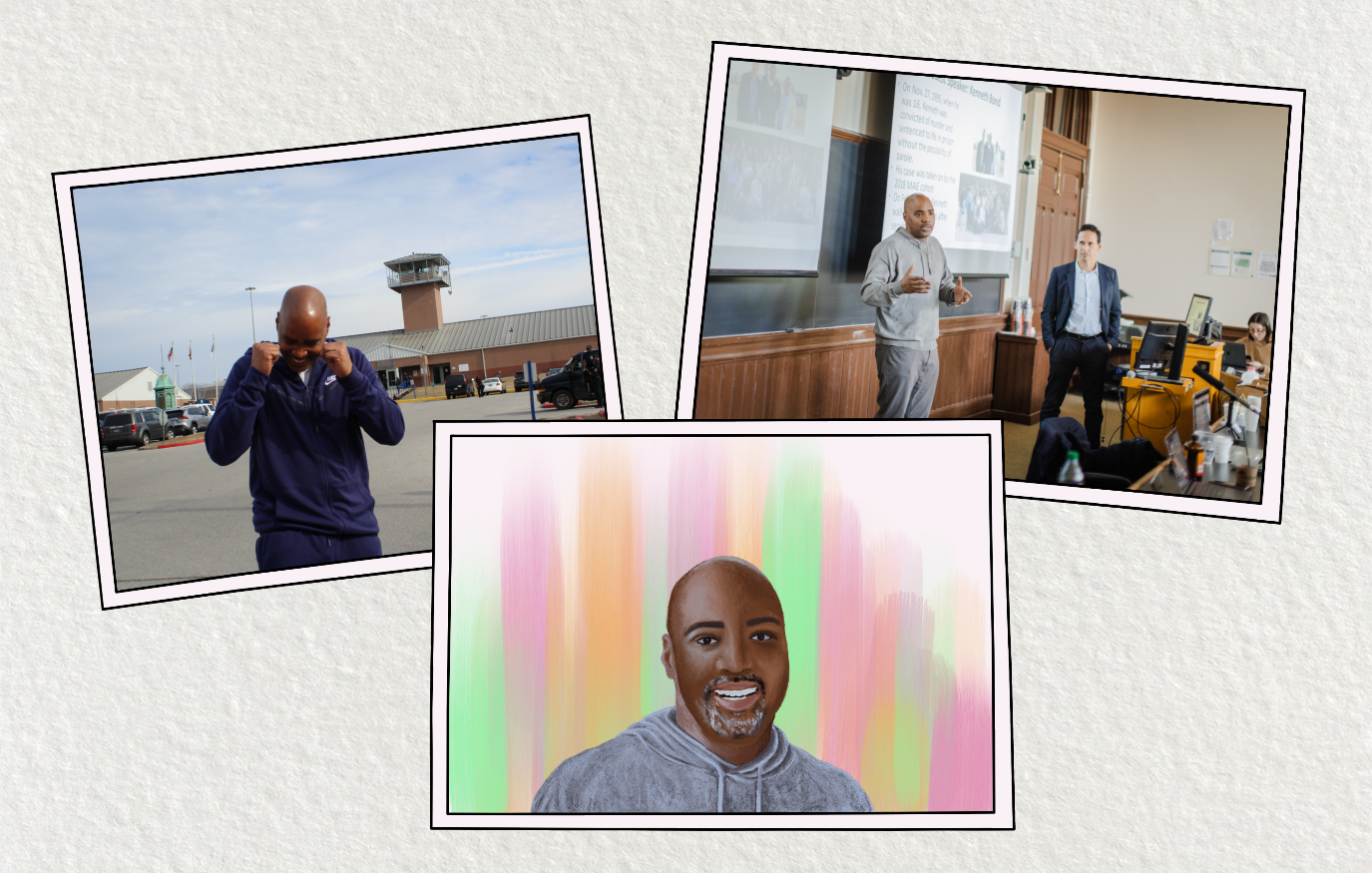

Bond can look back with levity now because he’s no longer in Jessup, where he was held for the majority of his adult life—instead, he’s sitting in a Healy classroom following a day exploring campus with his family. After 27 years, Bond was released from prison last month. He attributes much of the credit for his release to students in Georgetown’s Making an Exoneree (MAE) class, which released his story as a documentary and advocated for his exoneration.

“A lot of things that came out in my case that ultimately, I believe, will prove my innocence and get me exonerated, were things that came out of that program,” Bond said of his experience working with MAE.

Bond was in the initial cohort of subjects when the class was first offered in 2018. Incarcerated people that believe they have a case for wrongful conviction can send their information to Georgetown’s Prisons and Justice Initiative (PJI), which hand-picks cases for the class to tackle. The students then investigate the case and produce a short documentary to prove their subject’s innocence and push for exoneration with an awareness campaign. Bond was the fifth MAE subject to be released from prison since the program started.

Bond didn’t send his case to PJI like most subjects, though—they already had it. PJI director Marc Howard taught a class Bond took in Jessup in 2014, and had since been working on his case as a lawyer—he personally added Bond to the first list of cases.

The students assigned to Bond’s case were Nada Eldaief (SFS ’18), Cassidy Jensen (CAS ’18), and Julia Usiak (CAS ’19). For their documentary, they spoke with Bond, his family and friends, the crucial eyewitness that falsely tied him to the scene of the shooting, and a ballistics expert to analyze evidence used against Bond at trial.

“We actually went to the crime scene, and we got to go to Baltimore a few times and talk to his family members,” Eldaief said. “And we were lucky, too, because we got to actually go into Jessup where Kenneth was at the time, and spend some time talking to him in person. That was really special.”

The students found and documented several critical flaws in the original trial. For one, Bond’s conviction hinged on a lone eyewitness, who later recanted his identification of Bond and said he hadn’t been sure. Additionally, the science that matched the extractor marks on casings from the scene with bullets found in Bond’s home was flimsy even at the time, and would not be permitted in trial today. Nonetheless, the jury convicted Bond, and the judge sentenced him to life plus 60 years in 1997. He was only 16 years old.

“What surprised me the most was how any jury could look at Kenneth’s case and think that, beyond a reasonable doubt, he was guilty of this crime,” Eldaief said.

The students’ documentary captured the attention of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project (MAIP) and Cooley LLP, who joined Howard on Bond’s legal team pro bono. In 2020, they sent Bond’s case to Baltimore City’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU), which reinvestigates old convictions.

“But then a pandemic happened, so everything got shut down, and they weren’t able to work on the case,” Bond said. “So, I waited.”

While Bond was waiting for the CIU to conclude its investigation and reach a finding, Maryland passed the Juvenile Restoration Act (JRA) into law. Bond had earned significant time off through good behavior, including taking classes through the unaccredited lecture series at Jessup and later the University of Baltimore’s Second Chance College Program. That made him a textbook candidate for the JRA, which shortens the sentences of candidates who’ve served at least 20 years for offenses that occurred when they were minors.

“Based off all the things that I accomplished, work history and education and all, they wanted my case to be one of the first cases for the [JRA]. But I decided to wait, I put it off because I was expecting the integrity unit to exonerate me,” Bond said. “The prosecutor of Baltimore City told me to hold on, wait for that. But I couldn’t wait any longer.”

Release via the JRA meant a much longer wait before exoneration—the process of officially clearing his name—but Bond was ready to be free nonetheless. He went forward with the JRA release, and a judge shortened his sentence to 40 years, which dropped to 27 when they factored in time off for good behavior that he’d earned by working and taking classes. Having served 27 years already, Bond left prison on Feb. 9 and was met by his sister, Howard, a number of PJI staff, and current MAE students.

He still has five years on parole and looks forward to the day the CIU officially clears his name. “It shouldn’t be long. This year or next, I should definitely be exonerated,” Bond said. PJI, MIAP, and Cooley are still working to secure it.

But in the meantime, he said, he’s thrilled to be out. He’s finishing his University of Baltimore degree, applying for master’s programs in psychology, and trying to be a mentor to his grandchildren when he’s not at school. Most of all, he’s enjoying his freedom.

“Having that life sentence off you is like removing a thousand-pound weight,” Bond said. “In class we talk about Plato’s Cave. The people in the cave, looking at the wall. Now, you know, to be able to be free and see the actual images, not just the shadows on the wall … that’s what it’s like to be free.”