Content warning: This article includes references to sexual violence.

When Georgetown students gather on the front lawn each Halloween to watch a screening of The Exorcist (1973), it is more than just a seasonally appropriate celebration. Whether they know it or not, it is an ongoing celebration of a film created by and with Hoyas on campus five decades ago.

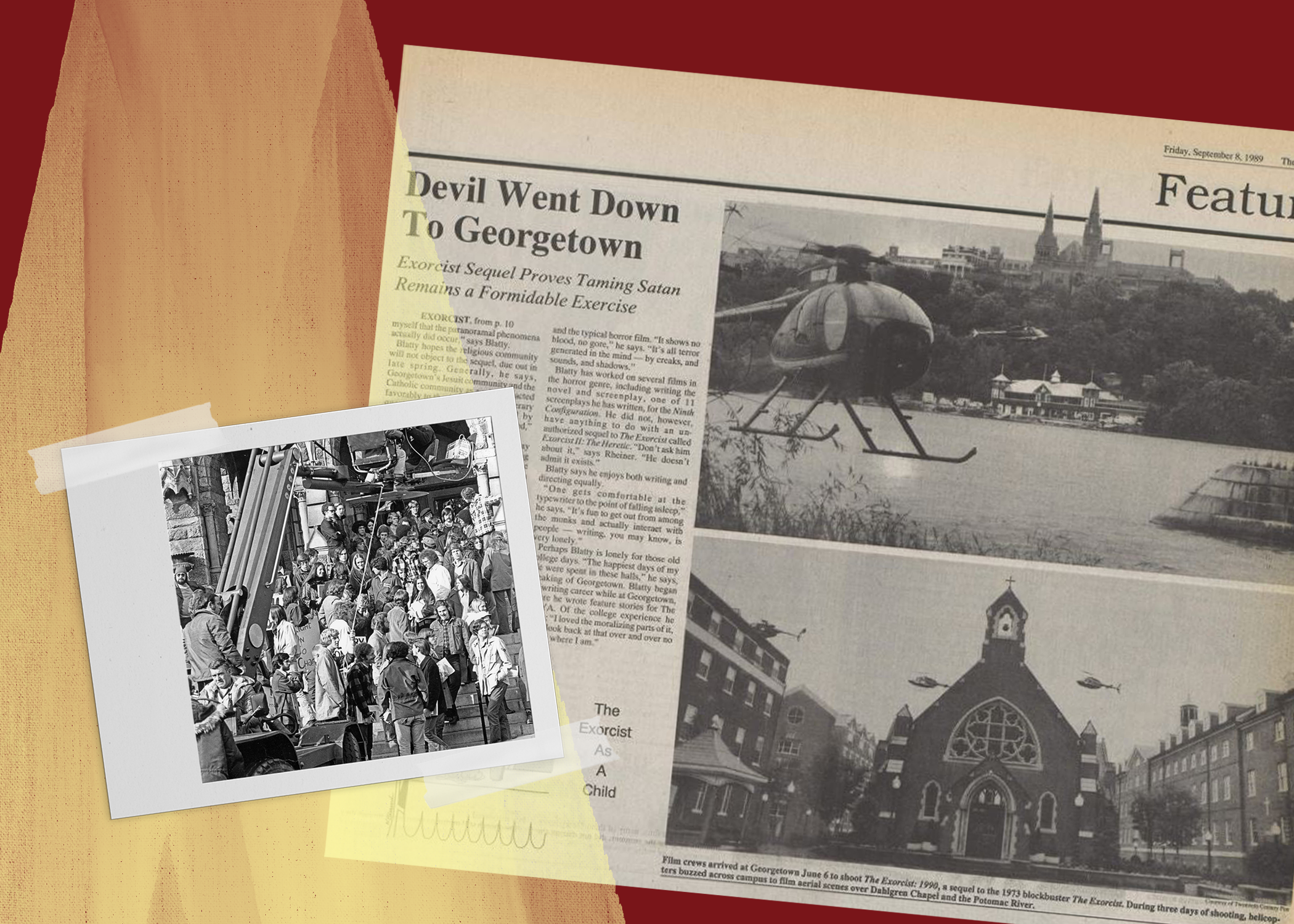

In October and November of 1972, the movie—the first horror film to be nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars—was filmed on and around Georgetown’s campus. Among scenes of evil spirits, possessed children, and heroic priests lie iconic campus locations well-known to undergraduates today, including Dahlgren Chapel, Healy Hall, Kehoe Field, and the now-infamous “Exorcist Steps.”

William Blatty (COL ’50), The Exorcist’s producer, transformed his 1971 novel The Exorcist into the Academy Award-winning screenplay two years later. His son, Michael Blatty (COL ’74), was a junior during the filming.

“[My dad] loved the atmosphere, he loved the people, the professors, and so I think he was just emotionally really attached to the university,” Michael Blatty said. “Maybe he just wanted an excuse to go back and spend time on campus.”

The idea for The Exorcist originated when his father was at Georgetown. “My dad’s told this story a thousand times, but when he was, I think, a junior at Georgetown, he was going through a little bit of a crisis of faith … and he read this story about the boy who was supposedly possessed out in Maryland,” he said.

The idea lay dormant for years and didn’t come to fruition until William Blatty struggled to find work in comedy writing and returned to the idea. “For a long time, he had in mind that one day he’d like to write a nonfiction account of the boy who was supposedly possessed,” Michael Blatty said. His father ultimately published The Exorcist as a fictional retelling, occasionally writing and editing during stays at Georgetown’s Alumni House.

Professor Emeritus Clifford Chieffo was the chair of the Fine Arts department during filming and acted as Georgetown University’s liaison agent—their “contact man”—when the university was approached by Warner Bros. and William Blatty for permission to shoot on campus.

“The president immediately called me because it involved art film. And he said I am going to be responsible for anything that happens on campus, and Warner Bros. cannot step foot on campus without my permission and without me being there,” Chieffo said.

Warner Bros. paid the university over $1,000 a day for filming on their property and enlisted Georgetown community members to be involved in the production. Chieffo recruited more than a dozen of his art students to be among the 550 student extras for filming. The role paid students between $35 to $128 per day to act as background characters, tennis players, and protestors.

“We were famous! No, really, I lucked out,” said Cheryl Amelia Walker (COL ’76), who was a freshman when filming came to campus. “To get there and to come right into this exciting scene just made Georgetown more appealing. And then to be a part of it, you’re like a celebrity. It was a wonderful experience.”

“My dad wanted me to be in the film,” Michael Blatty said. “He gave me a part as an extra in the crowd and he put me up close to where Ellen Burstyn would be with a megaphone so that I could be on camera, even though it was just for about three seconds,” he said.

The first time Michael Blatty met Burstyn, he was in his father’s room at the Marriott Hotel, which hosted much of the cast and crew during the shoot. In tears, she told William Blatty that she heard a hiring agent was taking sexual advantage of some of the women from other universities who wanted to be in the film, saying that if the allegations were true William Blatty had an obligation to fire him.

“It just made a big impression on me because it was 50 years ago. People didn’t talk about that kind of stuff. It was just kind of brushed under the carpet,” Michael Blatty said. “So my dad looked into it and fired the guy.”

Chieffo separately stated that he noticed some crew members acting inappropriately around students; he changed the recruitment location to his office. “I went into total Italian parental mode. These are all my sons and daughters,” he said. One of the extras was Chieffo’s actual toddler daughter, Toby Chieffo-Reidway (COL ’93), the youngest extra in the film. She would go on to earn a minor in theater at Georgetown, citing her experience on set in her application essay.

The production also hired some students for logistical jobs. Members of the Collegiate Club, a now-defunct service club, were hired to redirect traffic away from film sites during shots. “One night they didn’t want headlights in the background, so they wanted somebody to stand a block and a half away from where they were shooting,” said Patrick Early (COL ’74).

The production team also planned for a few Georgetown priests to be in the film. “They went to the Jesuits and most of them said, ‘We don’t want any part of this business,’” Chieffo said. “[But] they got Father [Joseph] Durkin. He blessed the set every day. Blatty wanted him to bless the set.”

“Making the film, I think he sincerely believed that there was a devil, and that the devil might cause trouble on the set, and that it couldn’t hurt to have the set blessed,” Michael Blatty said.

As William Blatty got older, his son said, he became more conservative. The elder Blatty began to feel that Georgetown was straying from its Catholic roots, even starting a petition asking the Vatican to remove the university’s Catholic and Jesuit labels. Michael Blatty said that he thought his father regretted this course of action in the last few years of his life, as Georgetown remained a special place to him even then.

Micheal Blatty also explained how his father’s Catholic background influenced his novel and later screenplay. “He thought that if there were a real case of possession by devils then, by extension, if there were devils then there must be angels. If there were angels, there must be a God. And if there was a God, there’s an afterlife,” he said. “He really wanted to believe that there were authentic cases of possession because, in a way, to him that fortified his belief in God and afterlife.”

Though Director William Friedkin didn’t share the religious motivation that Blatty had, he was still deeply dedicated to the movie. Friedkin was very particular about the film and would reshoot scenes multiple times until they matched his vision.

“He was thinking of this as his masterpiece,” Early said. “On his director’s chair, he had [his Emmy] painted on the back of the chair because he really wanted a second one for The Exorcist.”

Warner Bros. also wanted faculty members to be part of the cast, which Chieffo arranged, but according to Chieffo, “They didn’t like any real faculty members.” Instead, they largely hired Hollywood actors that fit their vision of how the faculty members should have looked for the roles. He estimated that several staff members from the President’s office, along with his office secretary and many more staff members from the second floor of Healy, were in the production.

Despite his reluctance to hire Georgetown faculty, Friedkin, whom Chieffo called a “basketball freak,” hosted a basketball game between the faculty and the crew. However, the director got nervous once he realized that the faculty team had some younger players. So, he allegedly hired a semipro player from Baltimore to be a ringer for the crew.

The film crew, who called themselves the “Exorcists,” played the university faculty members, also known as the “Georgetown Demons,” at McDonough Arena to raise money for scholarships for minority students.

“A Jesuit did all the timing for the Georgetown teams. And we won by—ready for it?—one point. So Friedkin says that the Jesuit cheated!” Chieffo said. “For a week after he refused to talk to me on the set, so a crew member had to intercede.”

Even with crew and faculty working and playing basketball during downtime on set together, the filming of the movie didn’t occur without a fair share of hiccups—so many that cast and crew members said that the set was haunted.

In what is most likely the movie’s most famous scene, the character Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) falls down 75 steps onto M Street, N.W. Making that scene happen required a long process of acquiring the house at the top of the steps, building a fake extension upon the house, and when the extension wasn’t close enough to the stairs, adding an additional fake window overlooking the steps.

Even then, stuntman Chuck Waters faced several difficulties while doing the difficult fall. Production first had to replace the sugar-glass window after the original was too thick and couldn’t be broken. After breaking through the window, “all he had to fall on is a bunch of mattress boxes, cardboard. That’s it,” Chieffo said. “Friedkin said, ‘Alright, you’re done. Now go over and jump down the steps.’ And they changed all the cameras. They did that like three times.” He explained that each step was lined with a half-inch of rubber.

“So the stunt man runs up the ramp, flailing … and misses the steps and lands on the platform,” he said. “So the poor guy gets up and they gave him a glass of water, and Friedkin says, ‘Get over there. Do it again. This time, hit the steps.’”

To film another perspective of the fall, the producers took another calculated risk. “Friedkin takes this $50,000 camera, right? Packs it in styrofoam … turns it on and throws it down the steps. Bouncing, tumbling, doing all the way down,” Chieffo said.

In 2015, Friedkin returned to M Street, N.W. for the dedication of the steps as a D.C. landmark and official tourist attraction by Mayor Muriel Bowser. President John DeGioia attended the ceremony, but because he was not on campus during the filming, Chieffo wrote his speech. When DeGioia mentioned the infamous basketball match, Friedkin stood up, pointed to Chieffe in the audience, and yelled: “You! One point!”

Some alumni credit the film with adding to Georgetown’s prestige and notoriety. “Georgetown has always been a good school, but certain things like that, definitely put it on the map,” Walker said.

“When the movie came out, it refocused a bunch of attention on Georgetown,” Early said. “It brought attention to the university and got more people applying and made it a whole lot more selective.”

For the Blatty family, however, the movie has more significance than just the fame it brought to Georgetown.

“I’m glad that, in some people’s minds, when they read that book, they connect my dad with Georgetown, because Georgetown was so central to who he was and to his life,” Michael Blatty said. “Even in his book, he says at the back, he said he wants to thank Georgetown, to the Jesuits for teaching him to think, and to one of his professors there for teaching him how to write.”

“Content warning: This article includes references to sexual violence.”

That is just so ridiculous.

Also, there are several typos, including the name of one of the article’s main sources who is quoted throughout the piece. Sloppy.

Such a great article! I absolutely loved getting so much of the backstory behind such an iconic movie!

So cool! Such an insightful piece on this significant part of Georgetown history. Great job, Ninabella!