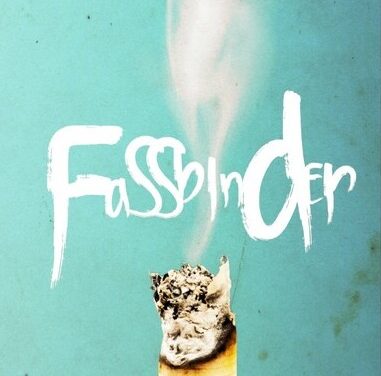

In his latest poetry collection Fassbinder: His Movies, My Poems, writer Drew Pisarra pays heartfelt homage to prolific German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Over the span of 52 poems that have been over a decade in the making, Pisarra—rather than simply rehashing the plots of Fassbinder classics like Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) and Love Is Colder than Death (1969)—captures the sizzling essence of the director’s sizable oeuvre. While a familiarity with Fassbinder certainly enhances the reading experience, Pisarra masterfully ensures a lack of knowledge about this catalog is by no means a barrier to entry. By using Fassbinder’s work as a springboard for his own exploration of the same themes, Pisarra crafts a collection which commemorates the late director’s work while simultaneously continuing the conversation—a collection accessible to die-hard fans and newcomers alike.

Fassbinder helped pioneer the New German Cinema Movement, a period of filmmaking during the sixties and seventies inspired by French New Wave and Italian Neorealist cinema which featured low budgets, experimental visuals, and searing social commentary. Though Fassbinder only lived to the age of 37, he was remarkably prolific, creating over 40 films in the span of 15 years.

In large part, Fassbinder’s fast-paced filmmaking was made possible by his limited number of (usually interior) sets and his affinity for single takes. Still, despite his expedient production style, Fassbinder’s films are anything but sloppily constructed. A proud leftist and openly bisexual man, his films delve into a wide range of topics considered taboo in Germany at the time, including homosexuality and the socio-political reverberations of Nazism. Fassbinder addresses the latter in his Bundesrepublik Deutschland (BRD) trilogy composed of The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979), Lola (1981), and Veronika Voss (1982). Though these films are not narratively intertwined, their explorations of post-World War II life are thematically connected.

Like Fassbinder, Drew Pisarra is a prolific artist. A jack of all trades and master of many, Pisarra has experimented with a variety of different writing styles over the course of his creative career, having penned plays, journalism, short stories, and poetry. His most recent artistic endeavor, Fassbinder: His Movies, My Poems, is the poetic culmination of a decade-long infatuation with the Fassbinder archive.

Though Pisarra’s first Fassbinder film was actually Querelle (1982), his pivotal viewing of The Marriage of Maria Braun from the BRD triptych in 2011 ultimately sparked the poet’s now decades-long fascination with the auteur’s work.

“I wasn’t consumed by his work until there was a Fassbinder Film Festival at Film Forum in New York—which is an arthouse cinema—and I went to see The Marriage of Maria Braun which I loved,” Pisarra said in an interview with The Voice. “I thought it was so hilarious. I remember very specifically the theater was maybe 75% full and I laughed my head off from the beginning but I was the only person laughing in the theater. I was like ‘oh my God, am I misreading this film?’ but ultimately I wasn’t laughing at it—it was just really funny to me because it was very satirical.”

Soon after Pisarra attended this pivotal festival, he began using the filmmaker’s incomparable canon as inspiration for his own writing.

“I talked to this friend of mine who I hadn’t talked to for a long time who was based in Russia and she was coming to New York to do a poetry reading at Cornelia Street cafe which closed a few years ago,” Pisarra said. “There was a blizzard happening, and she contacted me and was like: ‘Hey, do you still write poetry? The poet I was supposed to read with canceled, because they can’t get here because of the blizzard.’ And I was like ‘Yeah!’ and then I thought, ok, I’ve gotta start writing some poems, and I had just seen this film, so then I thought, hey, maybe I could write a poem based on this movie? And then I kept thinking, ok, go back to the Fassbinder Film Festival, see another movie, write another poem, and it just became an obsession.”

In addition to Maria Braun, his self-proclaimed “gateway drug,” Pisarra also cites Fox and His Friends (1975) and Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven (1975) as favorites from Fassbinder.

“I’m a big fan of Fox and His Friends in part because he cast himself in the lead,” Pisarra said. “I don’t think he’s the lead in any of his other films and it’s great. It’s a very tragic film and his character is not the brightest, so I like that he didn’t cast himself in a glamorous role.”

Since Pisarra’s collection follows Fassbinder’s filmography in chronological order, poems corresponding to these back-to-back releases are nestled side-by-side within Fassbinder: His Movies, My Poems. “Mother Kusters Goes to Heaven” is particularly striking in its use of unsettling imagery: “Right around the corner / from the Coney Island Freak Show / there’s a ride they call The Slingshot / or The Dislodged Eye of God.” Just as Frau Küster’s (Brigitte Mira) life is turned upside down in Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven following her husband’s shocking descent into violence at his workplace, the speaker describes a terrifying destabilization which demands a change in perspective: “Free from death and your own story, / you’re now poised to see the world’s curve, / the eternal’s ubiquity and the truth that / you’re far from who you think you are.”

“The Marriage of Maria Braun” is similarly eerie yet rousing in its crisp depiction of a quiet, isolated apocalypse: “The end of the world could be like this…/ a deserted baseball diamond in the park, / not a body in sight, the streetlights on / because that’s what streetlights do. / There’s no reason not to be on.” Again, rather than depicting specific scenes from these films, Pisarra prioritizes the creation of an authentically Fassbinder-esque ambience for the reader.

Pisarra also honors the spirit of Fassbinder by challenging himself to deviate from certain hallmarks of his usual style that are incongruous with the filmmaker’s ideology. For instance, in his two previous poetry collections, Infinity Standing Up (2019) and Periodic Boyfriends (2023), Pisarra examines contemporary queer love through Shakespearean sonnets—a medium historically tailored to tackle amorous themes.

“I would say that love is an obsession of mine as a poet,” Pisarra said. “I just finished teaching a six-week class about the sonnet at Poets House, and I think one of the appeals of the sonnet as a form to me is that it’s a receptacle or a container for expressing love—-even love that’s gone sour and even the feelings that come when you’re rejected in love.”

However, despite Pisarra’s fascination with tender matters of the heart, Fassbinder was highly critical of romance, famously referring to love as “the best, most insidious, most effective instrument of social repression.”

“He made some interesting statements with regards to how insidious he thinks love is and how it’s often used as a coercive tool in capitalism as a way of getting people kind of trapped in a certain role,” Pisarra said. “I feel like his work really opened my mind to expressing different kinds of ideas. I’m so attracted to his discourse about society and gender roles and economics and self-deception—he gave me permission to explore those topics as opposed to just doing what I usually do.”

In hopes of reflecting Fassbinder’s divergent (and arguably jaded) outlook on society both structurally and thematically, Pisarra plays with a variety of different poetic styles that capture his penchant for free-thinking. As evidenced by poems like “Effi Briest” and “The Niklashausen Journey,” this often manifests itself in the form of freeverse. Still, though freeverse reigns supreme within Fassbinder, Pisarra refuses to place his natural proclivity for tried-and-true poetic structures entirely on the backburner: the opening poem “Dear Rainer” is a villanelle; “In a Year of Thirteen Moons” is a sestina; “The Merchant of Four Seasons” is a madrigal. While freeverse is persistently heralded as the poetic form universally emblematic of non-conformity, Pisarra pushes back against the oft-coupled notion that classic structures are inherently stifling. For Pisarra, poetic conventions are hardly constricting—they are liberating, even potentially revolutionary in a modern literary period so determined to abandon them.

“Rhyme, especially at this point in poetry’s history, is an act of rebellion,” Pisarra said. “It is so frowned upon, right? People tend to think of rhymes as cliche. Songs are kind of the last stronghold for rhyme, and even there there is a movement away from rhyme. But, if you are really interested in pushing against the commonplace in poetry, rhyme is a great place to go. The thing about rhyme and these pre-set structures is that I feel like when you have a formal structure that’s kind of a guide for you as a writer, it opens your mind to ideas that you wouldn’t entertain if left to your own devices—especially with rhyme. It’s going to open doors into rooms you hadn’t considered, and if poetry at times is a place for self-discovery, then it’s good to go into rooms that you don’t go into all the time, right?’

Poetry is not the only form of writing in Pisarra’s toolbox. For starters, “Das Kaffeehaus: Director’s Cut” is written in the style of a script, a fitting choice considering Pisarra’s background as a playwright. Likewise, in “Love is Colder Than Death (a recipe for early Fassbinder),” Pisarra substitutes a traditional poem for a list of ingredients and instructions sure to produce a quintessential Fassbinder flick. Drawing upon the interactive style of a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure game, “Theatre in Trance” is perhaps his most fascinating experiment yet. Here, three italicized, instructional stanzas trifurcate two protruding, pennant-shaped text jumbles—the first is about beginnings and the second is about endings. While these triangular sections of text which regurgitate the same handful of words over and over again aren’t all that interesting on their own, the speaker’s stringent commands for the reader regarding how they should navigate the poem offer much food for thought, especially the final stanza which outlines a core message and a subsequent course of action upon the poem’s completion: “(Only from risk rooted in desperation, in which the / artist stands to look like a fool and the soul holds its / invisible ground can poetry re-find a reason for / being. Now move on.)”

Even when Pisarra sticks to the freeverse format most modern poetry fans are familiar with, his writing remains impressive. Metaphors feel fresh but never flowery: in “World on a Wire,” he candidly declares science “the white chocolate / of religions.” The language is clean, but never sterile: “The Niklashausen Journey” muses on “phrases / that I know are supposed to be / the start of novels or the end of plays” such as “‘He had a smile like lemon butter’” and conjures unforgettable images of “fluorescent lights buzz[ing] overhead / like a green God’s vapor trail.” In addition to honoring Fassbinder’s work by mimicking the unique contours of his artistry, Pisarra also honors him through the sheer strength of his prose.

At times, doing right by Fassbinder demanded dauntlessness on Pisarra’s behalf. In addition to challenging the poet style-wise, Fassbinder’s filmography forayed into sensitive subject matter that frequently required Pisarra to step out of his comfort zone in terms of content. For example, Pisarra particularly dreaded writing about the Fassbinder film Jail Bait (1972). As the salacious title suggests, the film depicts an illegal romantic relationship between a fourteen year old girl and a nineteen year old boy. He claims it is “no coincidence” that the poem corresponding with this film was the shortest in the entire collection by a landslide (“An unlawful shock, / you demonically mock / childishness with / shameless flirtations of a lust virginity,” reads the brief yet thought-provoking “Jail Bait” in its entirety). Though grappling with grittier topics necessitated a newfound fearlessness from Pisarra, he ultimately stands by his decision to put his reservations aside and “go there.”

“There’s a second title for that film, and I actually toyed with ‘Oh, I’m just going to go with this other title, because I’m really uncomfortable with ‘Jail Bait,’’ Pisarra said. “But then I thought ‘You’re doing a book on Fassbinder’s movies. You have to honor the spirit of this creator, and that’s what he called it, right? So allow yourself to be uncomfortable and go there, even if it’s for a very short time.’”

In addition to capturing the heart of Fassbinder’s catalog within the poetry itself, Pisarra also managed to incorporate the improvisational, on-the-fly nature of Fassbinder’s single-take style of filmmaking within the press circuit.

“We did an event related to the book at The Tank in New York, and I was like ‘How do I make a poetry reading in the spirit of Fassbinder?’ so I got four performers and told them I wanted them to read some of my poems, but I didn’t tell them which poems. They read through the book, familiarized themselves with the work, and then I had a fishbowl filled with ping pong balls and on each of the balls was a page number related to one of the poems and then I had a stack of cards with their names on them. Then members from the audience would pick a ping pong ball and a card and that was the poem the performer would read. We cycled through the poems that way and it was fun! One of the actors even brought props so she took it to the next level, and as the reading went on we added sound effects behind them so it became more cinematic. Yeah, it was a very fun experiment.”

Ultimately, Pisarra’s goal to commemorate Fassbinder’s richly textured filmography in Fassbinder: His Films, My Poems is a resounding success thanks to his undeniable talent and unwavering dedication to faithful adaptation. For those who were previously unfamiliar with the renowned director before reading this collection, Pisarra’s palpable passion for his work is certain to convince any newcomers to add a few Fassbinder titles to the top of their watchlists.