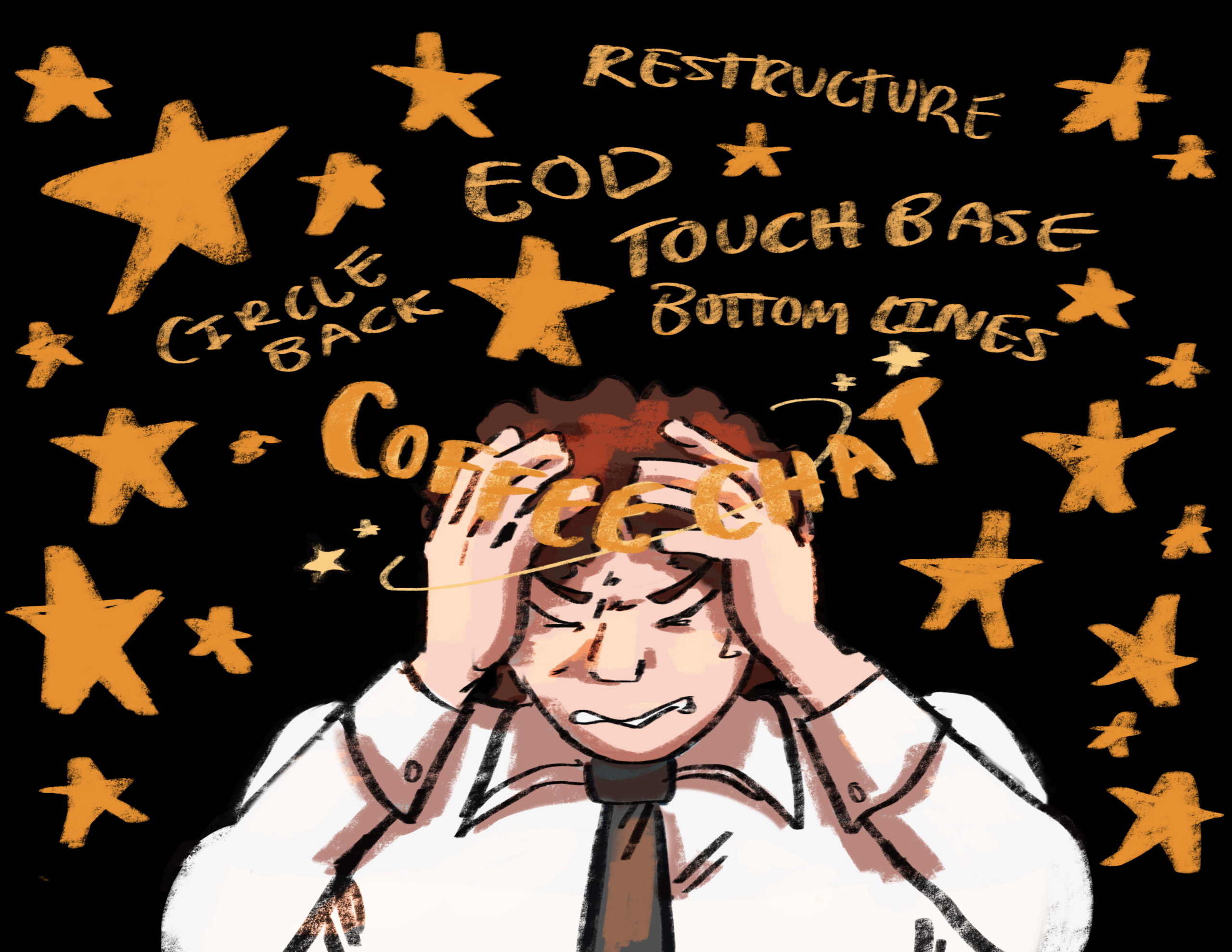

“Can we get this in by EOD” … “let’s coffee chat about this” … “just touching base to see if you have the bandwidth”

We’ve all heard these types of phrases endlessly at Georgetown, especially given the Hilltop’s pervasive corporate culture. In class projects and clubs, we use this language instead of speaking like normal 20-year-olds. In some contexts this makes sense—a consulting club is naturally going to use language created by consultants. However, there are certain spaces that do not need this language. Namely, political organizing.

Yet, this language is used all the time in spaces that should be about connection. As co-president of H*yas for Choice (HFC), Georgetown’s reproductive justice organization, I am by no means immune. Despite being a club that is supposed to bring people together to make change, we still have “action items” that we ask people to “circle back on.” We use corporate language, reinforcing an unnecessary barrier of hierarchy and exclusion of marginalized groups, because the language is cold, distant, and mirrors historically exclusionary systems. It is counterproductive to creating any type of measurable change.

Corporate language dates back to the 1920s, when American factory owners were trying to more efficiently run their businesses. They experimented with environmental factors like lighting and temperature, but realized nothing drastically changed productivity like making employees feel seen. When employees believed that their bosses were paying attention and valuing their work, they got better. Employers began using buzzwords to do just that. The key is that the laborers felt like they were being paid attention to, not that they actually were.

Business jargon evolved from there. In the late 1960s, management in marketing and finance created today’s corporate vernacular to improve efficiency and hide unethical practices. After consulting groups were brought in, phrases like “restructuring,” “letting go,” and “streamlining” were coined to justify firing people. Consulting groups specifically took language intended to make people feel seen and turned it into a way to obfuscate immoral actions. Many of these words were popularized by McKinsey and Company, who employed such phrases while engaging in massive corruption, unethically targeted opioids to high-need communities, and defended fossil fuel companies.

This language enforces hierarchy by creating a barrier between employees and employers, shielding what upper management does from the general labor force. This language hides genuine emotion, interest, and plans behind “paradigm shifts,” “bottom lines,” and “benchmarking,” using impersonal language to the point where no one is actually saying anything.

Speaking in this manner clouds the goals and actions of an organization, in some cases intentionally. In social justice work, while it may not be deliberate, when corporate language is taken outside of the internal group and used for volunteers, advocates, or community members at large, it hides the groups’ true aims. This jargon has become so normalized that no matter an organization’s intention, people use it. However, every time we use language like “deliverables,” “synergy,” and “proactive leadership,” we put up a wall of formality between ourselves and members of our community. We place ourselves in a hierarchical and corporate culture that does not value personal connection. These systems are exactly what advocacy and organizing fights against.

The most effective kind of organizing is relational organizing—using existing relationships to effect change. It is getting your friends together to go protest or texting your parents to sign a petition. And it works. In voter turnout alone, typical organizing measures make someone 0.29% more likely to vote. With relational organizing, that number is 8.3%. To do this work, organizers use much more tangible language. They use personal stories and shared experiences. Rather than “let’s circle back on this,” one may say, “I’ll text you tomorrow.” It’s a small change, but it makes a big impact.

The entire point of organizing is to encourage people to care. Employing impersonal corporate jargon only works against you. There is no way to get someone interested or passionate when you tell them you will “run their ideas up the flagpole.” How are you supposed to change any minds when you don’t say anything real? While the first step is language, the broader issue at hand is actually bringing organizing back to a human level. This language was developed to make people feel seen, but organizing efforts must actually see people.

In fact, using this language isolates you from the very groups you are trying to organize for. When these words are used when speaking to someone who has never been exposed to corporate speech before, it creates further exclusion. Those groups that have been systematically excluded from spaces that teach this sort of language are typically the communities being supported by organizing efforts in the first place.

While there are some circumstances where specialized formal language, such as specific legal jargon, can be helpful, we should, by and large, stop. Organizing only works when people feel connected to you. The entire purpose is to inspire people about your cause enough to make change. That can’t happen when you put up the invisible wall of corporate speech and hide your true message. We need to put the influence of consulting culture aside. Save the buzzwords for another time; now is when we need to talk, care, and connect with others. We need to be real, and that starts with language.