In the era of “participatory” art galleries, the title No Spectators is bold, yet unsurprising. The Renwick Gallery’s current display, running until Sept. 16, takes this name from a slogan of Burning Man, based on two of its tenets: “radical participation” and “radical inclusivity.” The exhibit in and around the Renwick is an attempt to share such practices with the world outside Black Rock City, the utopian civilization both constructed and destroyed within a week by the festival’s denizens who have come to burn the Man.

The burning of the Man did not begin as an exhibition. The secular ritual was born in 1986 when its late founder Larry Harvey and his friend Jerry James gathered a small group to burn a wooden effigy–the Man–a practice that stood for freedom from societal standards through the creation of a world separate from civilization as we know it. Over the course of years and decades, more and more artists have flocked to Nevada’s Black Rock desert annually to build and burn the Man, filling the wasteland with a city of art to destroy it in a comet’s flash, leaving a blank canvas for the next year.

The unfortunate circumstance of reality is that nothing—neither Burning Man nor its gallery echo —can exist as quite the ideal we’d like it to. No Spectators is most successful when it offers commentary on Burning Man, or an analysis of what Burning Man might mean in the context of the world and what the world might mean in the context of Burning Man. When No Spectators attempts to emulate Burning Man, it fails.

As the Renwick Gallery reveals, Burning Man is ripe with irony. Black Rock City is structured to be anti-materialistic, banning monetary sales of anything but coffee and encouraging residents to give freely to one another, yet attendees often spend hundreds or thousands of dollars preparing for and getting to Burning Man. Black Rock City is a utopia disconnected from modern society, but the city and the art within are echoes of, and often responses to, real world issues.

In one of its most lovely displays, the Renwick features a one-third-scale replica of sculptor Marco Cochrane’s 55-foot-tall statue of a twirling dancer, Truth is Beauty, that he debuted at Burning Man in 2013. As quoted in the gallery, his intention was to display the “feminine energy and power that results when women feel free and safe,” a liberating reaction to rampant global sexual assault. Tragically, Burning Man is as much a part of this problem as it is a voice of the resistance: The festival still struggles to impress a culture of consent among participants, facing reports of sexual harassment and rape. Beneath a colossal empowered woman, women who have come to seek freedom remain in danger.

Burning Man’s uncanny development is part of what makes it difficult to translate into a gallery exhibit: It is idealist and escapist and, like most wild things, it does not breed in captivity. The phrase “no spectators” is befitting to a city that literally could not exist without each of its brief citizens taking part in its construction, and so every individual—whether through building, donning avant garde costumes, erecting towering art displays, or taking part in the city’s “radical gifting”— becomes a part of the creation. By comparison, the term is uncomfortable to serve as the title of an art gallery where most viewers “participate” by snapping portraits by the artwork for the ‘gram. But to be fair, Black Rock City, too, has fallen victim to the social media frenzy.

But the art pushes back and demands to live among us, so it spills beyond the gallery’s walls and into the city. Dispersed amid the Golden Triangle neighborhood—D.C.’s cosmopolitan business district, near the Renwick—are six otherworldly installations born from Burning Man and juxtaposed against the painfully real world of American commerce.

In Black Rock City, the installations are connected to the real word in how they echo this its challenges—loss, death, discrimination—but their new placement amidst the capital metropolis has transformed them, as the statues have come to reveal the inspirational power of our mundane experiences. An enormous grizzly bear with fur made from pennies, a pair of six-foot-tall bronze crows in the park, both constructed to symbolize difficult or heart-warming life experiences, each strangely familiar enough to make one question their reality.

And the art speaks, sometimes literally. Mischell Riley’s 20-foot-tall bust of Maya Angelou, Maya’s Mind, invites audiences to stand between her gigantic ears and listen to a recording of Angelou’s “Still I Rise,” part of Riley’s larger project to amplify women’s voices and build their representation in sculpture. It’s an alien artform that shouldn’t feel so strange, if only the world welcomed more of it.

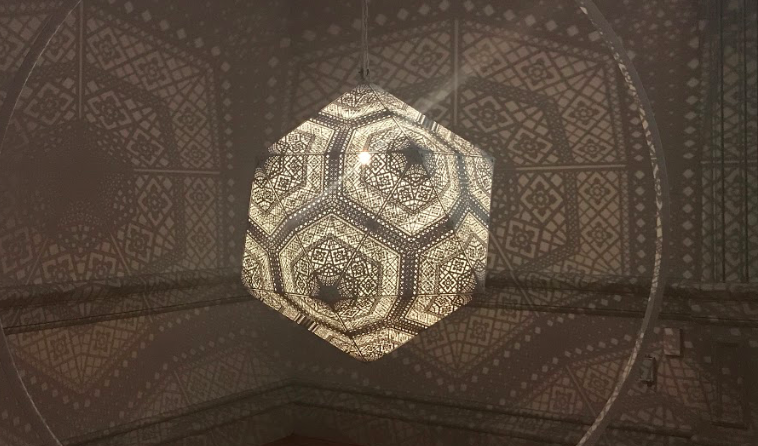

I cannot bring myself to be comfortable with No Spectators. My passions for performance arts and savoring moments and attempting to write about those moments force me to believe that there is something valuable, perhaps magical, in the simple state of the ephemeral being just that: completely temporary. The gallery representation of No Spectators departs dramatically from the ethos with which the art was created and lacks the power to match what Burning Man— or at least the ideal concept of Burning Man—offers to the world. Currently, inside the Renwick, a room has been transformed to a wooden temple designed in the likeness of the sacred temple built every year at Burning Man, but the difference is that this replica temple will remain intact after the temple at Burning Man has been burned to the ground in the cathartic ritual that gives the temple its purpose.

But the art itself is breathtaking, and the art deserves to be seen by the enormous portion of the public that cannot devote the time or money to an extravagant sojourn in the desert. In a room of enormous, luminous, mechanically-animated mushrooms, I watched an elderly woman’s joy Buas the mushroom grew in her presence, and I want to believe that her joy makes the gallery worthwhile.Art is not a design, a structure, or an image, but a living and breathing imprint on a society that gives and takes and becomes art through the exchange between the artist and ideas and the world. Burning Man is an imperfect container of art, as is No Spectators, but each is an artform in itself because each manages to contort the viewer’s mind and perplex attempts to explain it.