When Steve Pisinski (COL ’71) arrived back on campus after the summer of 1968, the country and Georgetown seemed to be at a crossroads. Anti-war protests were engulfing college campuses across America while race riots tore cities apart. Many of Georgetown’s established institutions seemed content to ignore the action, Pisinski thought. From his Ryan Hall dorm room, Pisinski assembled a group that shared his frustration with the university’s apparent apathy to the demands of a changing nation. They searched for a way to reach out to like-minded students and remind the campus that there was a world beyond the front gates. That ambitious endeavor eventually took the name of The Georgetown Voice.

Rev. Raymond Schroth, S.J., a new Jesuit, had just been assigned to Ryan Hall. He and Pisinski became fast friends, and their conversations grew to include more politically engaged but ideologically diverse students.

“It was a small group dissatisfied with the campus paper,” Schroth said of Pisinski and his friends. Pisinski was a staff writer for the campus newspaper, The Hoya, and he was becoming increasingly frustrated by the newspaper’s refusal to cover the country at large. So he and Schroth secured funding from the director of student activities and set out to start their own publication.

Pisinski recruited Martin Yant (SFS ’71) to join the the breakaway paper. It was not a hard sell—Yant fundamentally disagreed with the role that Don Casper (COL ’70), The Hoya’s editor-in-chief at the time, thought campus journalism should play. “He had no use for the anti-war movement,” Yant said. “It was everywhere, and he just wanted to ignore it.”

Yant believed that the anti-war movement and the other issues of the day demanded all students’ attention, especially as movements crept closer to the Hilltop. In the protests following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Yant remembers “standing up on Loyola Hall, on the roof, watching the city burn.”

But while the country was quite literally in flames, the politically charged atmosphere seemed to stop at the front gates. The College only began admitting women in 1969, and the university, approaching its bicentennial, had never had a lay president.

It was not only the administration that was behind the times. Younger students criticized the Yard, the student government, as archaic and ineffective. The freshman class of 1972 refused to elect representatives to the Yard and instead broke away to form their own governing body. Their secession put the university’s historically powerful institutions on notice, especially The Hoya.

“In those days, The Hoya was the preppy paper,” said John Baldoni (COL ’74), an early staff writer and photographer. It promised coverage of on-campus news, but some progressive groups felt they were not given the coverage more established institutions received. The class of 1972, frustrated with its reporting, burned copies of The Hoya in protest.

To the Voice’s founders, it was clear that campus journalism needed a change. Schroth credits Pisinski for turning that desire for change into a reality. “I think it was the charisma of Steve,” he said. “The others wanted to be with him—wanted to be on his paper.”

Many writers from the first days of the Voice agreed that the publication would not have succeeded without Pisinski, who passed away in 2002. Alan Di Sciullo (COL ’72, L ’77), a founding member, recalled that Pisinski had the perfect temperament to be the editor of a publication. “Steve was a straight arrow,” Di Sciullo said. “He was down to earth, not flamboyant. He ran a tight ship.”

Pisinski was strong-willed yet did not take everything seriously, two traits Schroth vividly recalled. “He was very independent minded,” Schroth said. “He even grew a mustache for a while, which is unusual for a freshman. I told him I didn’t like it. He said, ‘I didn’t grow it for you, and I’m not going to not grow it for you.’”

Pisinski’s uncompromising attitude extended to his views on journalism. To him, Casper and The Hoya had failed in their responsibility to promote discussion and bring important issues to the campus’s attention.

In a column for the Voice’s 20th anniversary, Pisinski maintained that the early rivalry between the Voice and The Hoya challenged each publication to improve. “The Voice was organized not as an attempt to replace The Hoya but as an alternative journalism outlet,” he wrote.

The Hoya was trapping the student body in a bubble around Georgetown, Schroth said. “The Hoya never wrote about the outside world, the Vietnam War, the protests. It was like Georgetown was in a different world.”

So, the Voice set out to be something new. “We wanted to start something more dynamic,” Di Sciullo said.

The Hoya’s first mention of the Voice was in its Feb. 13, 1969, issue, which announced the “new campus monthly organized by students.” The article listed the leaders, including Pisinski and Schroth, and laid out the direction the new paper promised to take. “It is a safe assumption that the Voice will attempt to take the underground route, staking out a more radical position than The Hoya,” the article read.

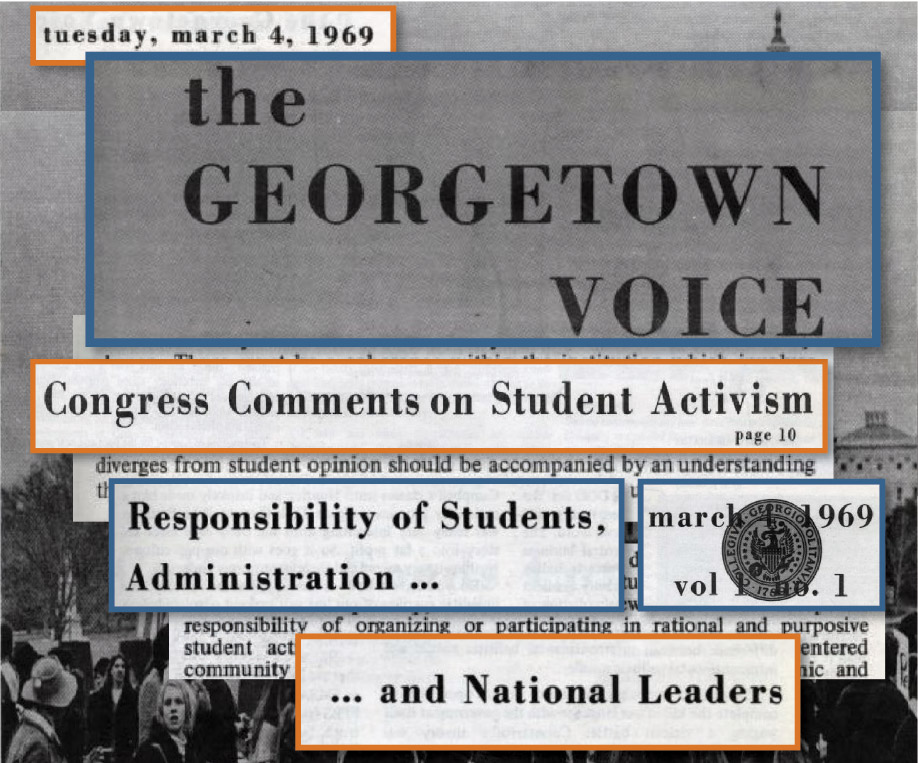

The hard work of Pisinski, Schroth, and many writers culminated on March 4, 1969, when the Voice published its inaugural issue. In their debut editorial, the editors declared their intentions. “We promise to present and analyze national and local issues of concern to the student, whose concern should spread beyond campus,” the editorial read. “With the first issue of The Georgetown Voice, we present a new style of journalism to the University.”

From its inception, the Voice aimed to hold institutions accountable. In the second editorial of the inaugural issue, they demanded that the administration improve its responses to the changing needs of the students. “The university can continue to exist only if honest criticism is followed by change.”

The other articles in the first issue were equally ambitious. Regarding on campus news, they covered the “ineffective student government” and the increased inclusion of women at Georgetown. Beyond the front gates, Voice reporters asked congressmen about student activism and gave Led Zeppelin’s first album a lukewarm review.

This opening edition was well received on campus. Letters to the editor published in the second issue offered glowing reviews, congratulations, and good luck for the future. Rick Newcombe (COL ’72) remembers that the Voice’s debut set campus abuzz. “It was pretty electric,” he said. “Everybody wanted to read it.”

That momentum, however, was hard to sustain. Maintaining a publication was difficult work, and finding enough material to fill the pages threatened to be a problem. In their fourth issue, the Voice did not receive a single opinion submission. “A newspaper has no way of knowing if it is meeting its obligations to the community if the community refuses to comment on the paper’s performance,” the editorial board wrote. “Damn us or praise us. But write us!”

Funding also became an issue. No one knows for sure why Robert Dixon, the director of student activities, was initially willing to fund a second student newspaper. Regardless, he was indicted for embezzling from the university soon after, endangering the money he had allotted for the foundling Voice. “The Voice was almost dead in the late spring of 1970,” Yant said. However, its leaders managed to hold on to their funding as they tried to establish the Voice as more than a flash in the pan.

Pisinski, Di Sciullo, and the other writers set out to cover stories that other publications had decided were beyond their scope.

“The Voice obviously has contributed a forum for airing issues, an outlet for student opinion, and a point of view that, if not always controversial, invited thinking and discussion,” Pisinski wrote in his 20th anniversary column. “As soon as the Voice, or any journal for that matter, ceases to make such contributions, it should cease publication.”

In the months after its first editions, the Voice tried to expand the scope of its coverage. During Yant’s tenure as managing editor, this meant covering a range of perspectives as well as issues. He recruited Newcombe, a conservative writer he respected, to write a column. Though, as the first editorial declared, the Voice was founded to “analyze issues in a liberal light,” Newcombe’s recruitment demonstrated a commitment to well-rounded coverage.

Their reporting ranged from conflict in the Middle East to anti-war protests to the real possibility that the School of Foreign Service would shutter its doors. In their third editorial, the editors acknowledged the widespread demands for change and reaffirmed their commitment to cover as much of campus and the world as they could.

“Student activism and concern have never risen to such a level at Georgetown as they have during this past year,” the editors declared at the end of the spring 1970 semester. “The Georgetown Voice was born amidst the new activism. As a new publication, we had to face many problems; and we made mistakes. We have not been satisfied with our performance, and we never will be.”

The Voice strove to improve its coverage over the next few years. It stayed committed to reporting on issues at a university, national, and international level. “We were dealing with the world, not just campus,” Schroth said.

The ripple effects of the up-and-coming publication were felt in The Hoya’s office. The other newspaper began to expand the scope of its coverage but soon faced a shortage of news writers. In 1970, this shortage, along with a smaller budget for media groups, led The Hoya to propose a merger with the Voice.

The front page of The Hoya’s Nov. 12, 1970, issue called for the merger, referencing funding as its primary motivation. “In our judgement, the University will not be financially able to maintain two undergraduate newspapers in the coming years,” the piece read.

The Hoya’s editor-in-chief also added that the “ideological differences that lead to the founding of the Voice no longer exist.” According to Di Sciullo, Pisinski, Newcombe and the other staffers discussed the offer but ultimately felt that they could not compromise on their vision. “They were the status quo,” Di Sciullo said. “We had momentum on our side.”

In an editorial published on Nov. 17, 1970, the Voice’s editorial board rejected the proposal.

“Times arise, however, when two viewpoints on an issue will want expression, when editorial stances will have to differ to insure full, adequate articulation of differing opinions within the university community,” the editorial read. “Two newspapers serve this function.”

Fifty years later, there is still room for two news outlets on campus. When the Voice reached out to Schroth, now 86, for this issue, he was pleased to hear that the Voice has endured. “I had hoped it would last this long,” Schroth said. “I knew there was a risk.”

As the Voice’s first moderator, Schroth watched the founders work hard to push the envelope, to keep publishing fresh and engaging stories that would make readers come back for more.

“Sometimes when something is popular it’s because it’s new,” Schroth said. “Well, if you are new every week, you can hold onto them.”

[…] activists began passing out flyers on campus, and Steven Pisinski (COL ’71) left The Hoya in 1969 to found the Voice, which Winship went on to join. New Voice staffers, many of whom were former Hoya writers, cited […]