The year is 2007: between Lindsey Lohan’s 84-minute stint in a California jail and Britney Spears’ yearlong breakdown of shaved heads and smashed umbrellas, media sympathies for female celebrities and their mental health are at an all-time low. On late-night talk shows, punchlines abound. It seems almost fated that, during this year, a national news frenzy would erupt around a love triangle melodrama of star-crossed lovers, extraterrestrial extramarital affairs, and astronaut-on-astronaut crime with a deranged, diapered woman at the forefront.

In February, Lisa Nowak, a then NASA astronaut, made headlines after her 900-mile journey from Texas to Florida equipped with BB gun and diapers (referenced in one police report of dubious reliability.) Her mission was to kidnap the new flame of also-astronaut William Oefelein, with whom she had previously been in a relationship. Television programs latched onto the striking juxtaposition of the orange flight-suited woman in her official NASA photograph and the woman pacing back and forth in her holding cell, mindlessly rambling about her time in space: the downward spiral of a woman once on top of the world.

Lucy in the Sky (2019) does not tell the story of Lisa Nowak—at least not in name. Her attorney, in fact, considers the movie to be “an entirely fictional story and not based on reality.” Though it’s impossible to overlook the similarities, it’s clear that director Noah Hawley (small-screen showrunner of “Fargo” and “Legion”) sought to walk the fine line between inspiration and adaptation. Spoiler alert: there are no diapers in this film.

Upon returning from interstellar travel, Lucy Cola (Natalie Portman) struggles to find her footing on solid ground. Once you’ve seen your house from space, Lucy tells us, it’s hard to go back to dining out at the local Applebee’s. This sense of feeling adrift begins to manifest in worrying ways: in endangering herself during training, muttering strings of launch checklists under her breath as an anxious tick, and committing infidelity. Much of the drama centers on the incestuousness of NASA—Lucy strays from her husband in a truck bed tryst with astronaut Mark Goodwin (Jon Hamm), who eventually finds himself falling for another, younger astronaut, Erin Eccles (Zazie Beetz). The two women, Lucy and Erin, vie for a space on the mission ‘Orion’ and the affection of the fickle Goodwin.

From the first moments of Portman’s hollow twang and regrettable wig, Lucy in the Sky throws subtlety out the window. However, its most egregious affront to the audience is the aspect ratio, which continually changes to show Lucy’s widescreen immersion in space and her letterboxed claustrophobia on Earth. Much of the terrestrial scenes are shot in the squarish 4:3, deriving us of the full scope of the (sometimes) gorgeous cinematography. Everything in the world is small compared to the vastness of space—and if this wasn’t made clear through Lucy constantly saying as much, the borders of the frame closing in and expanding are a ceaseless reminder. This gimmick seeks to be immersive, showing us the world through Lucy’s eyes, but it’s more disruptive of her narrative than anything else. In a film where Lucy should be the star, the aspect ratio steals the show.

One generation to another, Lucy’s tough-as-nails Texan mother tells Lucy’s niece, Blue Iris (Pearl Amanda Dickson) to forget about her deadbeat (poet!) dad and zero in on her astronaut aunt: “You keep your eye on this one. She’ll show you how it’s done.” The edict is directed at the audience, too—in the eyes of the screenplay, she’s a woman who can do no wrong.

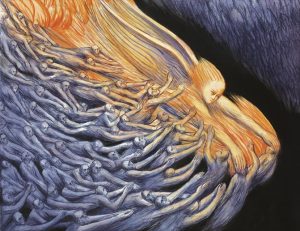

This unquestioning look at Lucy and her experiences occasionally dips into the romanticization of her mental illness. Through the heavy-handed, mystifying visual motif of cocoons and butterflies, Lucy in the Sky broadly gestures at the idea of metamorphosis: in zero gravity, Lucy is suspended upside down like human chrysalis swaddled in the astronaut equivalent of a sleeping bag and a cocoon hammock hangs in her yard on earth. Cradling her niece’s domed butterfly habitat in her arms, Lucy berates her husband: “Why did God make something that has to destroy itself in order to fly?” But there’s nothing beautiful about Lucy destroying herself, regardless of the film’s glorification of “strong” women and their need to put themselves in danger to succeed.

Despite the faux-feminist posturing of camaraderie between Lucy and Erin, there’s an undertone of hostile rivalry that runs beneath their conversations of girl power solidarity. The subtext is: this space program ain’t big enough for the both of us (a sore subject for NASA, who recently postponed the first all-female spacewalk for want of two properly sized spacesuits). Here, Lucy in the Sky takes a notable detour from its source material—Air Force Captain Colleen Shipman, Erin’s real-life analog, was the victim of Lisa Nowak’s malicious attack, but the film swaps the scenario, having Lucy attack Mark Goodwin while Erin looks on in horror. Lucy cautions Erin against two-timing men, the film seemingly framing the assault of Goodwin as “sticking it to the man.”

There’s a wink-wink, nudge-nudge moment for the female moviegoers when a superior brands Lucy as “too emotional.” She shoots back that he wouldn’t be saying the same to man. Of course, a few scenes later, she’s driving across the country with her underage niece and a gun, hell-bent on murdering a man she felt slighted by. It’s not over-emotionality; it’s mental illness, but Lucy in the Sky’s screenplay doesn’t care to make the distinction. Pinning Lucy’s erratic behavior on the singular event of going to space suggests something that the film pretends to so strenuously deny—that women, being hysterical creatures, are unfit to walk the halls of NASA. Space travel, after all, should be left to the clearheaded menfolk.

Hawley, confronted with a semi-biopic screenplay, decided to skirt the typical genres for profiling controversial figures—thriller or dark comedy, à la the comedic yet deeply empathetic I, Tonya (2017)—to opt for a new type of approach. Lucy in the Sky was intended to be “a story of a psychological decline” with “elements of magical realism” to spotlight Lucy’s subjectivity. Instead, with an unbalanced amalgam of campy, riveting, and downright boring scenes, the film takes a noncommittal middle ground that gives it a wildly uneven tone and turns Lucy’s journey into a punchline. Lucy in the Sky is sans diapers, but it handles its true-crime drama no better than the tabloid headlines.