Just one stroke of Timothy Johnson’s paintbrush bites like the blade of a guillotine, leaving his subjects headless and bleeding off of the canvas. The local artist’s latest exhibit, Fables of Decapitation: I knew I would die long ago, is a collection of paintings featuring himself and his friends along with a string of biblical, mythical, and historical figures—often without bodies to match. With each painting, the audience will find themselves reliving gruesome tales like those of Marie Antoinette, Anne Boleyn, and David and Goliath. Showing at Touchstone Gallery through tomorrow, Fables of Decapitation puts a colorful twist on an otherwise grim topic, poking fun at the macabre and dancing on the edge of death itself.

Although counterintuitive, the defining characteristic of Johnson’s collection is humor. The artist’s cheeky perception of death is not weighed down by the usual doom and gloom associated with disembodiment. Instead, his work will make the audience laugh and then immediately gasp at their own amused reaction. A series of headless portraits propped up on wooden stakes is no cause for comedy—until you read the titles. “Close shave.” “I can’t feel my toes.” “A little off the top.” It’s difficult not to chuckle at such dark puns.

And oddly, even the subject matter is playful. After all, it is an exhibit about fables, and any good story has some wit to it. Like the audience themselves, the characters in each piece seem to lack any kind regard for the seriousness of each situation. In “Marie Antoinette…’Let Them Eat Cake,’” a ravenous and delighted crowd awaits their former queen’s execution, stuffing their faces with bright pink cake, some even straining their heads to get a better look. For them, it’s dinner and a show. In “Hey Battah, Battah… Swing Battah, Battah. Perseus Beheading Medusa,” Medusa’s sliced head is spraying blood across the field as Perseus whacks it like a baseball. But instead of looking horrified, Medusa looks almost bored with the corners of her mouth turned down in an expression that sighs, “Well, it was bound to happen.”

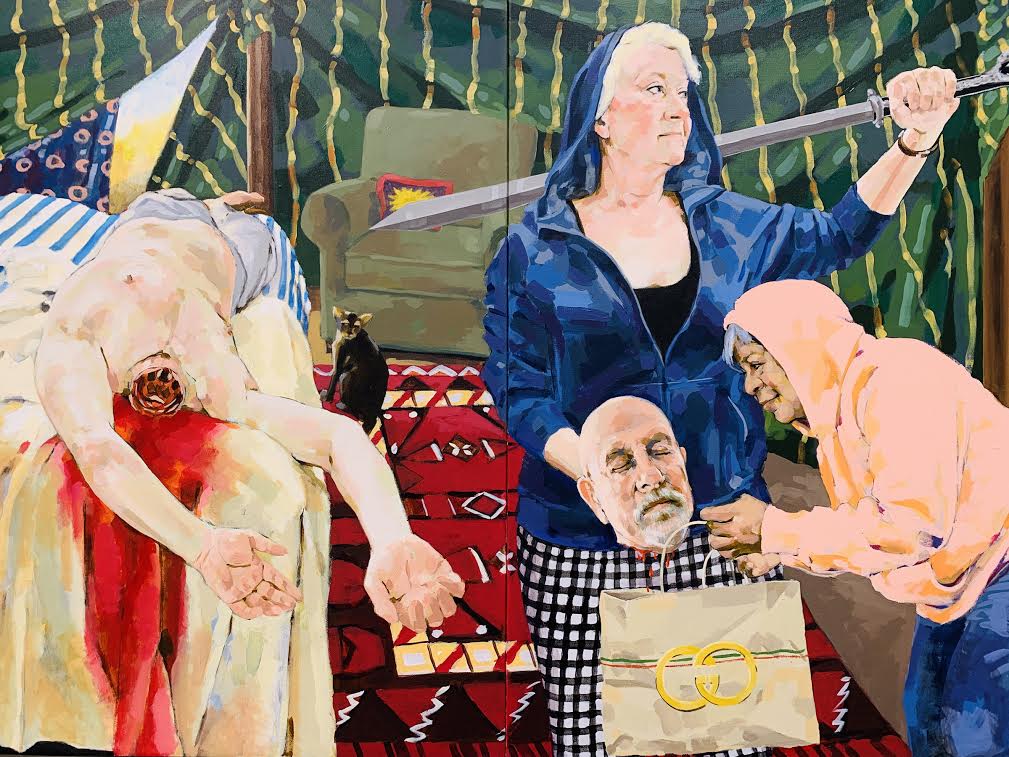

Much of Johnson’s work weaves historical and biblical narratives with Western popular culture. Such mash-ups, as in the likening of the beheading of Medusa to hitting a homerun in baseball, include adding a Gucci bag to the scene of Judith murdering Holofernes. The most poignant of these crossovers is “A Victorious David Perched on the Head of Goliath” in which a young, slingshot-bearing David stares down at the viewer from the massive head of the fallen giant. While the story of David and Goliath is an ancient one, Johnson’s David wears athletic shorts and the mischievous look of an American cartoon character like Dennis the Menace. This utilization of contemporary culture amplifies the savage nature of beheading by suggesting its existence in our modern society. David and Goliath is a tale of heroism, but by portraying David as a young child that could live in the viewer’s neighborhood, the killing suddenly becomes much more disturbing. Contrastingly, the modernization of these deadly tales fits with Johnson’s witty theme. It makes the paintings have a lighter, almost comedic tone and challenges the viewer to spot all of the references he may have included.

Yet Johnson is not only the executioner, he is also a victim. Rather than simply playing God, the artist depicts his own ghastly mortality, even going so far as to insert himself into the stories he is retelling like “Perseus is Dispatched to Behead Argus and Free Lo” and “Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes.” In fact, the first painting that the audience will encounter is his self-portrait, hanging eerily alone on its own wall, adjacent to the rest of the pieces. “Laughing my head off” shows Johnson’s severed head propped up against a dark to light blue gradient that mirrors a stormy sky. His eyes are slightly rolled, his tongue is out, and he is wearing a bright red clown nose. The entire painting is on a literal wooden stake that extends to the floor. As the title implies, he is laughing in the face of death, as if to accept that everyone dies and to refuse to be weighed down by that. Where so many artists focus on the sinister reality of our fleeting lives, Johnson scraps that, making even the most horrific of deaths seem funny, including his own.