Audio: Listen to Rose Dallimore read her piece, “On falling in love with a dead author.”

Three-quarters of the way through Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life, I stalled on the Encyclopedia’s letter S.

A friend recommended the book to me because he thought I would connect to the unusual format and eclectic, pithy style—I am the sort of reader and writer that loves a good zinger, six-word horror story, or surreal snapshot of narrative. My fascination with the short and sweet is due, in part, to my tragically weak attention span. However, I also think that the most realistic depictions of hilarity and profundity are momentary.

The first few pages of the book were delectable—I quickly fell in love with Rosenthal’s fascination with words, signs, and advertisements. Through them, she transformed quirky anecdotes into comments on the uncanny, entertaining bits of human psychology. I grew obsessed with the book’s encyclopedic format. With entries ranging from “Chef’s Hat” to “Office Depot” to “Shameful,” Rosenthal summarized a life that, while maybe more ordinary than epic, seemed full of joy and glimmers of the satisfyingly absurd. In parking tickets and childhood photographs alike, Rosenthal underscored the aesthetic and hilarious, the random and poignant, and the quotidian and tragic in bursts of story that are—as she pointed out herself—deeply personal and honest. It is this honesty that makes her writing so uniquely moving.

She also outlined the disjointed career path her writing has taken her. As a writer with no idea of what I want to pursue, I found this reassuring. She found herself in the work she did and did it because she found herself in it. From working in advertising to writing essays for magazines to writing this book, Rosenthal was stalwart in her individuality. She overcame her self-admitted struggles with fiction and her own short attention span by being impeccably descriptive—capturing truth in a way that made me feel like reality is happier than I often think it is, that the daily is a gift. Rosenthal extolled this candid gratitude in a way that other writers using more traditional structure and self-censored tactics fail to do.

I believed in her appreciation for the absurd, her love for her children and friends, and her unbridled humor in the face of some really dark shit. One of the most beautiful relationships she painted was the one between her and her husband, which she wrote into hundreds of reflections on sweet, goofy togetherness, and wrote it truthfully. I believed in her positivity and passion for life. For perhaps one of the first times in my self-important young writer’s life, I thought, this is a writer I need to learn from.

I thought this over and over again as I sped through the second half of the book. I have consumed these pages in quarantine, and they have meant a lot to me. My saving grace in the face of isolation has been lugging one of my uncomfortable dorm chairs onto the patio and reading Encyclopedia in the fresh air each morning. One of these mornings, I sat out there, sweating as the sun rose, feeling the hope and excitement of this writer and this style assure me, as if to say, the way I write—the way I think—can be dynamic, it can be what I make it, and it can be successful. I was almost pissed that Amy Krouse Rosenthal had written a book I would have liked to write someday. I wanted to thank her and ask her for advice, to send her an email, to see how her thoughts have changed on these entries in the 16 years since she published the book. For reasons I can’t quite explain, I felt hopeful.

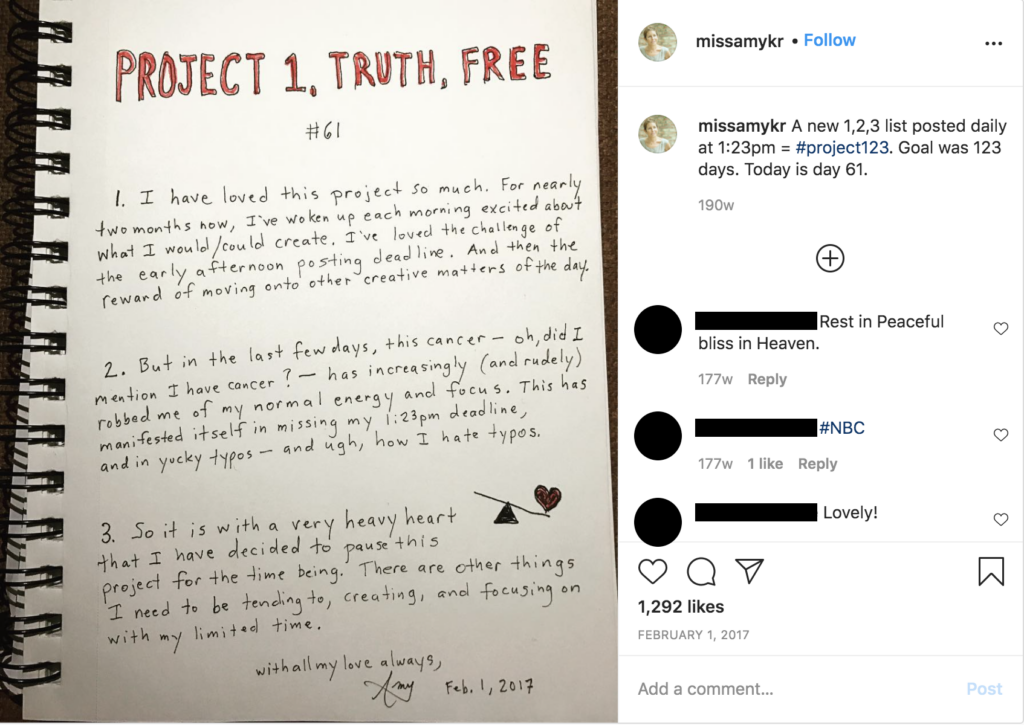

As these thoughts buzzed in my head, I pulled out my phone to see what else she had written. I thought I had heard her name in reference to the multitudes of beloved children’s books she wrote, but I was sure she also must have written other books for adults in subsequent years. Rosenthal seemed to me like a hip and with-it writer, young at the time of publishing Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life in 2004, so I looked her up on Instagram. When I found her page, I immediately noticed it had been dormant since 2017. I clicked on the most recent post.

March 27, 2017: “A note from Amy’s daughter, Paris: Many of you know that my mom had an Instagram project where she posted a new 1,2,3 list daily at 1:23 PM. Her goal was 123 days. She made it to day 61…”

My heart began to settle down into my ribcage. I saw the same comments, again and again: “We miss you, Amy.” I scrolled to the penultimate post, the last one from Amy herself.

My eyes welled up, and the sort of nausea felt with an entirely unexpected tragedy rose in my throat. I sat with the sun starting to burn my scalp, my mask and tears and sweat fogging up my glasses, the book clutched against my stomach.

First, I was hit with this feeling of betrayal and disappointment—Amy, what the hell? What? Wait, come back! I was just getting somewhere with you. You’re the kind of writer I want to be. I have a question! I have an idea! Can I run something by you? What do you think? Hello?

I realized also that part of my shock stemmed from how personally relatable I found her. In thinking, I want to be like you, I think I am a little like you, Now what?, I was confronted with questions and ideas about my own future. When I was reading her Encyclopedia, my vision for my life felt hopeful and informed by a new perspective. When I found out she was three years dead, I had to consider the inevitable loss and pain that still awaits me—an optimist, a lover of daily life, invariably passionate—down the road. Existential concern wormed its way into my mind, wickedly turning my stomach.

Then, there was guilt that settled on me immediately after the grief and concern. Who am I to cry at your death? As if I—not your husband who you loved so much, not your children who shaped your life, not the entire world—lost you. And they all lost you three years ago, when I had no idea who you were, or that I would love your writing, or what you thought about things, or that you were being ground down by ovarian cancer until you died. I didn’t know Amy Krouse Rosenthal. I didn’t know of her until a week ago. My sadness felt selfish. I felt like I had used her as a symbol rather than a human being.

I felt this profound deflation as I began to think about this loss in the context of the book, which I still had a quarter left to finish. I prayed that Amy stood by her every word—hopeful, goofy, and meaningful. But I was concerned that perhaps she didn’t. She wrote Encyclopedia years ago, before her children grew up, before she grew up, before she knew she had cancer, and before she began to die. I couldn’t believe she only made it to Day 61 of her project.

I dragged my chair inside with a burning need to find some semblance of meaning. On my laptop, I googled Amy Krouse Rosenthal again and came across something I hadn’t seen in a long time. She wrote a Modern Love Column, published in The New York Times on March 5, 2017, titled “You May Want to Marry My Husband.” It was published ten days before Amy died. I won’t speak for it; please go and read it yourself. I remember reading it around the time it was published and gained viral popularity in 2017. I read the column again, and I felt like suddenly I understood it better—understood Amy’s personality and her relationship with her husband. Most importantly, I was struck with the beauty and power of her legacy. Her parting gift to her family and her readers was still inexplicably optimistic, silly, and kind.

Graphic by Allison DeRose

Graphic by Allison DeRose

Closing my laptop, I did not feel a sense of resolution. Even now, a mild existential discomfort has yet to leave me. I do feel, though, like it is worth it to let an experience like this crush you for a second. We often hear of death in a daily, non-personal sense. It is a part of life. I think for something to actually touch your heart lately is a blessing, a shock into the depths of each day, a moment for re-evaluation. More than anything, grieving a human loss is sacred, both symbolically, for who and what a person was to you, and literally—for who and what a person was.

I have a quarter of the book left to read. It has been sitting on my kitchen counter, dog-eared at “Safire, William,” “Sampras, Pete,” and “Sandwiches.” To be honest, I have been scared to pick it back up, as if the entries will have changed to “Loneliness” and “Cancer, Ovarian” and the meaning I found before will become impossible to relocate.

Deep down though, I know this is not the case because Amy knew about life and death before she was dying. She would not have been able to write so clearly on joy otherwise. Her ordinary was extraordinary, not for the events of her life themselves, but for her reactions to them, for her analysis of them, for her love in the face of them. I think she understood what it is to live a good life.

I did not expect to fall in love with a dead writer amid a global pandemic and a social revolution. I did not expect to be able to recall this peculiar feeling for more than a few hours. Yet here we are. I think this experience has changed me, in that daily sort of way. Because love and death and joy are daily occurrences––the building blocks of a so-called “ordinary life.”

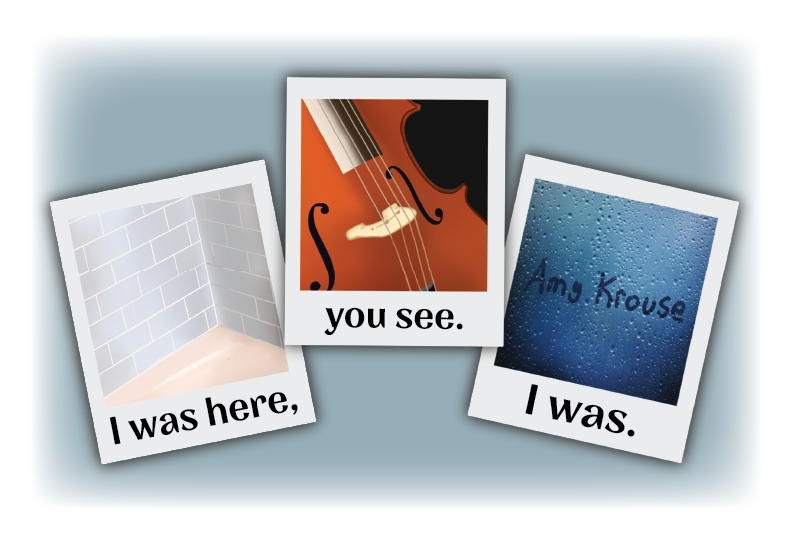

Update: I finished the book this morning. This was the final paragraph of the volume, the only entry under the letter Y:

You

Perhaps you think I didn’t matter because I lived ___ years ago, and back then life wasn’t as lifelike as it is to you now; that I didn’t truly, fully, with all my senses, experience life as you are presently experiencing it, or think about ____ as you do, with such intensity and frequency.

But I was here.

And I did things.

I shopped for groceries. I stubbed my toe. I danced at a party in college and my dress spun around. I hugged my mother and father and hoped they would never die. I pulled change from my pocket. I wrote my name with my finger on a cold, fogged-up window. I used a dictionary. I had babies. I smelled someone barbecuing down the street. I cried to exhaustion. I got the hiccups. I grew breasts. I counted the tiles in my shower. I hoped something would happen. I had my blood pressure taken. I wrapped my leg around my husband’s in bed. I was rude when I shouldn’t have been. I watched the cellist’s bow go up and down, and adored the music he made. I picked at a scab. I wished I was older. I wished I was younger. I loved my children. I loved mayonnaise. I sucked on my thumb. I chewed on a blade of grass.

I was here, you see. I was.