D.C. has an alternate geography hidden to its visitors. Beneath the national monuments, city blocks, historic neighborhoods, and federal buildings lies a map of food deserts, segregation, health care gaps, environmental disparities, and now, the disproportionate repercussions of COVID-19 on minority communities.

The pandemic, having reached its one-year anniversary this month, has impacted the lives of millions of Americans across every state, territory, social class, and race. In that way, the coronavirus is an equalizing force. But in another, more insidious way, it is the epitome of discrimination. COVID-19 has led to disproportionately high numbers of deaths in Black, Hispanic, immigrant, and disabled communities across the country, including within Washington, D.C., and has laid bare the startling systemic inequalities present in the District.

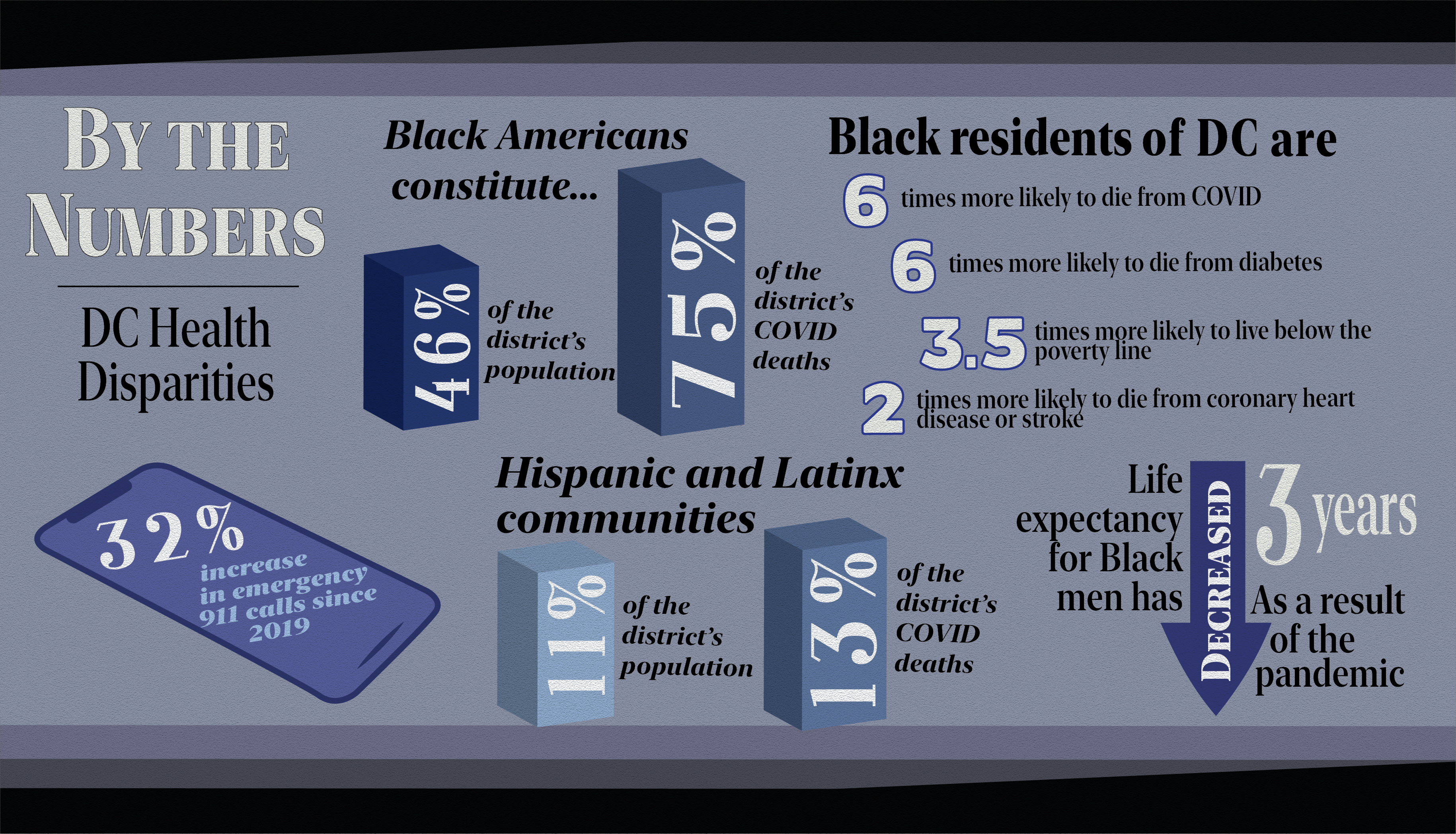

Black Americans have been dying of COVID-19 at a far higher rate than their white counterparts, as they constitute 46 percent of the population, yet make up 75 percent of the District’s COVID-19 deaths. Life expectancy for Black men has decreased three years as a result of the pandemic. According to Georgetown history professor and founding chair of the District of Columbia Commission on African American Affairs, Maurice Jackson, Black residents are approximately six times more likely to die from COVID-19 than other racial groups.

The second-highest number of fatalities has been within Hispanic and Latinx communities, who make up over 11 percent of the city’s population and 13 percent of its coronavirus deaths. The death toll is large, but has distinct faces and names—including Mayor Muriel Bowser’s sister, Mercia Bowser. These health care statistics emerge from a collage of historic and contemporary factors—environmental, educational, and economic.

These disproportionate deaths are not surprising, but rather, on track with D.C. health care disparities that have existed for decades.

In 2016, Jackson was asked by Bowser to investigate reasons for the exodus of residents from the District, focusing on socioeconomic disparities that led to an emigration of the city’s Black population. For this purpose, Jackson commissioned a study, “The Health of the African American Community in the District of Columbia: Disparities and Recommendations,” from Professor Christopher King from the Georgetown School of Nursing and Health studies.

The 2016 report found that Black residents in D.C. were six times more likely to die from diabetes, 3.5 times more likely to live below the poverty line, and twice as likely to die from coronary heart disease or a stroke than their white counterparts due to disparate living conditions.

“You can’t separate the health care of people from the living conditions overall,” Jackson said in an interview with the Voice. “Health care is a condition of and is directly related to the type of work you have, the kind of stress you have, its related to family background.”

Jackson, who has lived in Washington most of his life, argues that disparities in D.C. COVID-19 cases and health care are inherently tied to the city’s racial economics and geography. Washington is one of the most segregated cities in the United States. The District is split into eight wards, with the eastern districts, wards 7 and 8, separated from the rest by the Anacostia river. According to the 2016 report, Black residents make up approximately 5 to 10 percent of the D.C. population in western wards of the city and more than 90 percent in wards 7 and 8. Zip codes 20032, 20020, and 20019—all on the east side of the city—have the worst Healthy Community Institute’s SocioNeeds Index values in the nation. The indexes evaluate socioeconomic factors that contribute to hospitalizations for preventable chronic illnesses, including obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure—all pre-existing conditions that exacerbate COVID-19.

These zip codes include the Historic Anacostia neighborhood, one of D.C.’s original suburbs located east of the Anacostia River. Its initial zoning prevented the sale, rental, or lease of properties to Black Americans, but by the 19th century, Anacostia had become a Black cultural center and the home of Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Today, Anacostia is home to almost half of all Black D.C. residents.

The neighborhood, however, is also one of America’s ‘food deserts,’ with a dearth of grocery stores and affordable, healthy food options.

“Food deserts are places where there are no grocery stores within that place where you can easily access,” Jackson explained. “If you go to Anacostia or Ward 7, or in some neighborhoods, there are no grocery stores. You can’t walk to the grocery store.”

For families living in Ward 7 or Ward 8, where households are less likely to have cars, grocery store trips often require use of public transportation, a service that has been vastly limited and carries a heightened danger during the pandemic.

“If you have Whole Foods, you are going to hopefully get yourself a nice salad—it may cost a fortune, but they don’t have Whole Foods in the communities. The biggest stores in D.C. are Safeways and Giants, but they don’t have those in the communities either,” he explained. “You see people in wards 7 and 8 relying on corner stores where the food is not nutritional.”

Virtual learning during the pandemic also means that students who relied on D.C. public schools’ lunch programs lose a source of nutritional meals in their daily diet. “You have Black and Hispanic kids who are missing the whole year of school,” Jackson said. D.C. public schools are some of the most segregated schools in the nation, meaning that the disappearance of a food source is much more significant for students in wards 7 and 8 compared to students in wards with more food sources. With the loss of a sustainable food option, young people east of the Anacostia often turn to corner stores as stopgap measures for nourishment.

Food insecurity not only impacts people’s day to day nutritional health, but prevents effective treatment of chronic conditions. Diabetes, for instance, requires greater food regulation, which may be challenging for communities without sustainable options.

King explained to the Voice that food deserts are most likely to impact Black and Hispanic communities, as well as children, the elderly, and people with unstable housing. These disparities have existed for decades, but have been exacerbated by COVID-19.

“The number of households that experience food insecurity in the region has jumped from 10 percent pre-pandemic to 16 percent during the pandemic,” he said.

Inequality doesn’t stop there. According to Jackson, educational policies in D.C. public schools also impact general health patterns.

“A couple of years ago, they took physical education out of the schools,” he said. “That means that you take one of the main ways that children exercise, especially if they live in apartment buildings, and you saw the rise of obesity and large numbers of diabetes.”

Even the geography of the city leads to the disproportionate prevalence of COVID-19 and chronic illness in communities of color. In the District, primarily Black neighborhoods are often situated near large intersections and waste distribution centers. According to Jackson, air pollution generated by areas like these increases the risk of cancer. The 2016 report found that Black men were three times more likely to die from prostate cancer and Black women were 1.5 times more likely to die from breast cancer than white populations, partially due to segregation within the District that often forces Black residents into unhealthy living conditions.

Similarly to Black communities, immigrant families are experiencing some of the worst repercussions of the pandemic. Undocumented individuals are less likely to receive medical insurance benefits or be eligible for government relief funding, and are more likely to live in crowded environments.

“In many cases, you have people who are immigrants who have come to America for a better life, they live in apartments where three or four families live together, no insurance. Widespread COVID,” Jackson said.

The impact of COVID-19 on communal living environments is best illustrated by D.C.’s largest apartment complex, Woodner Apartments. The complex has approximately 2,000 residents, including Latinx immigrants and others seeking affordable housing in Columbia Heights, against the backdrop of a gentrifying city. According to residents, COVID-19 cases have rapidly spread through the complex, leading to a 32 percent increase in emergency 911 calls since 2019.

“You had an inordinate number of deaths of people, especially people with pre-existing conditions in the city because of the close proximity of how people live, but especially in apartment buildings,” Jackson said.

Despite calls for help from the city, D.C. Health Director LaQuandra Nesbitt responded to reports of a breakout within Woodner by eschewing the city’s responsibility for apartment-to-apartment spread and leaving residents to fend for themselves.

This multifaceted segregation is no random phenomenon, but emerges following decades of gentrification throughout the District. Over the last 30 years, white residents have gradually moved into traditionally Black neighborhoods, and longtime residents have been forced to leave as housing prices rose. The movement of white citizens into new areas of D.C. like Columbia Heights and the Navy Yard has not improved food security or educational resources for Black residents—it only made them further out of reach.

“In D.C. you have a large African American population, but you have so many who left because they couldn’t afford the city, couldn’t afford mainly housing,” Jackson said.

While it may be assumed gentrification improves services as the city becomes wealthier, this is not the case for Black and immigrant communities within the city. While D.C. is getting whiter and wealthier, Jackson explained that two-thirds of the people who work in D.C. reside in Maryland and Virginia. Therefore, the District and its increasingly gentrified neighborhoods do not receive the benefit from taxes on the wealth generated within its borders.

For King, a D.C. native, the gradual gentrification of a Black middle class due to rising housing prices within school districts is linked to health care.

“This is my home. I have seen how the city has changed. People who have lived here all of their lives are struggling because of gentrification. The cost of living has become unsustainable. Cultural hubs are rapidly dissipating and residents are experiencing a lack of community and social cohesion,” he explained. “All of these issues impact physical health and well-being.”

King argues that whether families have the insurance or income to pay for treatment or not, disparities in living conditions will inevitably result in disparities in health care.

“People must understand that health is mostly shaped by where we live, learn, eat, and play,” King said. “We can have health insurance and the best medical care in the world, but if the quality of the community north of main street is different when compared with south of main street, we will see differences in health outcomes.”

D.C. lacks any form of a public hospital, leaving those without insurance or unable to access health care benefits due to their immigration status or income completely without a safety net.

“Especially for people who don’t have insurance, what they do is go to emergency rooms as they may not have a family doctor. Everybody should have their family doctor and should not worry,” Jackson said.

The benefit of the emergency room is that it is required to treat a patient by law, regardless of insurance or payment ability. Treatment for pre-existing conditions and chronic conditions, however, require family doctors and cash out of pocket.

“People are paying 40 or 50 percent of their income for health care, so how do you pay rent? How do you pay for health care? How do you pay day care? How do you pay for transportation? We have all these things compounded together,” Jackson argued.

Accessibility to health care in D.C. extends far past Black neighborhoods. Disabled communities in D.C., across racial identities, have also disproportionately suffered from COVID-19 due to a lack of access to hospitals and caretakers. Mary Ellen Dingley works at L’Arche Greater Washington, D.C., a nonprofit organization that offers housing and support to people with disabilities. According to her, the pandemic has disproportionately impacted their community due to a lack of access to hospitals and caretakers.

“Many people with disabilities face challenges in accessing quality, dignifying health care across the USA—doctor’s offices might be inaccessible, people with disabilities can be denied organ transplants, or medical staff might not treat people with disabilities with respect, for some examples,” Dingley wrote in an email to the Voice.

While people with disabilities are six times more likely to die from COVID-19, according to Dingley, it is nothing out of the ordinary as there is a longer history of health care inequities for the disabled community. In 2017, a federal judge ended the longest-standing disability court case of its kind: a 40-year lawsuit about the abuse, neglect, and deaths of mentally ill residents under the District’s guardianship. “For people with disabilities in DC, there is a history of them receiving poor treatment generally,” Dingley explained.

Even with minor improvements, inequities in D.C. vaccine distribution have impacted the disabled community. Earlier this year, a disabled person’s access to a vaccine depended on the type of Medicaid waiver they held, according to Dingley.

“Many people advocated for intellectual and developmental disabilities to be seen as risk factors no matter the type of waiver, but it took months for their voices to be heard,” she explained.

Disparities in vaccine distribution are even more blatant within Black communities. Although the death toll has been highest in wards 7 and 8—all east of the Anacostia—D.C. Health data shows that the majority of vaccination appointments have gone to whiter, richer wards. At the end of January, over 2,000 residents of Ward 3 had scheduled vaccine appointments, while only 197 from Ward 7 received the same. In response, the D.C. government flooded these wards with extra appointment slots in an attempt to correct the gap.

Despite speculation that Black individuals are opting not to receive the vaccine, resulting in lower vaccination rates in primarily Black neighborhoods, King pushes back at this assumption.

“Vaccine hesitancy (due to a history of medical experimentation on Black and brown bodies) plays a role but now we are seeing more and more people of color express willingness to receive the vaccine.”

This disparity in vaccinations is far more explained by inaccessibility, as many members of wards 7 and 8 do not have immediate access to a computer to sign up for an appointment or transport to a vaccination site. King stressed the need to adapt vaccine distribution to improve localized access.

“Meeting people in neighborhood settings with trusted community leaders is key. Churches, grocery stores, barber shops and beauty salons should be explored. Twenty-four hours vaccination sites may be especially helpful for those who have multiple jobs and/or non-traditional work,” he suggested.

As one of the largest private institutions in the District and sitting in the wealthy and white Ward 2, Jackson emphasized Georgetown University’s role in health care disparity and future equality in the D.C. community. Both Georgetown and contracted Aramark employees face a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 thanks to the presence of students on campus, with numbers of new cases reported among workers on the main and medical campus each week. Students have already come together to support some Georgetown employees who have suffered financially or physically suffered during the pandemic. Transportation may also become increasingly challenging for workers, as major Georgetown bus lines, including the D1, D2, and G2, are also expected to be rerouted or eliminated due to Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority budget cuts.

According to Jackson, President John DeGioia has personally supported the reports, and the university is devoting resources to academia and establishing a Racial Justice Institute. That said, Jackson believes there is more to be done to support the community we are a part of, not just campus.

“I am afraid they are not paying much attention to Washington, D.C. You start with your home. This is a testing ground,” he said.

Jackson concluded that all these disparities—economic, racial, educational, and environmental—are compounded and made clearer during a health crisis like COVID-19.

“Suffering and struggling all the time, it is a big point of stress,” he said. “It has high blood pressure, and when you can’t afford to take care of your children, when you can’t pay the bills, when you worry about their education, it brings down the quality of life easily.”