It may be common to see students panting as they brave the hill from Leo’s to Lau, squinting at tiny or almost illegible fonts on PowerPoint presentations, and struggling to maintain a tenuous balance between internships, work, grades, and social life. But for students with disabilities at Georgetown, these manifestations of Georgetown’s inaccessibility on campus are no mere inconvenience, but rather represent active hindrances to their daily lives.

Despite the added pressures and complications presented by a global pandemic and a virtual environment, student activists’ progress—an accumulation of years of disabled activism—continues to push the university and its climate toward increased accessibility. These students know improvements to Georgetown accessibility will not happen automatically with the return to campus, but require active participation from abled students, faculty, and administrators. Activists are hoping for recognition of and solutions to the inaccessible environments and behaviors that pervade Georgetown.

“The vast majority of non-disabled students severely underestimate how inaccessible our campus is,” Dominic DeRamo (COL ’23) said in an interview with the Voice. “I encourage non-disabled students to think about our space and how our space is constructed and who feels included as a result.”

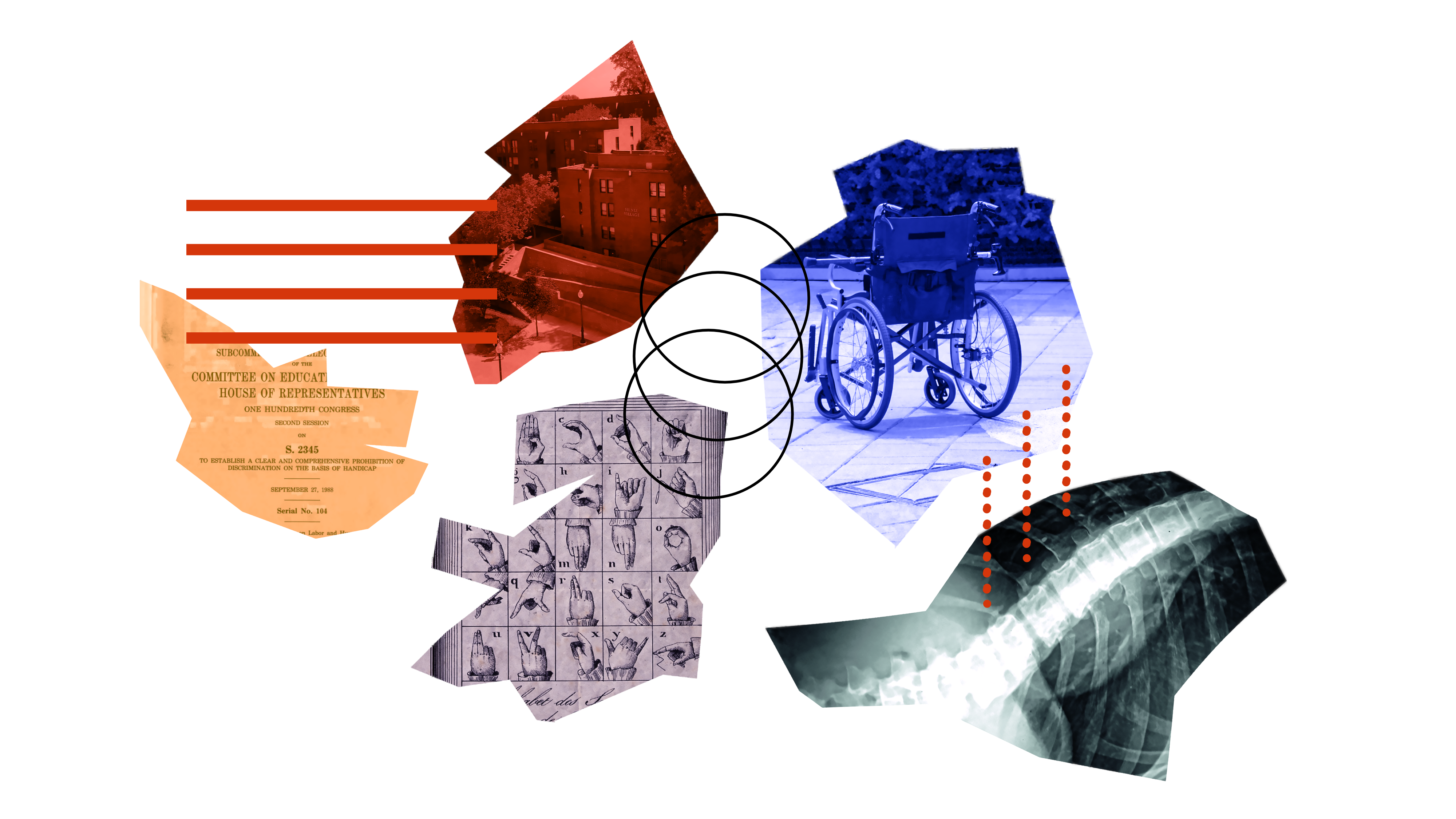

One doesn’t have to look far to see examples of inaccessibility on Georgetown’s campus. In 2018, Arrupe Hall failed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliance standard for having doors that require more than five pounds of force to open, and White-Gravenor was required to undergo renovations to add more than one ramp (the original ramp led directly to the basement and was often locked) to the nearly century-old building.

These examples don’t even begin to touch the difficulties of the rocky brick paths across the neighborhood for those in wheelchairs, or the long distances students may have to travel to find a ramp to their destination.

Georgetown is just one example of how an inaccessible environment filled with “physical, attitudinal, communication and social barriers can shape interactions with people living with disabilities.” This definition of disability—known as the social model—relates to the interplay between one’s environment and disability. It was adopted by disability scholars in the 1960s and has been guiding disability activism ever since.

DeRamo is one of several activists on campus who have taken the lead on giving visibility to accessibility issues. He is a part of the GUSA policy team for accessibility, the Georgetown Disability Alliance, the student team pioneering the HoyaLift program, and the group working for a Disability Cultural Center (DCC).

Efforts of disabled activists from a variety of groups came to fruition in June of this year when the university took the first major step, enshrining the Disability Empowerment Endowed Fund to fund initiatives that support students with disabilities in the Georgetown community, including a DCC.

The fund was created following a $50,000 donation from Tiffany Yu (MSB ’10), but the university says it will need $100,000 total to officially launch the fund. The remainder is being crowdsourced from community donations. According to the Georgetown Disability Center Instagram, launched by DeRamo, Nesreen Shahrour (NHS ’23), and Gwyneth Murphy (SFS ’23), all of whom serve on the GUSA Accessibility Policy Team, students received $540 toward the initiative in Venmo payments to @georgetownDCC in the first two weeks.

To students like Murphy, disability resources on campus are essential for making students feel welcome. “The first thing I did when I was looking for colleges was research their disability services and what the campus was going to be like for me in that specific sense,” said Murphy.

A DCC can act as a hub for students to learn about the history and lived experiences of disability culture and serve as physical proof of the university’s commitment to disability justice. Advocacy for a center at Georgetown began with the leadership of Lydia X. Z. Brown (COL ’15), whose 2015 GUSA proposal gained significant momentum while they served as the undersecretary for disability affairs.

At the time, only three other universities had a DCC, and Brown’s proposal did not lead to the creation of a Georgetown DCC. Since then, five more universities, including Duke University and Stanford University, have begun planning for their own DCCs, while Syracuse University, a longtime rival of Georgetown’s, has already established a DCC. If Georgetown were to create a DCC, it would be the first Catholic university to do so.

Libbie Rifkin, special advisor for disability to the vice president of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), is hopeful the project will come to fruition. “The disabled community is highly intersectional and crosses over into every other marginalized population, so in addressing the needs of disabled students, a DCC would increase the sense of belonging felt by BIPOC, LGBTQ+, immigrant, and first generation students,” Rifkin said.

When the university went online in the spring of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, students were undeterred in their push to establish a DCC on Georgetown’s campus. In January 2021, GUSA’s Accessibility Policy Team launched a petition in favor of a DCC; as of Aug. 25, the petition had 748 signatures. The public support behind the petition has underscored the necessity for a cultural center on campus as a place for students to discuss and learn about disability culture and activism.

“The fact that Georgetown, as well as other universities, consistently overlook disabled students is the reason that we need a Disability Cultural Center,” DeRamo said.

Student activists are hopeful that the creation of a DCC will be next in a line of other institutional changes that Georgetown has made to prioritize the experience of students with disabilities. In 2017, the deans of Georgetown College announced the formation of the Disability Studies program after nearly 500 students took courses and attended events and lectures as part of a three-year Disabilities Studies Course Cluster program run by Rifkin. The announcement was preceded by a push by Danielle Zamalin (NHS ’18), then GUSA accessibility policy chair, who gathered widespread student support for the program.

The experience of disability is different for everyone, and the program can help students like Grace Crozier (COL ’21) parse through these aspects of her identity.

“Disability is an identity that I don’t always feel comfortable with but I know is always there. There’s a weird kind of privilege in being able to declare these things for myself as well, but it is something that I never really thought about until I entered the Disability Studies program and started thinking about it in a different way,” Crozier said.

Much of Crozier’s coursework in the Disability Studies program draws on the scholarship of the 1960s and 1970s, when disability scholars and activists made major strides in their push against ableist policies that view disability as an individual characteristic to be cured or fixed. D.C. was a center for disabled activism at the time, including in debates around the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which for the first time prohibited discrimination against and recognized rights for people with disabilities in federal programs. Disabled activists held demonstrations for years in D.C., protesting the act’s numerous vetoes. In the same year, the city created the first handicap parking sticker.

The district is also home to the only Deaf liberal arts university in which all programs and services are specifically designed to accommodate Deaf students, Gallaudet University. Gallaudet University acted as a fulcrum for Deaf activism for decades, like the Deaf President Now protests of the ‘70s. In the past, Georgetown has partnered with Gallaudet to form a consortium through which students can take a variety of courses, including American Sign Language I and II. Gallaudet, who hosts the program, opted to temporarily offer the course asynchronously during the pandemic.

Building on this legacy of local activism, the Georgetown administration recently expanded the scope of its disability-focused classes and programs and broadened the scope of its responsibilities to prioritize disabled students. Rifkin’s role as a special advisor was only recently created with the goal of working to strengthen the university’s commitment to disability as a dimension of diversity, an identity, and a source of community and pride, according to Rifkin.

Rifkin’s new job portfolio includes working with the Cawley Career Center to develop career resources for students with disabilities, serving on the Access and Accommodations Working Group to center the needs of disabled students in the University’s COVID-19 response, and working to ensure that Georgetown’s digital presence is accessible across a variety of domains; like launching a public awareness campaign on how to make emails and flyers and publicity more accessible.

Rifkin has been working with students from the Georgetown Disability Alliance (GDA) and the GUSA Accessibility Team to hone their message, reach out to alumni, and raise funds for a DCC. For many years, the Academic Resource Center (ARC) and other health centers have been the primary place for students with disabilities to visit to ensure their needs were met, but student dissatisfaction with that approach was high.

The current GUSA administration has supported student activism across campus. Nile Blass (COL ’22) and Nicole Sanchez (SFS ’23) won the most recent GUSA executive election with a platform advocating for strong student leadership to buoy student activism and place pressure on the university to cooperate with student demands. While the Senate is currently abolishing itself, the senators have continually worked with disabled students to create petitions and highlight places for improvement on campus.

One of the programs that GUSA has supported is the HoyaLift, which will provide ADA shuttles for students with temporary or permanent mobility disabilities beginning in the fall. The program was created by Olivia Silveri (NHS ’21) and is currently being piloted by a team of student leaders, including DeRamo, who hope that student demand for the service will be high enough to merit the university administration adopting the program.

These campaigns and programs come on the heels of about 16 months of work trying to support students with disabilities at home. Nearly three semesters of online learning has thrust the lack of intentional focus on accessibility resources available to students into the spotlight. Kiki Schmalfuss (NHS ’22), a cofounder and board member of the Georgetown Disability Alliance, has been working to support disabled students with accomodations in an online environment.

According to Schmalfuss, the challenges have been different for each student. “There have been some students who have said [the online environment] has been very positive. On the flip side, a lot of students are frustrated because the online format isn’t really conducive to how the online accommodations process has worked in the past,” she said.

When students and professors were working from home, Schmalfuss explained, the ARC was less involved in ensuring students received adequate accommodations, placing more responsibility on individual professors. Issues like accommodating longer Canvas testing times, including closed captions in recorded lectures, having certain sized text or different fonts, making a screen- reader pdf, and adding image descriptions fell onto the teachers’ shoulders. If these accommodations aren’t met, according to Schmalfuss, some students are prevented from accessing the online education space.

Many of the issues surrounding compliance with accommodations existed prior to the pandemic, but were exacerbated by the transition to online learning. To mitigate the lack of compliance with students’ accomodation and its impact on disabled students, activists like Schmalfuss have been hosting town halls and sending out surveys to the student body to ask students with disabilities what improvements should be made. Schmalfuss herself has been participating in a biweekly working group composed of faculty and students to grant students with disabilities to priority to on-campus housing (prior to the campus’s complete return to full capacity education in March) and to get access to quiet and distraction-free space near campus (an endeavour which resulted in the Georgetown-WeWork partnership).

“I really hope that Georgetown shows genuine effort and interest in hearing the needs of disabled students and actually follows up with them,” Schmalfuss said.

The Center for New Designs in Learning & Scholarship and the Office of Assessment and Decision Support also worked with the administration to streamline the accommodations process during the spring semester, implementing a “feedback loop” wherein changes to course structures were continually based on student response. The ARC itself is becoming more proactive in making professors aware of the accommodations process and checking to ensure the accommodations are upheld, and student leaders have been working with the ARC to support them in hiring disability-focused positions and working more closely with professors in meeting students’ accommodation.

These steps are promising for activists, who hope to see changes continue over the next several years. In Murphy’s view, improving accessibility on campus would not just create temporary momentum, but lasting change that affects past, present, and prospective students.

“I can guarantee that’s true for many other students, and I’m sure a lot of them have walked away from applying to Georgetown because it’s a known fact that Georgetown is physically inaccessible,” Murphy said. “If we were going to do something to change that, it would open the door to so many other students.”