Students shuffle into seats on a Tuesday afternoon, chatting as they open their bags. After a year and a half, they’re glad to see their classmates face-to-face, sit in creaky desk chairs, and hear the professor’s voice urging them to hurry up and settle in real-time. Classes at Georgetown have rejoiced in the transition back to the classroom since the beginning of the fall semester, but this classroom is unique: it’s located in the D.C. Correctional Treatment Facility, and half of the students opening their notebooks are wearing orange.

This class, Prisons and Punishment, is part of the Georgetown Prison Scholars Program, a credit-bearing program for people incarcerated in the D.C. jail, and is the only class of three offered this semester to also have a cohort of full-time Georgetown students. For the “inside students,” as incarcerated students are referred to by the program’s team, getting back into the classroom after the pandemic is incredibly meaningful.

Marc Howard, the Director of the Prisons and Justice Initiative (PJI) and the teacher of the Prisons and Punishment class, said the transition back to face-to-face learning was a drastic shift, but a welcome one. According to Howard, the transition was especially sharp for his incarcerated students due to the overwhelming isolation they experienced during the pandemic.

“It’s like night and day,” Howard said. “You’re in a cell smaller than my office fitting two people, spending 23 hours a day in these cells. That’s what it was during COVID [for the students]. So now, being able to get out more, being able to go into a classroom, being able to have outside students coming in for my class to share the class together, being able to talk and be exposed to new ideas. It’s just phenomenal for them.”

According to Howard, the program’s curriculum had to be overhauled to adapt to remote learning during the pandemic, which presented many challenges throughout the year.

“We were limping through it,” Howard said. “But some prison education programs stopped completely. We didn’t. We kept going. We thought it was important to keep finding a way to deliver something.”

Joshua Miller, the program’s Director of Education, said that although the PJI could not visit the jail, maintaining some kind of connection with the students was necessary to ensure they were surviving the fears and confusions of the pandemic.

“It’s been a terrible year for incarcerated folks. Most facilities were locked down for most of the year. Their experience was as if they were in solitary confinement,” Miller said. “It was a really hard year for our students, and in the middle of all that we weren’t allowed inside.”

Unable to enter the jail for any amount of time, and because the jail has no live internet, Miller had to come up with a new way to reach his students. He would record lectures, send them to students to download onto single-use tablets, and they would watch the videos and respond to them.

The year had to be entirely asynchronous, which for Miller made the classes feel important and incredibly challenging.

“On the one hand we were like a lifeline, we were one of the only things they had to do while they were under these really horrific conditions,” he said. On the other hand, the asynchronous setup was a major strain on the students and their learning. According to Miller, the students experienced many of the same difficulties as Georgetown undergraduates, but with the added challenges of lack of live interaction online and constraints of confinement in jail cells.

“I think our students deserve a tremendous amount of credit for how hard they worked under those conditions,” Miller said. “They really inspire me for what they’ve overcome.”

Having made it to a place where it’s safe to hold in-person classes, Miller said that both he and the students were ecstatic to see each other face-to-face.

“I am overjoyed to be back in person with our students. Some of these are students who were admitted during the quarantine so I never saw them in person,” he said. “I read their writing, but when you’ve only encountered someone in their writing, and you’ve heard and read them going through this unimaginable ordeal, and then you finally get to see them in person and give them a hug, and just be like, ‘you did it, we did it, we’re on the other side.’”

The sense of joy in returning was particularly strong in Howard’s class, where incarcerated students sit side-by-side with students from Georgetown’s main campus, and both groups could share their experiences and insight.

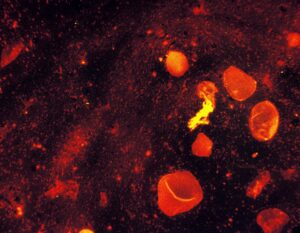

“What I said on the first day, and I’ve repeated it since, is that I want everyone to be equals in the classroom,” Howard said. “We don’t ever use the word ‘inmate.’ We call them inside students and outside students. Obviously the inside students are wearing bright orange, so it’s hard to forget that, but I try as much as possible to have that color melt away.”

Tyrone Walker, the Director of Re-entry Services for the PJI, who was once a student in the program and took Howard’s Prisons and Punishment class, said that the professors and students making the trip to share the classroom with the incarcerated students makes them feel much more valued.

“It has a huge impact to be a student on what we affectionately called the Southeast campus, and to meet all these different professors and faculty members that’s coming from the hilltop,” Walker said. “They’re coming down from the Hilltop to help, to offer a service, to show you how much they care. It looks different from that perspective. You’re a student, you just currently reside in the D.C. jail.”

For Walker, Howard’s class was more than just the standard classroom experience. They discuss topics that are personally relevant to the incarcerated students, like institutionalized racism in the criminal justice system and the history of policing.

But beyond the discussions, the class felt special because of the care Howard had for his students, Walker said.

“Professor Howard had this thing that every class he would stand at the door when we were coming in, and he would hug each and every last one of us,” Walker said. “He didn’t start class until he had hugged each and every last one of us, and talked to us individually as a person. So we bonded not just through the lens of higher education, but on a personal level. He showed us how much he cared.”

Howard said that the outside students have always made it clear that they value their classmates as well. Thais Borges (COL ’21), one of the students that visits the jail for the course, said that it feels more meaningful than a normal class to her.

“I think [the incarcerated students have] seen from us that there are people who actually do care,” Borges said. “It’s easy to say I just wanted this class for the credit, but this is not that class. We’re doing it because it’s really more than a class. We’re doing it for the experience.”

Howard said that it’s critical to the effectiveness of the class that the two groups feel equally valued. Each student needs to feel comfortable sharing their perspective and their personal stories, especially because the insight of the incarcerated students is particularly relevant to the subject matter.

“They have a lot to offer. We’re talking about prisons and punishment, it’s not a class about biology,” Howard said. “When we talk, we try to give them a chance to share their experiences, their stories, their observations.”

This opportunity for inside students to share their personal connections enriches the material for outside students, according to (Alexis) Jade Ferguson (SFS ’21), who is taking the Prisons and Punishment class.

“We read a lot of books that are focused on the racial politics of incarceration and policing,” Ferguson said. “A lot of people in the class were able to apply that theory to their own experiences. They’ve been very vulnerable in sharing why they were incarcerated, the egregious conditions of confinement that they’ve faced, the restricted mobility that they’re subject to. So the bulk of the class ends up being people sharing their experiences.”

Without the first-hand experiences the inside students share, Borges said, the class may have felt like any other reading-based class.

“There’s only so many readings you can do on a topic, especially when it has to do with people’s lives,” Borges said. “It’s great being able to sit next to the residents and hear their stories and hear what they’re advocating for, what they expect from us as students, especially coming from an elite institution.”

One of the most important opportunities the PJI offers students is a re-entry plan based on their interests, which Howard said proves the most beneficial in the long term.

To bring that benefit to more people, the PJI is establishing a new program based in a Maryland prison in which incarcerated students can get a full Georgetown education and graduate with a bachelor’s degree. The first classes will begin in January with a small cohort pulled from prisons across Maryland. The goal is to grow the program to over 100 students in its first five years, which Howard said will require much more planning and organization.

“We’ll have a Problem of God and other core courses. It’s so much more [preparation], because the credit-bearing classes, we can just kind of offer whatever,” Howard said. “But with the degree program, we have to make sure everyone’s on the pathway to a degree. We need dean-level supervision.”

As part of the supervision team, Walker said he would move first to get to know as many of the students as possible. “From the first day of class, I’ll be lining up my schedule to speak with them individually, and ensuring that these people have everything they need today to be successful tomorrow,” Walker said.

Now that classes are in-person again and the approaching official start to the full-degree program offered at Patuxent Prison, Howard is optimistic about the progress of his students and the future of the PJI. With these plans to expand further into a new state, Howard said that the distance he and the program have come since its start in 2016 continues to surprise him.

“If you had told me five and a half years ago, when we started, what we’d be doing now, I’d have said you’ve gotta be kidding me, that’s impossible,” Howard said. “But here we are doing it.”