Machinal’s set could hardly be any more simplistic. The floor and the walls are covered in basic black and white geometric shapes, vaguely reminiscent of the lighted windows of a city skyline. Stark black boxes stand in as chairs. Occasionally, a single bed frame will occupy the center stage. This reductionist backdrop is host to the emotionally fraught and morally gray story of Helen Jones.

A 1928 play by Sophie Treadwell, Machinal is Mask and Bauble’s first in-person show since the start of the pandemic. Although the theater company did virtual shows in the past, director Jameson Nowlan (SFS ’23) pushed back the premiere of Machinal from Fall 2020 to Fall 2021. In an interview with The Voice, Nowlan said, “While many productions went online, I felt with the structure of the show, with the innovative blocking and different things I wanted to do, that just wouldn’t be possible. And so I made the decision to postpone.”

Back in Poulton Hall for the first time in over a year, Mask and Bauble’s Machinal tells the story of Helen Jones (Camila Madero, COL ’23), a young stenographer struggling to accept what society expects from her as a mother and a wife. The play engages with the lofty idealism of the American Dream, and grapples with the mundane realities of pursuing it. Helen lives with her mother (Sabrina Perez, COL ‘24), for whom she begrudgingly pays the bills. Despite Helen’s exhaustion, her mother doesn’t appreciate the effort Helen makes to provide for them both. While working as a stenographer, she catches the attention of her boss (Sam Kehoe, COL ’23), who ultimately proposes to her, and she reluctantly accepts.

The opening episode of Machinal establishes the joyless thematic tone of the play. The extremely repetitive dialogue accompanied by an overbearing clicking-and-clacking sonic backdrop creates a surreal ambiance. Four of Helen’s co-workers sit on black boxes meant to imitate cubicles in an office building, each holding an antiquated technological device, like rotary phones and abacuses. They go through the motions, chanting their lines over and over again, imitating the way that workers repeat the same interaction with different customers dozens of times everyday.

True to its title, Machinal presents society as a well-oiled machine, neglecting to even refer to many characters by their actual names. For instance, George H. Jones is often called Mr. J, while many of Helen’s co-workers are nameless. This strips away another layer of individuality from the characters, reducing them to mere faces or initials. While the Mask and Bauble performance of Machinal barely deviates from the original script, its themes of existentialism and individuality transcend the period in which it was written, making the play just as engaging and relevant for a modern audience.

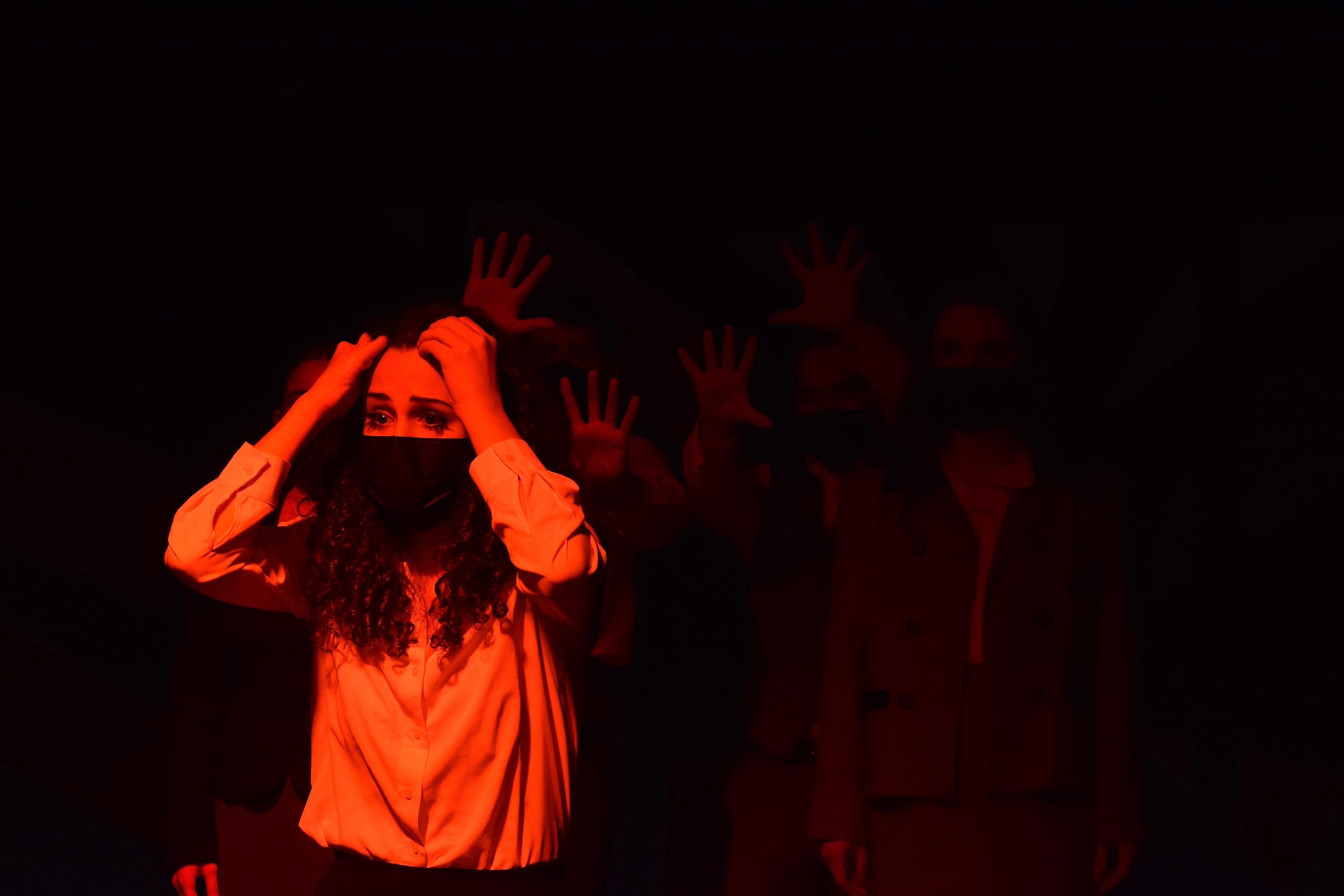

Machinal also confronts how women specifically must deal with the role they’ve been relegated to. Helen clearly does not want to be in a relationship with George H. Jones. She repeatedly asks her mom if she has to marry him, and eventually gives in because “Don’t all girls get married?” Helen and her husband are obviously not compatible; Helen is clearly impatient with his rambling, boastful stories, and she frequently shrinks away from his touch. Furthermore, her husband shows little genuine concern for her; when Helen is feeling ill after giving birth to their child, he tells her she’s got to “Brace up and face things!” His clichéd comments demonstrate his deep-rooted selfishness. In one of the most stressful moments of her life, George asks Helen to put on a cheerful facade for his benefit, without any regard for her recovery or wellbeing. After this episode, the tension in their relationship grows palpable, as their dislike for each other reaches a fever pitch by the end of the play. Helen clearly feels suffocated by societal expectations—expected to always work, be a good wife, and never need any rest—and as a result of this pressure, she becomes increasingly unhinged, suffering from hallucinations and talking to herself in fragmented rants. Although Helen is clearly not a typical, honorable hero, her plight and resistance to societal norms are portrayed in a sympathetic light, making the play an oddity for its time; one that has aged surprisingly well.

Madero’s performance as Helen is one of the strongest aspects of Machinal. She carries many of the scenes entirely on her own, often devolving into incredibly complex, disjointed rants. Madero’s rapid-fire delivery in these scenes is impeccable, not stuttering even during her most deranged monologues. The range of emotions Madero conveys is astonishing; she contrasts her intense delivery with vulnerability during her hospital stay or with giddy, childlike wonder in her scenes with her lover Richard Roe (Harrison Roth, COL ’25). These intense monologues, however, have the effect of slowing down the pace of the show. Each manic episode takes up roughly two or three minutes. When they occur so frequently throughout the show, every time Helen launches into another breakdown feels less impactful and drags out the play. Cutting one or two of these episodes would create more momentum in the play while still preserving its central themes.

Although Machinal isn’t without flaws, it’s a stunning rendition of the source material, with themes that have only grown more salient in the near century. Machinal ran in Poulton Hall until Nov. 6.