During Nile Blass’s (COL ’22) freshman year at Georgetown, students voted to establish a semesterly reconciliation fee of $27.20 per student. The money raised from the fee, about $400,000 a year, would be used to create a reconciliation fund for the descendants of the 272+ enslaved people the university sold in 1838 to keep itself financially afloat.

Blass graduated almost three months ago, and descendants say they haven’t seen a penny.

“It’s not nothing to try to acknowledge publicly that this history and people existed, because I don’t think that’s even a reality we could acknowledge [ten years ago],” she said. “But if you’re gonna do it, do it, and I don’t think Georgetown has made the decision to do it.

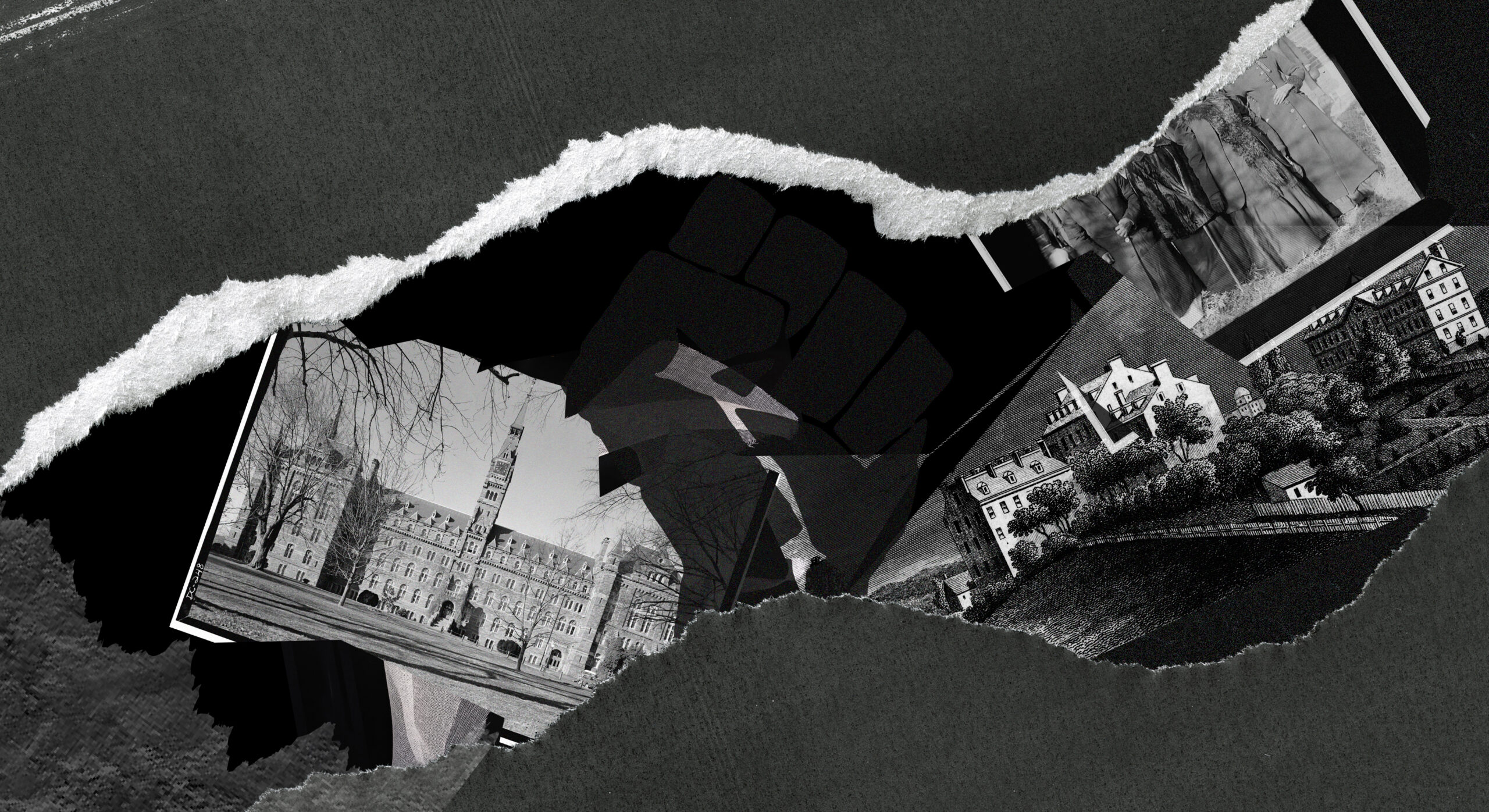

The advocacy group Blass worked with throughout her time on campus, first called Students for the GU272+ and recently renamed Hoyas Advocating for Slavery Accountability (HASA) has been the focal point of student activism addressing Georgetown’s profits from the institution of slavery. Comparable efforts have popped up at universities across the U.S., especially at elite East Coast schools that remain predominantly white institutions.

Over the last decade, many of these universities have begun publicly acknowledging how intertwined their history is with the institution of slavery. Brown was the first, releasing a 2006 Slavery and Justice Report that found that at least 30 members of Brown’s original steering committee owned or captained slave ships. Columbia University and Slavery, the product of a 2015 research-based class, revealed at least five of the first ten presidents of the New York school enslaved people. When Dartmouth was founded, “there were more slaves than faculty, administrators, or active trustees,” according to historian Craig Wilder. Slavery was embedded in every facet of these institutions, built into the lofty halls.

Along with their acknowledgments, many universities, including Georgetown, promised to do better. Universities committed to renaming buildings dedicated to enslavers, constructing memorials for the enslaved people who lived and died on university campuses, and creating scholarship programs for the descendants of those the university enslaved. But these commitments were often nebulous and action has been slow; the demands of both students and descendants themselves have quickly outpaced the steps colleges are willing to take.

“Everyone kinda has an understanding of what the 272 is now, which is entirely different from the landscape we were dealing with in 2018,” Blass said. “But what does that mean, especially when Georgetown is introducing it to prospective students as a solved issue?”

The reports are out. We know the history. What’s next?

~~~

Harvard became the most recent university to make news about its history with slavery on April 26, releasing its own version of the Brown report. The university published an initial examination of Harvard’s ties to slavery in 2011, but it was largely student-written and did not include any official recommendations. The 2022 report, with more institutional backing, revealed that Harvard leaders and staff enslaved over 70 Black and Indigenous people and that slavery was a key driver of the university’s wealth.

Unlike the first report, this one came with recommendations — seven of them. The report suggested creating a public memorial, fostering connections with descendants, and forming partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities. University President Lawrence Bacow accepted the recommendations, and the university pledged to create a fund of $100 million to implement the projects.

Cara Chang and Isabella Cho, writers at The Crimson, Harvard’s student newspaper, have covered the announcement since the report’s release. While they said that students are encouraged by the university’s commitment, questions of what reconciliation efforts will actually look like swirl. “That’s something that I think immediately a lot of students launched on to, this idea of how is Harvard going to promise to hold themselves accountable in a very public matter?” Chang said.

To Georgetown students, this question might feel eerily familiar. A few years ahead of Harvard’s reconciliation efforts, Georgetown released its own Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation report in 2016. The report found that the Jesuits of Maryland, who ran Georgetown in the early years, owned and operated plantations across the DMV region, the profits of which were dedicated to the university. Ten percent of people present on campus in the early 1800s were enslaved, and all of the earliest buildings on campus were likely built by enslaved people.

The 272+ (now believed to be over 300 people) gained early attention because of the direct link between slavery and the Georgetown that exists today. The sale by the Jesuits of Maryland and two of Georgetown’s early presidents gave the university the money it needed to keep operating, at the expense of the enslaved people and their estimated 9,000 descendants.

“You’re still benefitting from that every single day. From the building that you walk into, to the graves that you walk over, to when you graduate and have that name, ‘Georgetown University,’ you benefit from it,” Chace Chester (COL ’22), a descendant, said.

Georgetown’s report included recommendations of its own, including renaming two buildings on campus previously named after Thomas Mulledy and William McSherry, two of the men responsible for the sale of the 272+. The report also recommended that the university offers a formal apology, engages with descendants, erects a public memorial, creates an institution for the study of slavery, and invests in diversity.

The apology and renaming of the buildings to Isaac Hawkins and Annemarie Becraft Halls came quickly; memorialization and financial support remain unfulfilled goals. According to Cho, students at Harvard similarly saw an early willingness from the administration to rename campus mainstays dedicated to enslavers. Just a few days after the 2022 report was released, John Manning, the dean of Harvard Law School, announced that the distinguished Royall professorship, which was named for Isaac Royall, who at one point enslaved the most people in all of Massachusetts, would be retired. But these actions have so far been academic-focused and largely symbolic.

“Whether those will be followed in the ensuing years by financial commitments remains to be seen,” Cho said.

~~~

In 2018, Fax Victor (COL ’19), designed the first memorial for the people Georgetown enslaved. On April 26, 2022, HASA held a rally in Georgetown’s Red Square to remind students that despite the working group’s recommendation, no public memorial has been built to honor the 272+. Yet, the only on-campus physical reminder of the university’s history of slavery is a TV screen in Sellinger Lounge that displays the names of the 272 with little context. Only if students approach the screen can they read the small plaque that explains the significance of the words that cycle across the white background.

“There’s no memorialization, commemoration for these people,” Chester said.

Of the universities that have acknowledged their history with slavery, only two have built an official memorial; Brown has a partially submerged ball and chain next to their oldest campus building and the University of Virginia hosts two concentric rings, one of which is broken to represent the shackles of slavery. Other campuses, including Yale, still have buildings that boast the names of enslavers. (Georgetown, for its part, has yet to rename White-Gravenor Hall, partially named after Andrew White, one of the earliest supporters of the forced re-education of Indigenous peoples in the U.S.)

As Harvard begins to grapple with memorialization — Chang said students have created grassroots petitions to rename some buildings — HASA is fighting for a public memorial to finally be constructed at Georgetown.

This could take many forms. Chester sees an opportunity to draw inspiration from the National AIDS Memorial, a 48,000-panel quilt with squares memorializing over 125,000 people who died of HIV and AIDS. He also suggested creating gravestones for the enslaved people who were buried on campus and only found in 2014 during the construction of a new residential hall.

“There’s literally been buildings built over my family, they didn’t get gravestones, they didn’t get graves,” Chester said. “Even in their death, they had to face classism, racism.”

Julia Thomas (COL ’23), another descendant who’s led many of the HASA efforts, thinks Georgetown should create structured time for people to reflect on the university’s legacy. While a class that teaches the history of slavery at Georgetown exists, it is not mandatory, something students have already called for. This year, HASA planned a vigil on April 29, in conjunction with Georgetown Day, a university-wide celebration of the last Friday of classes. In the future, Thomas said, she would like to see a day set aside to remember the people Georgetown enslaved and potentially fundraise for other memorial projects.

“Our work to understand and respond to the persistent legacies of slavery takes many forms—our academic engagement, our efforts at public history and memorialization and our ongoing commitment to reconciliation and collaboration with Descendants,” a university spokesperson wrote in an email to the Voice. “Georgetown is committed to supporting community-based projects in partnership with Descendant communities.” They did not answer specific questions about upcoming memorialization efforts.

~~~

Of all the reconciliation efforts made by universities with histories of slavery, direct monetary reparations have been the most elusive. Only three universities, Brown, Georgetown, and UVA, have substantially looked into the possibility. UVA is required by Virginia law to make reparations through scholarships or community economic development, and both Brown and Georgetown were responding to non-binding student referenda in favor of raising money to aid descendants.

It’s not yet clear where Harvard will land on the issue of reparations — or even if the university is in contact with enough descendants to make such a policy feasible. According to Chang, university officials say they have begun the process but have not made it clear what progress they’ve made.

“Yes it’s happening, no it’s not done. Where we are on that spectrum is difficult to discern,” she said.

Connections with descendants are key to a successful reconciliation fund, a criticism students and descendants have leveraged at Georgetown for nearly four years. The idea of providing substantive financial reparations for slavery began with student pressure, culminating in the 2019 referendum, in which students approved the mandatory contribution of $27.20. Georgetown, however, declined to implement the referendum, vowing to create its own fundraising effort which would raise a similar sum of money for a reconciliation fund. This decision on its face went against the goals of the referendum to have students, who are benefitting from the university’s legacy of slavery, contribute to reconciliation, according to HASA.

“The referendum was a way for students to honor the legacy and now it’s become a charitable endeavor,” Thomas said.

To further complicate matters, Georgetown has continuously pushed back its commitment to raise and distribute the funds. The initial announcement promised that money would go out to descendants in the fall of 2020, a deadline the university missed without comment. Instead, they joined with the Jesuits and the Kellogg Foundation to create the Descendants Truth and Reconciliation Foundation, launched in 2021. Georgetown provided $1 million to create the foundation. In an interview in January of 2022, Georgetown President John DeGioia said funds had been raised and would be distributed by the end of the current semester. Descendants and activists say they have not been.

A Georgetown spokesperson said the student committee that would distribute grants began meeting in March, but declined to give any further timeline. The university did distribute $100,000 in hurricane relief to two descendant communities in Louisiana.

This approach has drawn heavy criticism from descendants. Not only do some descendants criticize the foundation’s corporate links (JP Morgan Chase advises the fund), they say that the voices of descendants were not listened to in the process. A town hall in 2021 saw over 100 descendants protesting the plan, including language in the foundation’s mission statement that implied its goal was to change the minds of prejudiced white Americans, not to monetarily empower the descendants of enslaved Black people. Descendants have been told they have to pay a fee to join the foundation. At Georgetown, they are just one tier of the three-tiered board which will decide what projects are funded. Though the timeline of the funding is still unclear, Thomas said students and faculty will also have a large voice on the board.

“I don’t think students should have the power to decide who is getting reparative justice and who is not,” she said.

The descendant community is not monolithic — no 5,000-member group is. There might never be one proposal for how to raise and distribute funds that all descendants agree with, Blass admits. “But it does feel like you should be able to find some form of consensus or segment of the demographic that is saying ‘hey we approve of this action,’ and they haven’t been able to do that,” she said.

The issue of funding is especially pressing for Thomas, who says it’s her number one priority. At the date of publication, Georgetown has not announced distributing any of the funds.

As Harvard and other schools develop their own reconciliation plans, they have the opportunity to engage descendants more meaningfully than advocates say Georgetown has. Georgetown, meanwhile, has missed yet another deadline to get money out the door, and long-term demands for descendant involvement, transparency, memorials, and divestment from the foundation.

Blass isn’t worried about the future of the movement — Thomas and other underclassmen have taken up the mantle she laid down when she crossed the stage at the end of May. But she doesn’t want the fact that Georgetown acknowledged its history to obscure the broader questions of what to do about that history, and if they fulfill promises of action.

“At some point if you’re not seeing consistent progress, what are we talking about?” she said.

Franzi Wild contributed reporting.