A familiar scene emerges at every CAB fair: Georgetown College Democrats (GUCD) tables on the left, Georgetown College Republicans (GUCR) on the right, and the Bipartisan Coalition in the middle. Given how politically active Georgetown students are, organizations that urge civil political discourse continue to attract attention especially from new students, including the Bipartisan Coalition, much of the Georgetown Institute of Politics & Public Service’s (GU Politics) programming, the now defunct Georgetown Radical Centrists, and the newly formed BridgeUSA.

Some students may be swayed by the idea that we should collaborate across the political spectrum to help lower the temperature and reduce polarization in our partisan politics. Organizations that focus on depolarization argue that we can return to the “politics of the past,” where we could all find common ground and compromises to address issues like Georgetown’s COVID policies or student loan debt relief. The key idea driving these discussion-based organizations is that politics shouldn’t be as personal as it has gotten over the last few years, and that deep down, we can always find some way to agree on many issues.

However, today’s society is not a utopia, and it’s important to realize that politics is and will always be personal—especially for marginalized communities, which is why it is necessary that we work towards progressive action instead of reduced polarization.

The bi-annual GUCD-GUCR debate hosted by the Bipartisan Coalition is just one key example of an attempt to foster political discussion with individuals on opposite ends of the spectrum. However, despite the Coalition’s best attempts, debaters and observers often leave the room with the same beliefs they had walking in, even as debate questions focus on less critical issues that aim to invite agreement from both sides, like the evergreen topics of marijuana legalization or the Jones Act. Yet, the deliberate decision to try and skirt around what the Coalition deems controversial issues—like overpolicing or voter suppression—means that these debates perpetuate the idea that we should focus less on the injustices that affect marginalized communities and instead prioritize talking about vanilla issues where everyone is nearly on the same page.

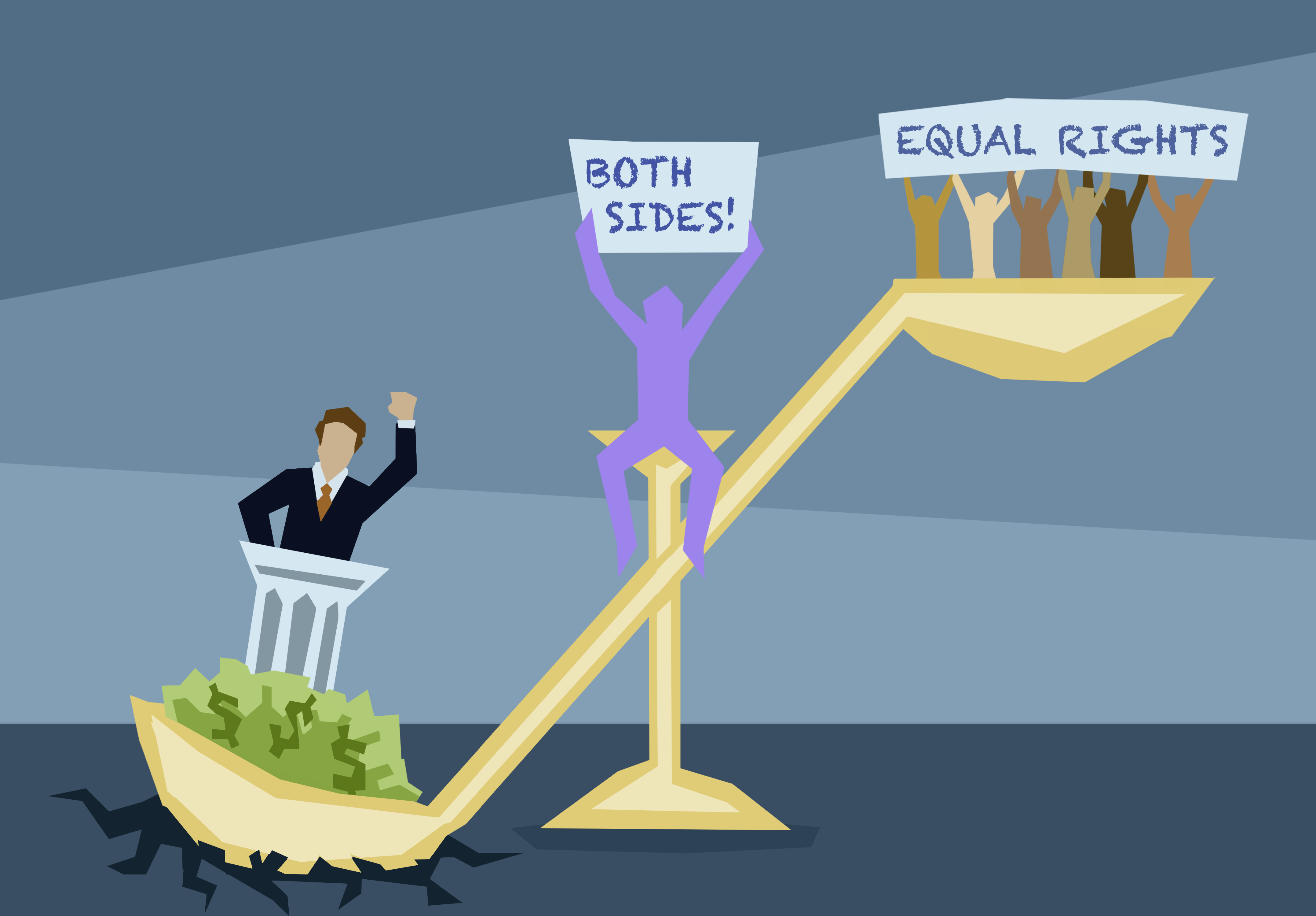

Even worse, the focus on facilitating bipartisan agreement, especially when attempting to speak on issues impacting marginalized communities, forces students of those identities to have to defend their rights and existence. On issues like LGBTQ+ rights and the right to an abortion, one court decision could be the difference between freedom or persecution, between life or death. Yet, the focus on finding common ground in politics puts everyone on an equal playing field, leaving those negatively impacted by these policies left to stand their ground against those whose lives would be completely untouched by the same legislation. The nature of depolarizing political discussion holds all opinions equal, yet we should instead be elevating the viewpoints of those most impacted by these policies.

At Georgetown, bipartisan or multipartisan discussions often include people with various identities, with one subset of people being those with privilege to the extent where they cannot imagine the effects of discriminatory legislation. For instance, on discussions of student debt forgiveness, first-generation low-income (FGLI) students may have to respond to the notion (popularized by key Republican leaders) that student loan debt relief falsely “hurts lower income families” because more debt is owned by the wealthy—despite President Biden’s plan only canceling student loan debt for those with an annual household income of less than $125,000.

Another common argument against forgiveness is that it is unfair to those “who followed the rules,” even when this viewpoint might be coming from other students who have the privilege of having family members in college. Yet, if FGLI students come to this discussion, they then have to hear out the narrative that they can pull themselves up by their bootstraps and follow the rules like everyone else, a narrative that ignores the institutional barriers they continue to face on a day-to-day basis.

Another key example is the Floridian “Don’t Say Gay” bill brought up at last year’s Bipartisan Coalition debate, which prevents teachers from including any classroom instruction that mentions LGBTQ+ individuals. Yet, these discussions force members of the LGBTQ+ community to listen to discourse where Republicans believe their identity violates America’s so-called family values. Ultimately, bipartisan discussions force marginalized communities to have to endure rhetoric that dehumanizes their identity, and even when common ground may be found, they are half-hearted band-aids to the huge bullet-hole problems that these communities are facing.

That’s why we need meaningful action—progressive action—to address the critical issues that harm marginalized communities today. From Senate Republicans proposing a national 15-week abortion ban to local school boards across the country fighting to ban books that include LGBTQ+ characters or a mention of police brutality, focusing energy on trying to work with folks who share a partisan label with extremists is a waste of time. Attempting civil discourse is just one form of dragging our feet on addressing the persistent injustices in our society. Talking to the other side is not enough to achieve equality and social justice; we need action.

For this midterm election and every election afterwards, it is critical that we invest time into passing progressive policies and elect folks who will take action for marginalized communities. This form of action could be done in so many ways, from making sure you’ve requested your absentee ballot to helping make calls in a competitive district or knocking doors with a few of your progressive friends.

Another prime example is that Virginia’s right to abortion rests on a one seat Virginia Senate Democratic majority (with a Republican House and Governor); Georgetown students can and should channel their energy towards ensuring a strict abortion ban doesn’t emerge across the Potomac in the 2023 election. Channeling political interest into something that produces real results—like knocking 50 doors or making 100 calls for a progressive candidate—is a much better use of time towards tackling injustice than the often nonstop desire for bipartisan discussion on campus.

For too long, we’ve heard that our politicians are stuck in gridlock and can’t get things done—especially for marginalized communities. Yet the solution to taking action for these communities is not focusing on the ideal of depolarization and trying to moderate our politicians. Instead, as active members of our communities both here in D.C. and at home, the solution is showing our representatives directly that we want action. By organizing to elect strong candidates who will advocate for progressive issues, we can overcome today’s gridlock and send a message that we will no longer tolerate delays in justice, helping make an impact for marginalized communities in the long run.