In 2021, Kool-Aid signed Alabama student athlete Ga’Quincy “Kool-Aid” McKinstry to promote their brand on the football field. It’s normal for athletes to market their public image, but until recently, college players were banned from doing so.

The NCAA authorized student athletes to profit from their Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) on July 1, 2021, after pressure from state legislatures and a slew of court cases, including NCAA v. Alston. This opened the door for college athletes to pursue the type of lucrative sponsorship deals their professional counterparts enjoy. Now, business opportunities for athletes are shaping the fabric of collegiate sports.

NIL deals are uncharted waters as they grow more popular. As of July, Alabama football players combined for over $3 million in revenue. The University of Colorado’s Tommy Brown models underwear for Shinesty. Even high schooler Bronny James (son of LeBron James) signed a deal with Nike. And students committing to schools are starting to follow the money.

From ‘nil’ NIL deals to a million of them

Prior to the rule change, the NCAA operated on the principle of “amateurism,” barring athletes from being paid for their play and limiting compensation to educational scholarships.

While these scholarships made education more accessible, there were still glaring issues with college amateurism—like players’ likenesses being used without their consent while they struggled financially. During the 2013-14 college basketball season, UConn star player Shabazz Napier reported that he went hungry before games because, without compensation, he could not afford to eat.

Partially due to their previously exclusive ownership of athletes’ images, the NCAA earns roughly $1 billion in revenue annually. Athletes prior to the change only got some fraction of their tuition paid, despite the vast business empire dependent on their labor.

The last three years, the NCAA faced increasing pressure to drop amateurism after a series of legal actions. California was the first to pass an NIL bill, but the real haymaker came when the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in NCAA vs. Alston that the association violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by limiting student compensation. Soon after, the NCAA reversed its rule and began permitting students to profit from advertisements.

Building momentum

With the restrictions gone, thousands of companies rushed to sign students to NIL deals. PetSmart sponsored Arkansas wide receiver Trey Knox—and his dog Blue—the same day the rule took effect. Players at top athletic programs could earn, on average, $16,000 annually.

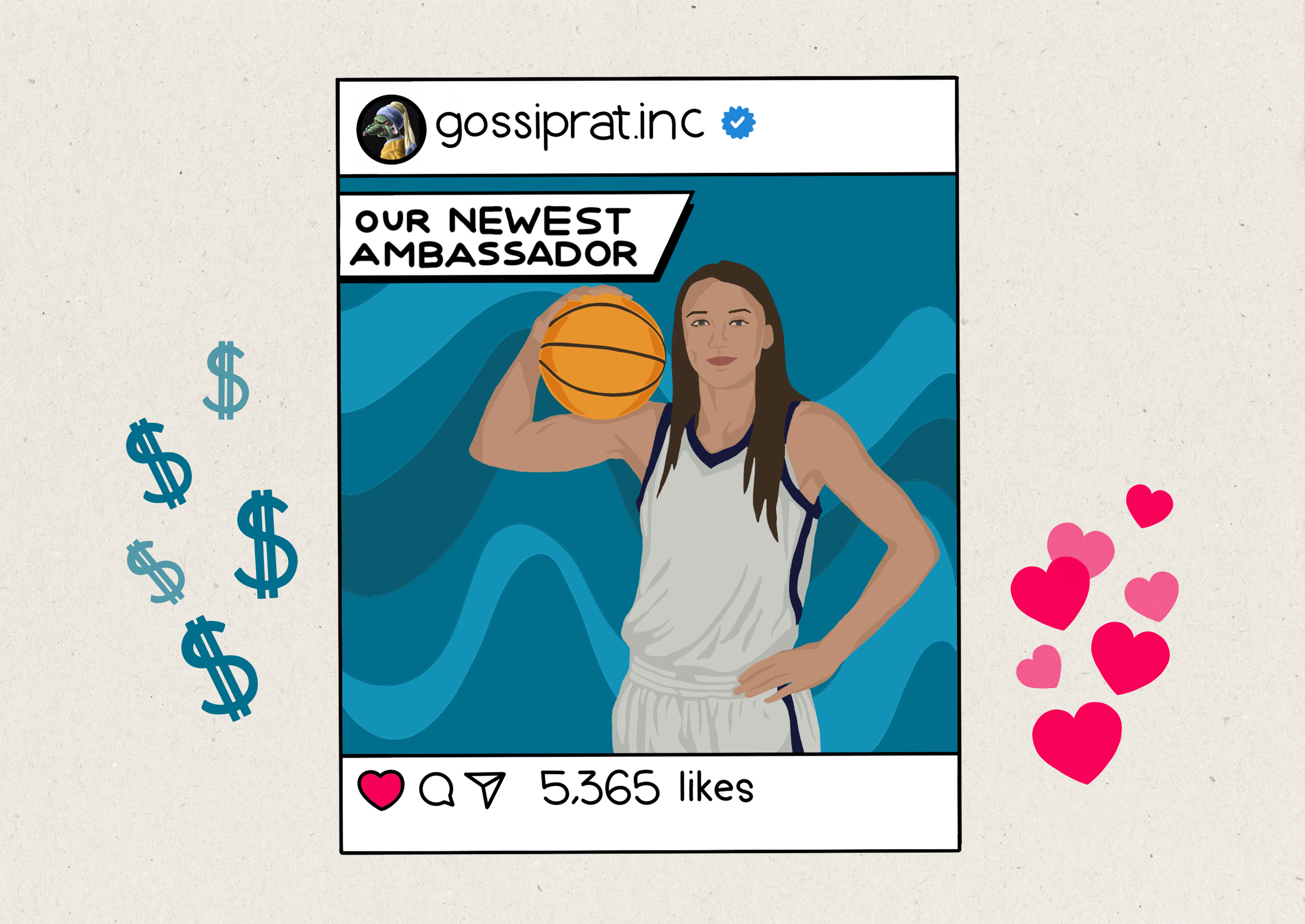

No longer confined, some players became micro-influencers after sensational performances. After leading St. Peter’s to the Elite Eight of the college basketball tournament, then-junior Doug Edert’s social media presence skyrocketed. He parlayed that fame into a deal with Buffalo Wild Wings, posting a picture of himself eating an ungodly amount of chicken.

Small business owners also benefit from NIL deals, especially in tight-knit college towns. Sassy’s Red House—a BBQ joint in Fayetteville, Arkansas—was quick to sign University of Arkansas players. Their goal is to attract more Razorback fans, boosting business that dwindled during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of course, businesses like this already profited from the gameday rush, but now players earn a share too.

The types of responsibilities given to athletes vary from deal to deal. Like Edert, some athletes simply post pictures of themselves promoting a product. Other athletes become part of the advertisements produced by the companies they represent. A local AC company’s commercial went viral, as it starred Nebraska wide receiver Decoldest Crawford proclaiming, “I’m always Decoldest!”

While not technically allowed to be part of the recruitment process for student athletes, NIL deals are influencing where players commit to. Whereas before NIL, scholarship amount could be a major factor in determining where athletes signed, prospective students can now worry less about affordability when landing deals can help them pay tuition on their own. The tuition of all BYU football players, for example, is paid for by deals with Built Protein Bars. Established promotions with certain schools will implicitly influence commitments, regardless of whether the school mentions it in a recruitment pitch.

Specific companies are prioritizing women’s sports to decrease gender inequality in athletics, where most women who compete earn substantially less than their male counterparts. Similar to Built, SmartyStreets will pay all female athletes at BYU $6,000 in exchange for promoting the brand. Researchers at the State University of New York in Cortland theorize female athletes’ greater presence on social media will aid in closing the pay gap that exists in professional sports.

Of course, some problems do still exist with NIL. Schools cannot provide direct compensation to students, so athletic departments must coordinate with outside agencies. This can drive a split between universities that can coordinate these deals and those without the resources to do so, which exacerbates gaps between PWIs and HBCUs, as well as between schools with varying endowments. Players going to schools with smaller markets may not have access to deals or the financial literacy to sign one. As a result, student athletes without the opportunity face the same problems their predecessors experienced before the rule change. The volatility of the NIL market leaves little room for equality, something that could be remedied if a minimum salary was set for all athletes.

NIL and Georgetown

Students struggle to sign and negotiate contracts while also maintaining their grades and practicing their sport. To this end, Georgetown partnered with Altius Sports and INFLCR to teach students how to market themselves and assist them in finding deals. This partnership founded the base for Georgetown’s “The Blueprint,” a portal that will allow Hoyas to connect to businesses and sign NIL contracts.

Student-athletes at Georgetown already have capitalized on NIL. Last year, several men’s basketball players made an appearance at Pinstripes for their Pins ‘N’ Wins event. Junior basketball player Jazmyn Harmon is an Amtrak ambassador, promoting travel spots on her TikTok and Instagram.

If trends continue, Georgetown athletes will only get more involved in NIL opportunities. Trains are just the start; expect to see Georgetown players featured in advertisements all around the city.