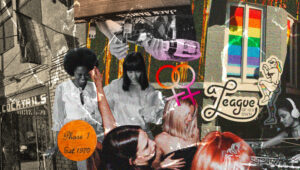

On Monday, April 24th, 2022, Georgetown’s GroupMe for queer students erupted. At first, I paid it no mind—GroupMe drama isn’t rare at Georgetown. But the sheer number of messages and the outrage that emanated from them quickly made it clear that there was something bigger happening.

Members of the Catholic Traditionalist group—Tradition, Family, and Property (TFP)—were protesting outside Georgetown’s front gates. Their anti-trans banners and fliers all featured Bible verses and various statistics that condemned “transgender ideology.”

Many of Georgetown’s queer students were quickly at the scene, mounting a counterprotest that felt like a party. Students were blasting Lil’ Nas X, waving pride flags, and dancing while the original protestors stood there with their signs and occasional chanting. As time passed, however, students began shouting at the TFP members with a megaphone and chanting at them to leave. They pushed in towards the original protestors in a clear attempt to intimidate them.

My first reaction to this counterprotest was that it didn’t seem very constructive. There was no real communication going on, no dialogue. But very quickly, I began to question that instinct of mine. Does the protest have to be constructive? What even is a constructive protest?

As a Justice and Peace Studies major, I constantly hear about protests and what they should entail. Oftentimes, a protest is considered constructive when it aims to convince the other side that you are correct. Thus, “constructive” protests are generally nonviolent and informative to the other side, with the hope that people who previously disagreed with you will come to see your cause and make concessions. If a protest doesn’t meet these goals and expectations, however, it is often written off altogether, deemed instead “unconstructive,” “unhelpful to the cause,” or in the extremes even labeled as “riots.”

This perspective, however, is problematic because it means that a protest must conform to a certain set of standards to be valuable. Adhering to these standards, set by the privileged groups who do harm in the first place, compromises the authenticity of the protest. Rather than being able to choose their own goals, protesters must try to convince others that they are right. They may even have to tweak their ideas to make them more palatable, as radical ideas are inherently not convincing to society which seeks to perpetuate itself. Thus, the movement changes to emphasize watered down solutions that would not actually lead to the change demanded by the group.

But convincing the other side is not always the primary goal of a protest. Many protests occur in order to show support for an issue. Rather than teaching the other side about their grievances or commands, these protests aim to raise awareness about the sheer number of people who are affected by an issue or support a specific cause. Such protests include the Women’s Marches after the inauguration of former President Trump. Other protests wish just to raise awareness of the existence of an issue. Instead of explaining their cause, these protests—including the widespread ones after the death of Mahsa Amini—serve as a brief introduction to the topic in hopes that people will look it up and become more informed through other causes.

Achieving these other goals should also be considered constructive. The counterprotest at the gates last April also highlights this with its goal to show solidarity. The aim there was not to convince the TFP that they were wrong, but rather to show queer students that they are not alone and that transphobic ideology is not shared by the students. And it worked—the goal was met, which should count for something when deciding whether or not a protest was constructive. Protests should be evaluated on the terms of their own goals, instead of what we deem to be an acceptable goal.

But the actual goal set by a group is not the only thing that people take into account when deciding whether or not a protest is constructive. Far more prevalent—and insidious—are the prejudices we hold against the people protesting. Take the March for Our Lives and the Black Lives Matter movement. Both movements involved mass peaceful marches after the death of many people in which the anger of the participants was highlighted. But the racial makeup, or at least the perceived racial makeup, of the two movements was quite different. March for Our Lives put no special emphasis on race while BLM centered the voices and emotions of Black people.

When one looks at the media portrayal of the two movements, however, the Black Lives Matter protests clearly invoked more of a panic and condemnation than the March for Our Lives ones did. Society projected its fear of Black anger onto the protest, thus pegging it as aggressive and unconstructive. Commonly perpetuated stereotypes then stand in the way of listening to the people we have actively oppressed for so long. By labeling a protest as unconstructive, people perpetuate these stereotypes and fear mongering in order to preserve themselves from important change.

Eradicating racism in the ways demanded by the Black Lives Matter Movement is a fundamental change to the American psyche. White people on all sides of the political spectrum felt threatened, some because they are racist, others because they finally had to face their complicity with racism and their support for structures that institutionalize racism. Thus, dismissing the protests as violent and unconstructive gave people an avenue to condemn the movement and dismiss any of the efforts they were making. Our “unconstructive” label is just a front for which people can dismiss efforts for change and protect themselves from ideas that aren’t their own. Thus, it seems that the only protests that will ever be accepted are those that do not scare white people and align with their ability to protect themselves.

By writing off the protests that we see as unconstructive, we write off all protests that are not palatable. We especially ignore the protests of those we need to listen to the most: groups we have marginalized and oppressed time and time again. We need to learn that whether we perceive a protest to be constructive or not shouldn’t be what we use to listen. Even if the people protesting are making it hard to listen by taking actions we feel strange accepting, the fact that they are protesting is important. The fact that they care enough to devote time and energy to communicate their message is grounds enough for us to listen.

It’s time we come to terms with the fact that it doesn’t matter whether we think protestors are taking the right actions or communicating their message in the right way. Instead, we must put our prejudices and personal feelings aside and listen. Listen to what they have to say. Listen to what they are asking for. Listen to why so many people are willing to act. Only then can you begin to judge.

It’s time we come to terms with the fact that men cannot become women or actually be women despite all evidence to the contrary. Your use of the oft regurgitated Buzzwords Of The Wokes, privilege and authentic, betray your bias. The Catholic group was sad and flaccid. The Men Are Women crowd was fun and partying! Dancing! L’il Naz, for god’s sake! Women’s lives are being irrevocably damaged from this fantasy-based trend through the loss of scholarships to men, acting and sports awards to men or a man being declared “The First Woman To…”. For a community that demands “safe spaces” everywhere they go, why aren’t women’s lockerrooms, public bathrooms, healthcare facilities, prisons and crisis centers safe spaces for women? You know who’s not listening? You.

what