Debate is the not-so-secret major sport at Georgetown. Between Mock Trial, Model UN (GUMUN), Moot Court, and Parliamentary Debate, nearly 100 students actively participated in national and international competitions during the fall of 2022.

Given its avid participation in debate, Georgetown’s positionality as a predominantly white institution translates into the debate world. Not only are competitors overwhelmingly white men, but gender, racial, and socioeconomic inequities are rampant in debate competitions. These disparities act as systemic barriers to entry, retention, and advancement for BIPOC students and gender minorities within these organizations, who are already historically underrepresented in debate activities.

Women comprise less than 37 percent of competitors in debate, according to a 2018 survey of 25 prominent collegiate debate societies. Even fewer advance to the highest debate rounds: Only 26 percent of all tournament winners were women in the leagues of those competing societies. Debaters of color represent an even smaller fraction at just 27 percent of all debaters.

“There have been times where I have been the only woman of color head delegate in a room,” Priyanka Shingwekar (CAS ’23), conference coordinator for the Georgetown International Relations Club (IRC) and leader of GUMUN, said. “It’s incredibly hard for a woman of color to advance in a lot of leadership roles.”

Shingwekar joined GUMUN in her first year at Georgetown. Since then, she has repeatedly encountered this lack of gender diversity firsthand. One discouraging factor in attending MUN conferences, according to Shingwekar, is being surrounded by delegates that are predominantly white—and male.

“Competitions are very heavily male-dominated,” Lindsey Gradowski (CAS ’24), the president of Georgetown Parliamentary Debate, said. “We have standings for team of the year, speaker of the year, and club of the year, and you can see for speaker of the year, nine out of 10 current speakers of the year are cis men.”

Gender representation matters in these competitional spaces—not only to establish an inclusive space but also an equitable one. “There’s definitely a problem I’ve experienced with non-gender minorities discounting what I’m saying in a debate round or not taking me seriously, or getting lower speaker points,” Gradowski said.

Gradowski isn’t the only parliamentary debater who noticed this problem. “My regular debate partner, who is a cis man, in-round has said, ‘This was Lindsey’s point, please attribute this to her,’” Gradowski said. “So he has noticed and has had to work to check back on our opponents and our judges [who are] not giving me the credit for the points that I made.”

Inequities in collegiate competitions stem from a vicious combination of both blatant and implicit discrimination from judges and competitors, microaggressions, the expectation of having to code switch, and a lack of role models and mentors for women and students of color. But these are not the only equity issues facing debate.

The time and costs of traveling to tournaments—as well as the unpaid labor necessary to compete or hold leadership positions—create financial barriers, especially for historically underrepresented students.

“The main barrier to debate is class and income and stuff like that, and obviously that disproportionately affects certain groups,” Sebastian Cardena (CAS ’26), a member of Parliamentary Debate, said.

The price tag associated with academic competition—including the costs of research materials, competition fees, and travel expenses—makes debate an unsustainable or undesirable activity for students from low-income backgrounds. The success of collegiate debaters often rests on prior experience with argumentative speaking and with expensive summer debate programs, academic coaches and funding, and access to debate tournaments at the middle and high school level: Students of wealthier backgrounds are at a clear advantage.

To address these systemic barriers, students, the majority of whom have experienced inequities in debate, are spearheading initiatives to expand diversity within Georgetown’s debate organizations. Although it may be too early to conclude how effective these measures are in improving diversity in the long run, they signify the beginning of change.

The director of diversity, equity, and inclusion of the IRC, Anagha Chakravarti (SFS ’25), believes debate clubs should provide avenues for students to seek financial support. To mitigate this barrier, GUMUN is open to all students, free of tryouts or requirements of previous experience, although conferences do require an application.

GUMUN has sought to break down this barrier by providing financial support and fee waivers for student delegate fees. “Financial aid is very much a no-questions-asked type of thing,” Chakravarti said. Members of the MUN team also have access to financial support via GUMUN mutual aid, which aims to cover travel and conference expenses, and a community closet, where students have the opportunity to lend and borrow the “Western business attire” required by Model UN conferences.

Competitors have also expressed that reforming existing judging practices is key to alleviating gender and racial discrimination in debate.

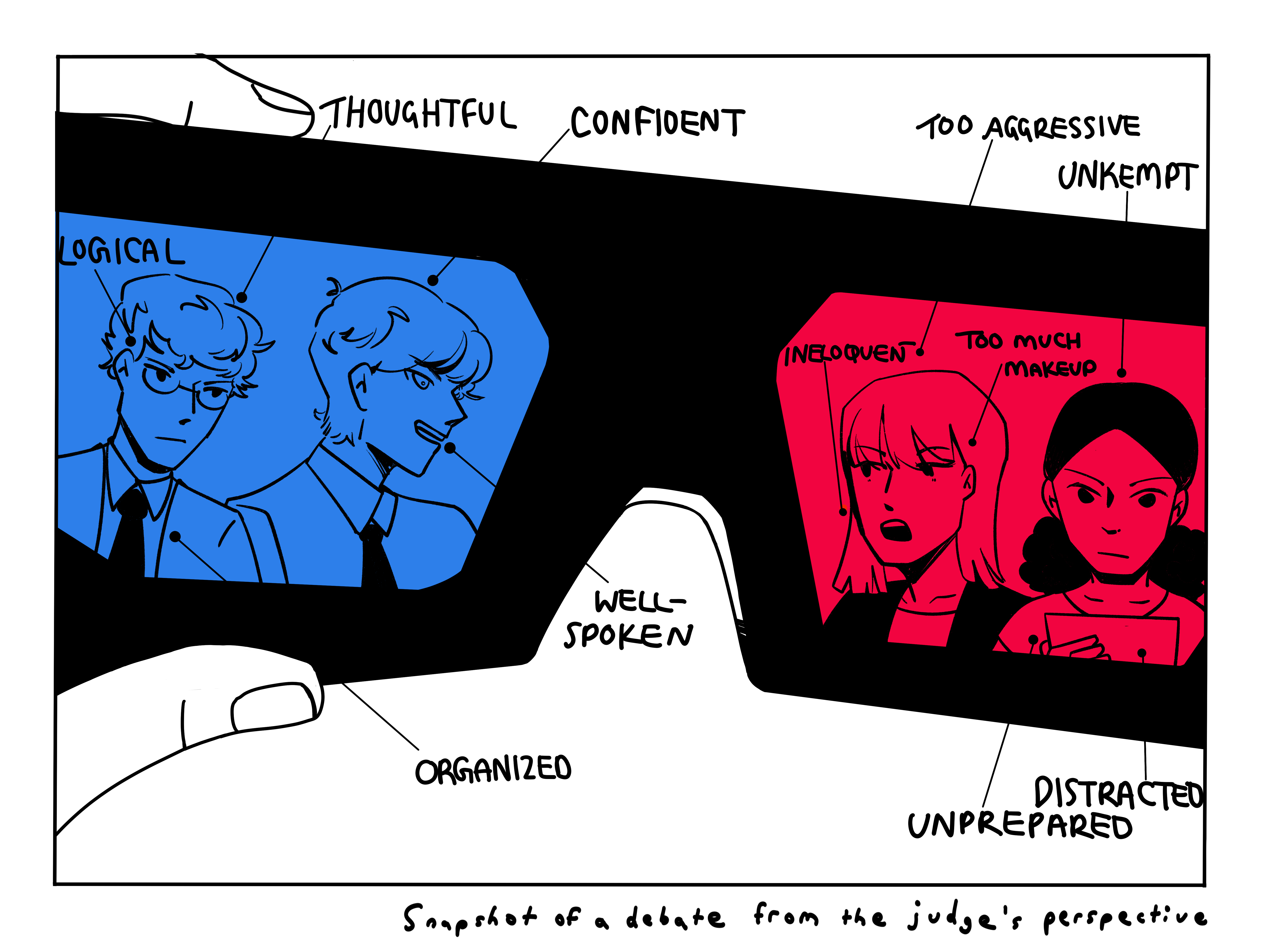

According to a study by the American Parliamentary Debate Association (APDA), non-male speakers received fewer speaker points on average than their male counterparts. Such gender biases result in unfair scoring and award allocation. The vice president of Moot Court, Eric Wang (CAS ’24), said that while his experience with Moot Court competitions has been mostly positive, he recognizes that certain biases exist within judging.

“When it comes to Moot or any other debating process, sometimes judges will have more subjective opinions on how you should look or how you should speak,” Wang said, elaborating on the disproportionate scoring impact on women and competitors of color.

Chakravarti listed speaking time as one clear example of judge bias. “A lot of the time the feedback and the complaints have to do with unequal calling-on. For example, certain people aren’t being called on or feel as though they are being talked over,” Chakravarti said.

To counter biased judging, associations like the APDA have established gender anonymizing systems for the identities and names of their competitors. But these systems are not adopted universally, and some competitors, including Cardena, doubt the effectiveness of such measures.

“[In anonymizing systems], we have profiles with names and pronouns, they don’t say who it is to at least give some sort of protection of bias in those rounds, but I do think that it’s minimal because there’s only so much you can do before it comes down to the bias of a judge,” Cardena said.

The system only provides anonymity for debaters up until the point they meet their judge, when biased judging is beyond the control of the competitors. Other competitions lack procedures for handling conference misconduct, posing a risk to the integrity of the competition and the safety of its competitors. Even organizations that have preestablished systems to address discrimination and misconduct typically only address these issues retroactively.

The APDA requires two trained equal opportunity facilitators at each Parliamentary Debate tournament to act as confidential resources for competitors in the event of misconduct. The facilitators receive training on how to offer support to competitors and handle a variety of potentially harmful situations according to Gradowski, who is the chair of the Equal Opportunity Facilitators Committee within her debate league.

“We can be a confidential resource—just to be there and help them talk through and process their feelings, help them if they want to take action, speak to the person and help them learn from the incident, or if they want us to make an announcement to the tournament as a whole,” Gradowski said.

Shingwekar noted that many, but not all, of the Model UN conferences she has attended have had bias reporting systems. “The conference will provide feedback forms, and you can choose to be anonymous or not, basically listing out the misconduct, and whether or not the delegate wants to take action,” Shingwekar said. “I think that’s a super important part, since it’s very survivor-focused.”

For GUMUN, these efforts to increase diversity and social inclusivity within Georgetown’s teams include team boards holding DEI-related conversations and meetings frequently.

“Both [IRC board and its sub-board within GUMUN] talk about DEI pretty much every single meeting. We’ve all made it a priority to put it in the center of focus because it encompasses every single thing that we do,” Shingwekar said.

GUMUN uses team-member training to help students recognize how to respond in situations of bias.

“We discuss active bystander intervention strategies—whether it’s that delegate, or a delegate from another school that’s experiencing that discrimination—how to help themselves, and how to help them,” Shingwekar said. “We go through those scenario-based situations so that delegates, whether they’re male, female, gender non-binary, it doesn’t matter, can practice active bystanding and active intervention.”

Beyond swift reactions to discrimination, recruitment and hiring play key roles in creating future diversity, as efforts to improve DEI shift demographics. Some clubs, like the Parliamentary Debate team, have tried to show their diverse clubs at Georgetown’s CAB fair, the quintessential on-campus event for gaining student interest in clubs and teams.

“At the CAB fair, they try not to put the cis-het white guys that are on the team there and make it seem more approachable,” Cardena said, noting the success of such strategies is unclear.

MUN and Mock trial have also invited Sexual Assault and Prevention Education (SAPE) trainings to their teams for the past few years. Marissa Wang (CAS ’26), a member of the Mock Trial team, was reassured by the club’s focus shift towards safety.

“The whole club had SAPE training in the beginning of the semester,” Marissa Wang said. “[The Mock Trial board] heavily emphasized that we all needed to be there because obviously member safety is really important. They take measures during club events to make sure everyone feels welcomed and comfortable.”

Despite certain clubs taking proactive steps to address sexual harassment and discrimination, these trainings aren’t mandated by the university for all clubs. When DEI becomes optional to clubs, some may not choose to implement programs to reduce barriers of entry or consciously engage in discussions of inclusivity.

The ones that continue taking initiative foresee DEI conversations remaining a central focus of their clubs, according to several Parliamentary Debate team members.

“Two of our current board members are trained equity officers (EOs), but in the future [we may] have five board members who aren’t trained,” Gradowski said. “It’s something we’ve talked about in the past, maybe having a team equity officer.”

The efforts that these teams have made to improve DEI over the past few years have not gone unnoticed. First years like Marissa Wang expressed that efforts to create an equitable culture in Georgetown debate spaces have helped her feel more welcomed—and confident—as a debater.

“Being a freshman can be a very intimidating thing, but I’ve felt extremely welcomed and very much a part of the community since day one,” Marissa Wang said.

As debate clubs implement more DEI measures, they hope to make their clubs more inclusive to historically marginalized students.

“[Our goal is] to represent Georgetown, to do justice to the school, and to do justice to the team,” Shingwekar said. “For all of our delegates that come from different backgrounds to represent Georgetown and use their voices to advocate for themselves—that’s true representation.”