Becoming a Georgetown student means learning certain names: Healy, Lauinger, White-Gravenor, Darnall. They become not only geographical stamps and second homes, but also part of the collective consciousness, a type of remembrance for notable people in Georgetown’s history.

Margaret Smallwood is one name that most students probably have never nor will ever encounter. But she’s integral to Georgetown’s existence today.

Born in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, Smallwood lived at Georgetown in the 1830s, was enslaved by the college, and married Charles Smallwood. While enslaved, her work included the intensive manual washing of students’ and Jesuits’ clothes, fundamental to the day-to-day existence of the all-white student body. She and thousands of other enslaved people kept Georgetown afloat throughout financial difficulty.

Smallwood died on April 21, 1837, at the age of 45. The last line of the House Diary entry which describes her death and burial states: “Apparuit aurora borealis per horam.” The aurora borealis appeared for an hour. The above is all the information the Georgetown Archives contain about her.

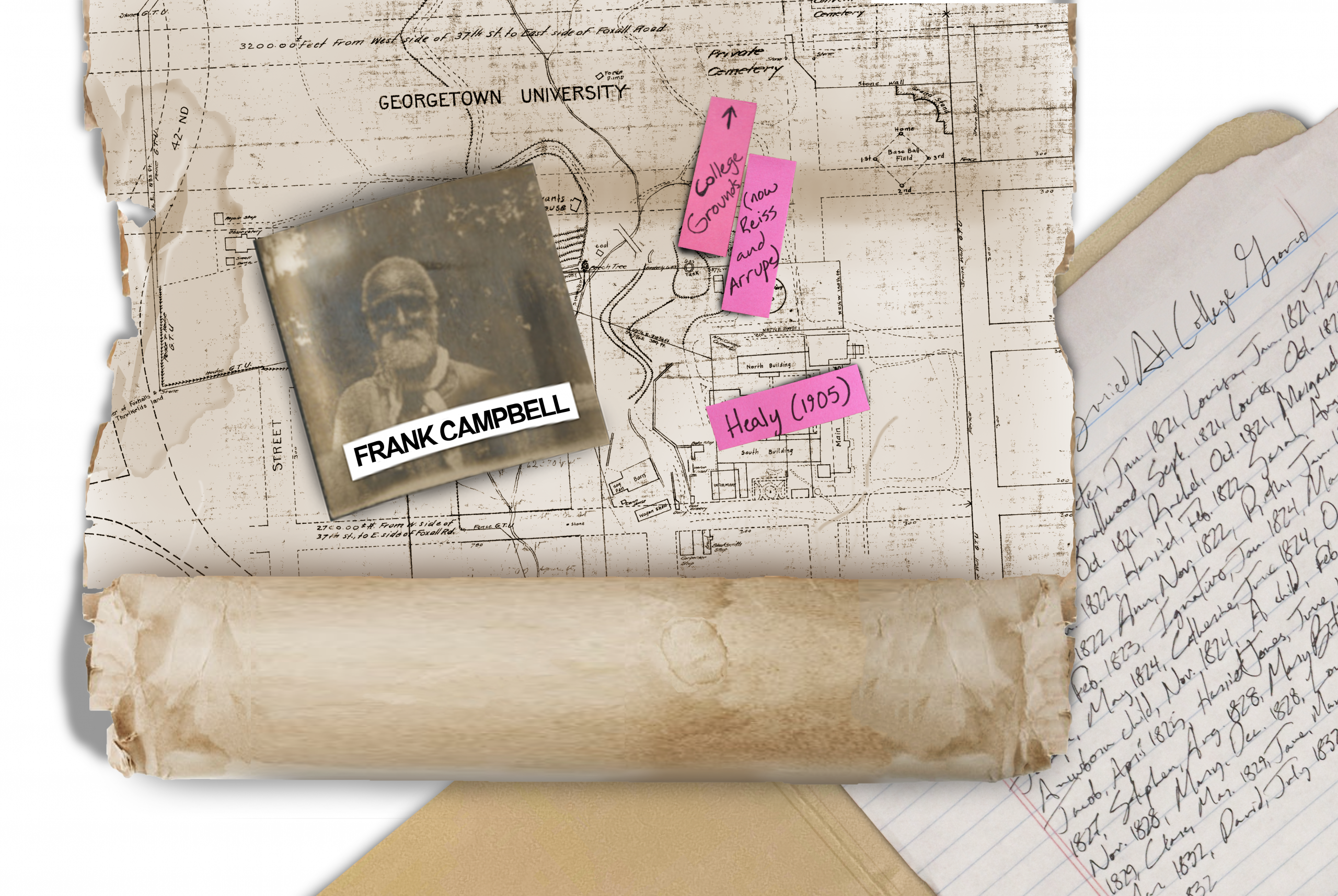

She was buried in College Ground cemetery, now located underneath the Reiss Science Building, the ICC, and Arrupe. Reiss was built in 1953 despite knowledge of the cemetery. The vast majority of remains are still underneath these buildings; a femur was discovered in 2018.

The treatment of College Ground is one distinct example of the history and people that have been erased by Georgetown. Its existence as the final resting place of the remains of many enslaved and non-enslaved people is unmarked and un-commemorated on this campus, and thus, its significance is ignored by many.

Addressing and acknowledging the university’s history of slavery is intimately intertwined with developing ways to actively memorialize the people it enslaved. Memory work is complex, and Georgetown as an institution has always been pushed to do it by students and descendants. Descendants and advocates call on students to be more proactive in the necessary memorialization and education needed to honor these people.

Not only did Georgetown rely on enslaved labor for daily operations, but the university also relied on income generated by the Jesuit slave plantations in Maryland to keep afloat. Debt incurred in the 1830s under President Rev. Thomas F. Mulledy, S.J. led to the 1838 sale of over 314 enslaved men, women, and children (the “GU272+”), to two landowners in Louisiana, netting, in today’s dollars, around $3.3 million. More than 80 percent of the 1,141 Georgetown students and alumni who enlisted in the Civil War also fought for the Confederacy and therefore the institution of slavery, and the gray in our school colors honors them to this day.

Mélisande Short-Colomb (CAS ’21) is a direct descendant of members of the GU272+. In 2017, she enrolled at Georgetown and has been involved in keeping the history of her family and others enslaved by the university alive by serving on the Board of Advisors for the Georgetown Memory Project. Now a Community Engagement Associate at the Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics, Short-Colomb is putting on a one-woman play called “Here I Am” about her families’ connection to Georgetown’s legacy of slavery.

“I came to Georgetown to bring my family and the acknowledgment of the involuntary founders of Georgetown University and the edifice of Jesuit education across America,” Short-Colomb said. “To make sure they are no longer forgotten.”

Although Georgetown has taken steps in recognizing its history with enslavement, including the recently announced reparations fund—created in response to a 2019 student referendum—many of the people central to this history remain forgotten.

“Georgetown is a predominantly white institution, and it behaves as such,” Short-Colomb said. “Everyone sees John Carroll and knows his story—one of the things to do at Georgetown before you leave is climb up in his lap and take a picture. But nobody talks about his family being a slave-owning family and a human trafficking family.”

Carroll himself owned and sold enslaved people and managed the Jesuit plantations, which were sustained with slave labor.

A lack of active memorialization and education leads enslaved people and their histories to be often overlooked by the Georgetown community, according to Adam Rothman, a professor of history who served on the 2016 Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation.

The group was convened by President John J. DeGioia to develop recommendations to acknowledge Georgetown’s history of slavery and begin dialogue around reparations—the report developed by the group included explicit recommendations on memorialization, including erecting public memorials for enslaved people and members of the GU272+ like Susan Plowden, Margaret Queen, and Harry Scott, whose names remain largely unknown due to the lack of implementation.

The GU272+ have received the majority of public attention, Rothman said. “But it is only one part of a much larger story of Georgetown’s various entanglements with slavery,” he said. “We have a lot of work to do around all the dimensions of our school history.”

Part of this work is understanding the true scale of Georgetown’s connection to slavery—the men, women, and children sold in the 1838 sale are not the only people the Jesuits enslaved. From 1650 to 1838, Georgetown and the Jesuits enslaved over 1,000 people, like Smallwood.

“We haven’t done as good of a job communicating that history in public,” Rothman said.

Student activists and descendants see the lack of memorialization as disruptive to proper engagement with Georgetown’s history. “It allows us to be able to walk around and disconnect from the campus’s legacy of slavery,” Ollie Henry (CAS ’24), an organizer with Hoyas Accounting for Slavery Accountability (HASA), said. “I think that does a disservice to everyone, that we don’t get to meaningfully engage with what it means to hold a Georgetown education and how that education has been shaped by harm over time.”

Short-Colomb added that the university only began to confront its past because of descendants like her.

“Georgetown has never and will never look for descendants. Descendants have always come to Georgetown and said this is who we are,” she said. “My reason to come to Georgetown was not to receive anything from Georgetown. Georgetown doesn’t have anything to give me.”

Other than Isaac Hawkins Hall—which was renamed in 2017 to remember Isaac Hawkins, who was enslaved and sold by Georgetown—the only physical memorial on campus is a singular screen in Sellinger displaying a rolling list of names of the 272+.

Descendants’ requests to erect memorialization projects have neither received attention nor been enacted. Associate Dean of the College Bernard Cook has been heavily involved with memorialization efforts on campus—during the pandemic, Cook met with Valerie White, who was interested in memorializing her ancestor Frank Campbell on campus.

The son of Watt and Theresa Campbell, Frank Campbell was enslaved by the Jesuits and among the people sold by Georgetown in 1838. After being sold, he survived slavery and lived to see freedom. Frank Campbell is thought to be the only person enslaved by the Jesuits of whom there remains a photograph.

According to Cook, White wanted Frank Campbell remembered at Georgetown, and the family that remembers him daily was willing to pay for it. Cook sees the lack of a memorial to Frank Campbell as an example of how Georgetown lacked will and coordination when it comes to memorialization, thus leading to institutional foot-dragging.

“We have to be able to respond to people when they come to us, especially descendants when they come to us with ideas,” Cook said.

Elsa Mendoza, a professor at Middlebury College who completed her doctorate at Georgetown in 2021, created a series of temporary memorials to honor those enslaved by Georgetown and buried at College Ground. She hung up posters displaying their names in the ICC and helped Cook create a temporary memorial by projecting the names on Red Square.

The names—which included Teresa Queen, Osborn, and Louisa Jackson—are largely unknown to the Georgetown community.

“Every student should know some of the names of the people that were enslaved on our campus,” Mendoza said. “This is what students should learn about. That is what should be recognized on our campus.”

What memorialization should look like, however, is a complicated question—one that Mendoza and Cook believe should be left up to descendants.

“You really have to be extremely respectful, extremely flexible, in this work. These people and their families have been wronged.” Cook said. “We need to acknowledge that and atone for it, and work together toward correcting the power imbalances that have been in place since slavery was the dominant American institution.”

Curriculum integration could be part of this calculus, as many descendants have previously advocated, and HASA and Henry envision a university where this history is integrated into every Georgetown classroom.

Henry pointed to the Alternative Breaks Program that takes students to Maringouin, Louisiana, to learn from and engage in service in descendant communities as an example of meaningful engagement.

“These are living people who are holding their own histories,” Henry said. “We can be learning the history from them.”

Moreover, both Henry and Short-Colomb believe being a Georgetown student is inherently tied to enslavement, making historical education especially integral. “Every student that comes to Georgetown reaps the benefit of the enslavement and trafficking of those families,” Short-Colomb said.

Rothman also believes that teaching this history is a key component of any physical memorialization on campus. “You can rename buildings until you’re blue in the face, but if there’s no teaching and no pedagogy around what all of those symbols mean, then people simply won’t know,” he said.

According to Henry, effective memorials should create space for reflection, engagement, and community. To that end, Henry and other HASA organizers are in the process of constructing a ‘living’ memorial quilt made up of the clothing of descendants and students.

For Short-Colomb, the 2019 referendum that called for a reparations fund remains a key exemplification of what effective memorialization could look like: students and descendants coming together to collectively ask the institution to redress harms.

“The referendum was a clear indication that students organized made something happen, and we’re still talking about it. That’s a memorial—the fact that we are still having conversations about,” she said.

In recent years, however, memorialization has stalled. “The committee didn’t meet during COVID and has not met since. I asked if we would meet last academic year, and we didn’t, and I’ve heard nothing about this academic year,” Cook said.

Anita Gonzalez, a professor of African American studies who leads Georgetown’s Racial Justice Institute, thinks the onus to engage in memory work and to educate themselves rests most heavily on Georgetown administrators.

“My experience with the administration is that the people doing the administrative work don’t have the knowledge set,” Gonzalez said. “It’s a circular thing. The institution can’t do more unless it knows more.”

According to Mendoza and Gonzalez, the primary obstacle to accessible education about Georgetown’s history is the historical archives themselves—the majority of which were written by the Jesuits. While oral histories exist, they are less accessible and numerous than other sources and limited to the GU272+. Georgetown has not significantly engaged in other research methodologies, according to Gonzalez, and thus the body of knowledge about the lives of enslaved people is limited.

Short-Colomb thinks that, ultimately, the only place to go for concrete information about the people Georgetown enslaved are their descendants.

“The Georgetown archives are not a good place to find out about those families. Their descendants are the place to go for that,” Short-Colomb said.

“The memory lives in the people,” Gonzalez said. “The way memories are carried in your body—it connects to folklore, oral history, songs, and dances.”

Short-Colomb believes students carry the greatest load of memory work. She places responsibility on them for preserving the passage of this history from one class to the next.

“People were enslaved and trafficked so you can come and pick up your Georgetown degree. And it wasn’t that long ago,” Short-Colomb said. “You are all gone in eight semesters and the institution knows that, but what do you leave behind when you leave Georgetown?”