Whenever people ask me what brought me to Georgetown, one of the first things that comes out of my mouth is “Madeleine Albright.” Really? People asked. Yes! I replied. On my first tour of the Hilltop, my guide described all of the amazing and influential professors at the University, casually mentioning that the first female secretary of state in the United States just so happened to be a longtime professor in the Walsh School of Foreign Service. Such news blew me away, that I could actually have a world leader and a fearless advocate for women’s rights as a professor, so much so that it was only on the promise that I could transfer into the Walsh School of Foreign Service that I actually submitted my application to Georgetown. And despite the fact that I was not on the Hilltop last spring whenever news broke of her death, I was deeply heartbroken, so sad that I, along with thousands of other students, would never get the honor to learn from this trailblazer’s wit and wisdom.

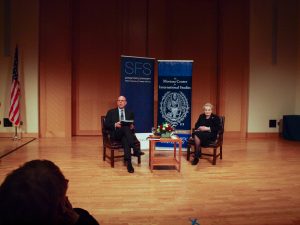

Following her death, Georgetown University released a statement declaring that “For nearly 40 years, Albright inspired SFS students not only to understand the world, but to serve the world. Generations of her students went on to do just that, a legacy that is almost incalculable in its reach.” In September of 2022, Georgetown hosted a one day symposium for Albright that included remarks from former President Bill Clinton (SFS ’68), former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield, and former foreign minister of El Salvador Mayu Ávila. Yet after the banners celebrating Albright’s legacy were taken down from the lampposts and replaced with the same old ones of Georgetown’s values, no lasting reminders of her remain on this campus. Yet if such a legacy is “incalculable,” shouldn’t there be a visible representation of that legacy? Shouldn’t Georgetown erect a permanent reminder of not only her legacy inside the classroom but outside? Luckily for Georgetown, an opportunity to do so is fast approaching. March 23rd, 2023 marks the one year anniversary of Albright’s death. Though history best remembers Albright as a pioneering politician in a previously exclusively male role, she always said, “I am sometimes known as secretary, but most of all, I like being known as professor.” Thus, Georgetown should erect a statue of Albright in order to honor her contributions to higher education at the Hilltop and global politics, and, most importantly, her advocacy for women’s and refugees’ rights.

Before continuing, it is vital to acknowledge that as a politician and as a human being, Albright was far from perfect. In fact, during her tenure as U.N. ambassador and secretary of state, she made some profoundly poor decisions that affected thousands of people around the globe. The two most notable decisions were her inactivity during the Rwandan Genocide and the infamous 60 Minutes interview where she said that “the price is worth it.” That is, the reported deaths of half a million Iraqi children due to U.S.-enforced sanctions were an unfortunate price to pay in the U.S.’s protest against Saddam Hussein invading Kuwait. While Albright did publicly apologize for both her inactivity in Rwanda and her calloused comment to the reporter, nothing validates the deaths of so many innocents nor excuses what she said.

For all of the mistakes Albright made, she was still human. She made horrendous decisions and she made courageous choices that allowed for other women and refugees to follow her footsteps to make a safer, more equitable world. People are complex and messy. Having a statue of Albright wouldn’t vindicate her words in one interview or her inactivity in one crisis. Instead, a statue of Albright would honor the positive contributions she made to society, both on and beyond the Hilltop.

In 1982, Georgetown named Albright the William H. Donner Professor of International Affairs at the Walsh School of Foreign Service. According to the Georgetown University Archives, as the head of the Women and Foreign Service Program, Albright’s job was to help women break into the highly patriarchal sphere of diplomacy. Through her famous simulations, Albright encouraged her female students to speak up and to interrupt by purposely placing them in traditionally masculine roles such as secretary of defense and, prior to 1996, secretary of state. For the next forty years, except for a break during her time in the Clinton administration, Albright was a pillar of the Hilltop community, from teaching her famous America’s National Security Toolbox class to inviting colleagues in the White House to come and speak with students. The rigor that she introduced into her courses not only shaped Georgetown into a powerhouse in terms of producing future leaders and diplomats but also helped the university gain the prestigious reputation it has today. A statue of her would be an important tribute to both the work she did politically and with her students.

While Albright had high expectations for her students, her commitment to them extended far beyond the classroom, from driving her students home in the midst of terrible weather to writing letters to a student deployed overseas years after he graduated. She cared about her students personally as well as professionally, and, according to the archives, swam regularly in Yates Field House in order to immerse herself fully in the Hilltop family. Such dedication and involvement in the Georgetown community should be celebrated by the university in more than mere words.

Yet Albright’s contributions go farther than the front gates of Georgetown. Albright served as the U.N. ambassador under Georgetown alum Bill Clinton (SFS ’68) from 1992 through the end of Clinton’s first term in ’96. During that time, she threw herself wholeheartedly into defending and preserving human and women’s rights both inside and outside of the U.S. As a refugee who immigrated to the United States herself, Albright was driven to work in politics in order to “repay the fact that I was a free person.” With this mindset, she led the Clinton administration to pursue an active and involved foreign policy, which gave her an even greater platform with regard to humanitarian crises around the globe as well as gender inequality. While Albright was criticized for her aggressive and oftentimes blunt tactics when dealing with world leaders, she broke the glass ceiling for women across the country, becoming the first female secretary of state in 1996, nominated, once again, by Bill Clinton.

In addition to Albright’s glass-smashing political roles and mentorship across the university, she also had incredibly strong connections to another late Georgetown professor who has a statue just east of the White-Gravenor Building, Dr. Jan Karski. In the archives, it’s noted that both Karski and Albright taught at the university for four decades and won the most popular professor award four years in a row, as well as the fact that Albright replaced Karski as the Mortara Distinguished Professor in the Practice of Diplomacy following his retirement. Furthermore, both had fled their homelands in Eastern Europe due to violence and war. Not only did Albright and Karski receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the same year, but Karski tried to stop the Holocaust that murdered three of Albright’s grandparents. And as antisemitic crimes continue to rise within and beyond the Hilltop and women’s rights are under attack around the globe, it’s essential that the university not only recognize the disparities both groups face and the contributions they make to society as a whole, but more importantly, make these oppressed peoples more visible among the important but imperfect people whose presence has made Georgetown what it is today.

As the one year anniversary of Dr. Albright’s death approaches, the university must commit to a visible and permanent reminder of her legacy, for words cannot capture the impact she had on both her students and world leaders across the globe. While nothing will bring back her powerful persona, erecting a statue of Albright will honor all of her achievements and accomplishments on the Hilltop and beyond. As Albright once declared, “It took me a long time to develop a voice, and now that I have it, I am not going to be silent.” Let’s help the late secretary ensure her impact isn’t, and never will be, silenced.

Ludicrous article which brings your own moral compass into question Kami. Shame.