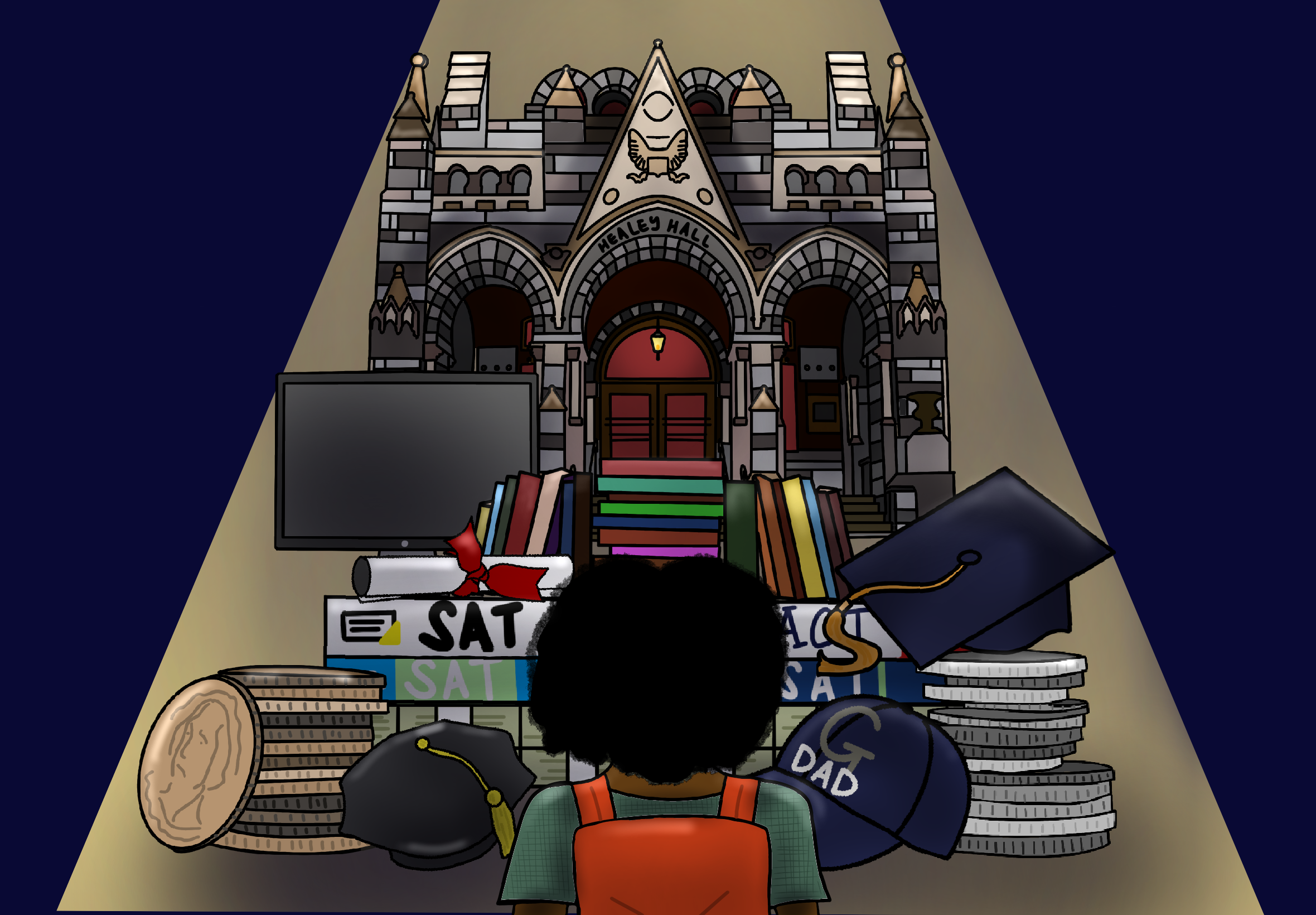

The Supreme Court’s decision to repeal race-conscious affirmative action has brought inequitable college admissions practices to the forefront of discussions on higher education. Make no mistake, however: affirmative action was never enough to mitigate racial and socioeconomic inequities within the student body. It is now more urgent than ever that Georgetown lays out a clear roadmap to rebuild its admissions process.

Georgetown’s admissions process has always been inequitable by design. Even when affirmative action was in place, Georgetown’s student body skewed overwhelmingly white and wealthy. As of 2021-22, Black and Hispanic/Latino students comprised 4.8 and 6.7 percent of Georgetown’s undergraduate student body, respectively. In the last admissions cycle, only 6 percent of accepted students were Black. This not only falls short of Dean of Admissions Charles Deacon’s goal for Black students to comprise “at least 10 percent of the student body” but, more importantly, also fails to mirror national racial demographics. On its own, affirmative action was unable to truly actualize Georgetown’s supposed commitment to diversity, especially racial diversity.

A recent report found that 60 percent of Georgetown students come from families in the top 10 percent of national incomes, whereas only 3 percent come from families in the bottom 20 percent. Ultimately, the previous affirmative action model did not curtail the high socioeconomic disparities that have persisted at Georgetown. Similar to college admissions as a whole, students who stood to gain the most from affirmative action were middle- and upper-class BIPOC students.

Simply changing one element of the admissions process will not be enough to dismantle layers of barriers faced by students of marginalized identities. Instead, the editorial board calls for a comprehensive revision of Georgetown’s admissions process at every stage, from outreach to accessibility.

From the beginning of the admissions process, first-generation low-income (FGLI) students, who are majority BIPOC at Georgetown, are systematically disadvantaged. Wealthy private high schools and schools in the Northeast and California receive better access to alumni and Georgetown admissions staff.

Georgetown needs to expand outreach to schools serving historically excluded communities, notably Title I schools, which receive federal funding to support low-income students. While the administration touts partnerships with pipeline programs and Georgetown’s own Institute for College Preparation, only a limited number of students benefit. The administration must develop and commit to a roadmap on lowering barriers for students to apply, such as specific correspondence to FGLI students and implementation of more local information sessions.

Even after students are convinced to apply, the inaccessibility of Georgetown’s application requirements poses a barrier. Especially in the aftermath of COVID, we recommend that Georgetown mirror its peer institutions and adopt permanent test-optional policies. Standardized tests tend to give white and affluent students an edge—they can generally afford prep courses and tutors, retake their exams, and can commute longer distances to test locations. As Georgetown is not on the Common Application, we further posit that Georgetown should join similar platforms like QuestBridge and Coalition for College, which target students from low-income backgrounds.

After applications are submitted, marginalized students are once again confronted with challenges. A recent study found that students from wealthy families were up to three times more likely to be admitted into Georgetown. Consequently, we assert that the admissions department must adopt socioeconomic-based affirmative action as an alternative to race-based affirmative action. While we commend President John DeGioia’s confirmation that Georgetown will pursue class-conscious affirmative action in the future in a recent interview with the Voice, the university must commit to a timeline for its immediate adoption as well as transparency for what the process will look like.

The class disparity at Georgetown is aggravated by legacy preferences for children of alumni. In 2017, legacy applicants were twice as likely to be admitted than other applicants, and the current number of legacy students at Georgetown exceeds the number of Black or Latino students. Legacy preferences, in essence, grant the wealthy an even greater head start. Deacon has argued that legacy preferences are only applied when “straddling the line” between rejection or acceptance, but if anything, such slight preferences should count in favor of FGLI students.

Moreover, Deacon alleged that ending legacy preferences would decrease alumni donations, which would, in turn, threaten Georgetown’s ability to appropriate financial aid. In 2022, however, donations accounted for just 15.1 percent of Georgetown’s operating revenue, with Georgetown still making a $235 million profit. The year before, alumni donations comprised only one-third of total donations to Georgetown; both of these undermine the aforementioned point. More importantly, studies show that legacy preferences are not linked to higher donations; Johns Hopkins reported no decline in its donation rate after scrapping legacy preference.

Deacon’s argument that continuing legacy preferences is crucial to maintaining financial aid often places Georgetown Scholars Program (GSP) students at the center of the legacy admissions debate. GSP, which works to support FGLI students, operates with a $25 million endowment from alumni donations, but the bulk of students’ scholarship money still comes from Georgetown. While GSP students receive $3,000 a year on behalf of the 1789 Scholarship through the alumni donations, students often view it as insufficient when compared to the university’s $64,896 price tag. Georgetown should allocate funding toward the 1789 Scholarship to increase its scholarship amount. Hoyas are also often offered federal loans in addition to grant money, making the decision to attend difficult when schools like University of Pennsylvania offer solely grant money free of interest rates. The university’s new “Called to Be” fundraising campaign aims to raise more than $750 million for financial aid—we commend these efforts but call on Georgetown to rethink their aid policy and work to increase scholarship and grant money, especially for GSP students.

Our calls for admissions reform aren’t new. From the SFS Academic Council’s 2020 petition advocating for many of the same reforms we are seeking to the 2023 petition to end legacy admissions, the university has time and time again been presented with solutions to the problem of equitable admissions. Students shouldn’t have to fight tooth and nail for necessary changes. The administration must immediately adopt changes in all stages of its admissions process and rebuild it from the ground up.