For 51 years, D.C. has elected its own mayor and city council to manage local affairs. But in the last five decades, residents have not settled for the limited self-government that came with so-called “home rule.” What D.C. really wants, advocates say, is to become the 51st state.

Commemorating the D.C. Home Rule Act of 1973 is a cause for both celebration and lament for activists in D.C. Home rule was a major step for the District’s autonomy—giving D.C. its first elected local government in a century—but it leaves residents far short of the rights that statehood would offer.

“Home rule is just such a watered down, wimpy goal that didn’t give us power. It certainly didn’t give us national power,” Alexa Freeman, a visiting law professor and the director of Georgetown’s Doctor of Juridical Science program, said.

Freeman was a prominent statehood activist in the 1970s and 80s. Over 40 years later, activists in D.C. are still fighting for the same goal.

Denying D.C. statehood is “undemocratic” and “rooted in racism”

“We have no say at the table when it comes to decisions that are being made for us, but not with us,” Amber Taylor, communications director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s D.C. chapter, said. “What the federal government does sometimes is not in lockstep with the values and the will of the people, and that is, frankly, undemocratic.”

D.C. has about 700,000 residents—more than Wyoming or Vermont and comparable to the population of several other states, such as Alaska and Delaware.

But unlike these states, D.C. doesn’t have voting representation in Congress. The District only has one non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives, currently Eleanor Holmes Norton, a position established by the D.C. Delegate Act of 1970. Congress also has the power to review, approve, or reject local legislation like D.C.’s budget.

“We’re hiring elected officials, or electing these officials—our council and our mayor—to make the decisions for us. It’s clear that they are not the ones who are making the decisions,” Kelsye Adams, the organizing director of D.C. Vote, a statehood advocacy organization, said.

Beyond local or District-wide issues, Adams emphasized that the lack of statehood leaves D.C. without adequate representation in national policymaking.

“It doesn’t matter if you wanted to be for reproductive rights or against it, if you wanted to be against climate change or not, if you want to legalize marijuana or not. On a federal level, you do not have representation in that conversation,” Adams said.

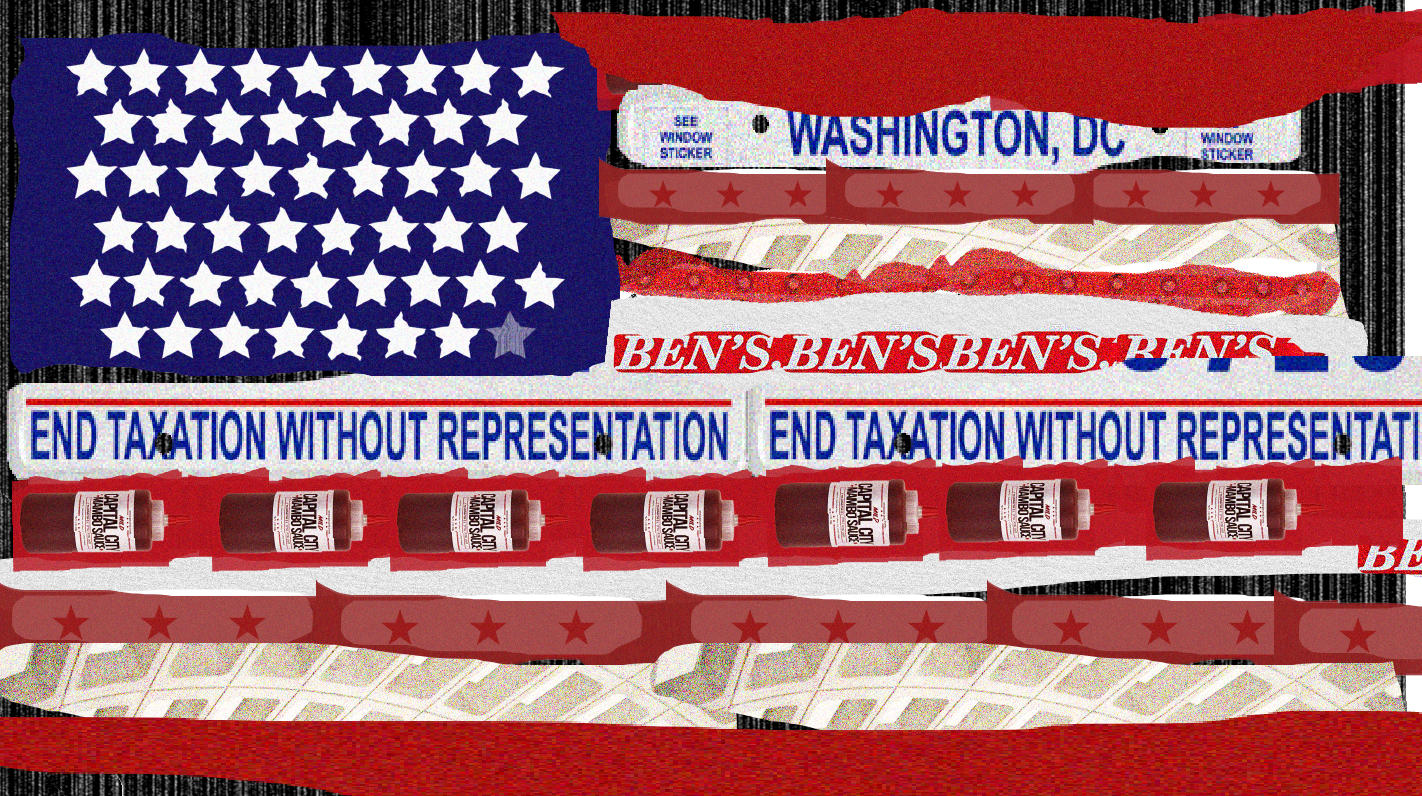

Despite the limits on D.C. residents’ political voice, those in the District pay more federal taxes per capita than any state. A slogan from the American Revolution—quoted on vehicle license plates around the District—still applies today: “End taxation without representation.”

Many activists have also said that D.C.’s lack of statehood is tied to its history as a majority Black city and attempts to disenfranchise and disempower Black residents. When the Home Rule Act was passed, D.C. was more than 70% Black, earning the District the nickname of “Chocolate City.”

“We’ve seen throughout the history of statehood folks using D.C. and the ‘Chocolate City’ of it all to deny D.C. statehood, to say that D.C. residents aren’t responsible enough,” Taylor said. “Let’s make no mistake, the denial of statehood is really rooted in racism.”

When Freeman first arrived in D.C. more than five decades ago, the city’s racial makeup was part of what made her interested in statehood activism.

“The fact that it was an overwhelmingly Black city and had no political autonomy whatsoever was just horrifying to me,” Freeman said.

Before home rule, D.C. was governed by officials appointed by the federal government, leaving the majority-Black residents of the District without an elected, representative local government.

The demographics of D.C. have shifted since the 1970s; now, only about 44% of the District’s residents are Black. Still, Freeman said, the city’s racial history and current makeup—with Black people still forming the largest racial group in the District—remains key to understanding its lack of statehood.

“Even though the city’s proportion of Black population versus white population has shifted, it is still a Black city,” Freeman said. “I have always thought that there is this deep racism among people who may not even consciously think it, but there’s this part of, ‘Well, Black people aren’t ready to really run themselves.’”

The lack of statehood impacts every issue in D.C.

Activists say that D.C.—whose residents vote overwhelmingly Democratic—lacks the final authority to set its own policies on any number of issues, including, for example, abortion.

In 2011, in an effort to avoid a government shutdown, President Obama cut a deal with congressional Republicans to bar D.C. from using its funds on abortion services for low-income women.

This deal catalyzed Josh Burch to co-found Neighbors United for D.C. Statehood, where he is now the lead organizer. Burch said that advocates were outraged that the District’s abortion protections were used as a political bargaining tool.

“It was a breaking point—we as a city, as a population, had put a lot of time and effort into supporting President Obama to become elected,” Burch said. “We didn’t expect somebody who we had overwhelmingly supported to betray us in such a way.”

Another public health issue impacted by the lack of statehood was the response to the COVID-19 pandemic—the District did not get the same aid that Congress provided to states during the crisis. The 2020 stimulus bill treated D.C. as a territory, leaving it with less than half of the funding offered to states, even though the District had more COVID cases than 19 states at the time.

“This bill cost people lives,” Taylor said. “We shouldn’t have had to play these political games for people’s lives in order to get the bare minimum and just what is expected and deserved of D.C. residents.”

Issues like abortion and pandemic response make national headlines, but the lack of statehood affects all legislative questions in D.C., big and small: Burch pointed to Congress’ attempts to prevent D.C. from banning right turns on red. This traffic law may not be the most pressing of political issues, but the surrounding debate is emblematic of the broader issue of congressional overreach in the District, according to Burch.

“No member of Congress could try to ban right on red turns in North Dakota or South Dakota. That’s a local matter that the state should have control over. But in Congress, they have control over D.C. if they want to use it, and so they try to meddle in our local affairs,” Burch said.

Beyond policymaking, the lack of D.C. statehood also shapes the way free speech activity is policed. This can impact students from Georgetown and other universities who engage in protests, according to Taylor.

“Student activism has been a really beautiful tradition in the District of Columbia,” Taylor said. “They [Congress] can absolutely have an enormous impact on curtailing first amendment rights for protesters on college campuses.”

For example, last semester, students from Georgetown and other colleges in the D.C. metro area created a Gaza solidarity encampment at George Washington (GW) University. When D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser and Metro Police Department (MPD) declined GW officials’ requests for police to clear the encampment, congressional Republicans called Bowser and MPD Chief Pamela Smith to testify before the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability a few days later.

Six Republican members of the committee also visited the encampment, where they staged a press conference, met with GW students and officials, and argued with demonstrators. Some of the representatives also shared their disgust about the encampment on social media.

The committee’s hearing was ultimately canceled after MPD violently swept the encampment hours before Bowser and Smith’s testimonies were scheduled to take place. Still, activists say that the representatives’ visit to the encampment and the call for testimony was an example of congressional overreach that pressured D.C. authorities to sweep the encampment.

“It’s unjust, paternalistic, and frankly just wasteful to subject local D.C. affairs to scrutiny by those who are not elected by the residents of Washington,” Adams said in a speech at a press conference that day. “D.C.’s elected officials must have the opportunity to truly make the decisions for the residents of D.C. They should not be bullied or forced to comply with those who are not elected by us.”

The encampment was just one example of how the lack of statehood shapes free speech in D.C., Adams said in her interview with the Voice.

Additionally, because D.C.’s court system is different from that of a state’s, the federal government has more influence over the way those who are arrested and charged—whether for protest-related charges or others—are prosecuted.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District—led by an attorney appointed by the president—prosecutes most criminal cases in the D.C. Superior Court. In the rest of the country, a state’s own attorney general, who is usually elected, holds this power.

“We are not equal partners in our criminal justice system,” Burch said. He then spoke on his own upcoming jury duty: “I’m going to stand before a judge who was confirmed by the United States Senate. I don’t have any voting representation in the Senate. I have no check or balance or oversight over who this judge is.”

Burch and others who highlight D.C.’s lack of autonomy on all sorts of issues—from abortion to right turns on red to criminal prosecution—are echoing arguments that statehood activists have been making for years.

The evolution of statehood activism since home rule

The fight for D.C. statehood has its roots in residents pushing for increased local autonomy for more than two centuries, ever since D.C. became the U.S. capital in 1800. More recently, in the 51 years since home rule, D.C. residents have tried everything from a constitutional convention to lobbying Congress to grassroots protest marches, all in an effort to make statehood a reality.

In 1980, District voters called for a constitutional convention to draft a state constitution for D.C., a process similar to what other U.S. territories have done before being admitted as states. In 1982, elected delegates from around the District gathered for the convention. Freeman was among those delegates.

The D.C. constitution they proposed was ratified by District voters later that year. Had D.C. become a state—a process that would require federal legislation or a constitutional amendment—that 1982 constitution would have governed the new state. This, of course, never happened.

Freeman said that statehood was not as popular of a cause then as it is now.

“There wasn’t the kind of unanimity at the time about statehood as the goal. There were many, many people who thought that was outlandish, unrealistic, and even that, as a city, we weren’t ready to self-govern,” she said.

Even so, the majority of residents did vote for statehood and the proposed constitution, but without a federally approved statehood measure, the new constitution never went into effect.

Almost 30 years later, as Burch was founding Neighbors United for D.C. Statehood in 2011, activists were still divided over statehood as the ultimate goal for the District, according to Burch. Some activists pushed for measures like increased congressional representation for D.C. without embracing full statehood.

“The movement itself was a bit splintered in terms of what direction we should take,” Burch said.

In the last decade, though, Burch said, activists have coalesced around statehood, in part due to the work of groups like Neighbors United.

“I think our group has helped play a role in unifying folks and saying, ‘No, if we’re going to push for something, we’re going to push for equality in statehood,’ and so the conversation about other half measures is no longer really talked about among the advocacy community,” he said.

Arriving at unity around statehood has involved extensive advocacy. According to Burch, the movement has evolved in recent years to include both greater grassroots organizing and cross-movement collaboration with activists involved in other causes.

“There’s a lot of different issue advocacy groups that have adopted statehood as part of their important issues,” Burch said. “I think that’s one component of statehood that has changed dramatically over the last decade.”

Because statehood affects every local policy issue in D.C. and the ability for D.C.’s progressive residents to influence national politics, activists across movements have recognized statehood as a key part of their efforts as well. Burch said that this has made the statehood movement more powerful.

“If statehood is just left out by itself, in isolation as its own cause, it’s not going to ever develop a constituency large enough to affect change,” Burch said. “But if it’s statehood with environmental advocates, if it’s statehood with civil rights advocates, if it’s statehood with voting rights advocates, if it’s statehood with unions and labor—all of those groups coming together to fight for statehood creates a movement for change.”

Activists have also turned to art to spread their message. Adams pointed to go-go music, a subgenre of funk music and the official music of D.C., as an example. In addition to her work with D.C. Vote, Adams is the executive director of Long Live GoGo, an organization that works to both preserve go-go music and further racial equity.

Go-go music has its roots in local Black culture and history in D.C. In recent years, go-go bands have performed at some of D.C.’s largest demonstrations and marches, such as protests against police brutality and gentrification.

“It is the intersection of politics and culture,” Adams said. “Now we’ve been able to use go-go again as the nucleus and the root of mobilizing D.C. residents, specifically around D.C. statehood.”

It’s taken decades of creative, grassroots, and cross-movement activism, but today, polling shows that the majority of likely voters across the country support statehood for the District.

What would it take to make D.C. a state?

Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D.C.’s non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives, has introduced a bill for D.C. statehood in every Congress since she assumed office in 1991.

Getting that kind of legislative action through would take national support, and Burch encouraged students to lobby their hometown representatives on the issue.

“Members of Congress need to hear from their constituents about why this is an important issue to them, because if it’s only about the people of D.C., and it’s only driven by the people of D.C., we will continue to be ignored on the issue, because we can’t vote them out, but their constituents can,” Burch said.

However, those opposed to D.C. statehood have long maintained that this change would require a constitutional amendment. Many disagree: prominent constitutional law scholars have argued that Congress has the legislative authority to grant D.C. statehood without amending the constitution.

The constitutional objection to statehood begins with the argument that, as the capital, D.C. is and must remain under federal jurisdiction. Constitutional scholars who support statehood say that Congress could sidestep this issue through legislation that defines the nation’s capital as merely including federal buildings like the Capitol, White House, and Supreme Court. Congress could then make the rest of D.C.—where residents actually live—into a new state.

There are a few other constitutional questions related to statehood, including regarding the 23rd Amendment, which empowers Congress to grant D.C. seats in the Electoral College. Scholars and lawmakers disagree on whether these questions preclude D.C. statehood.

Adams said that constitutional arguments shouldn’t be used as a barrier to progress.

“I’m also a Black, young female,” Adams said. “When the Constitution was written, I’m positive I had no rights at all, so you telling me something was unconstitutional is kind of batshit crazy.”

Even if statehood did require a constitutional amendment, activists maintain that the cause is worth it. For District residents, they say, the stakes are high, impacting every policy issue in the city.

“Lots and lots of causes that are protected by our laws in the city are at stake, and the only way to truly secure those laws and those protections is through statehood,” Freeman said.

After 224 years as the nation’s capital and 51 years with limited local autonomy, the local momentum for D.C. statehood has only grown. But, Taylor said, the movement needs support beyond the District.

“What often feels so big and overwhelming about problems that are facing our country is that they feel really insurmountable and unsolvable. This is very much a solvable problem,” Taylor said. “But we need the rest of the country to also care about statehood in order for this to become reality.”