I’m bad at activism. I acknowledge it. I read articles but don’t share them. I hear about, for example, Donald Trump’s executive order on the Dakota Access Pipeline and skim friends’ “Organize—tonight!” posts, and I scroll past, ashamed, thinking of my bag of potatoes and head of broccoli and frying pan waiting for me to assemble a solitary dinner. I participate sporadically, and, I’m sorry to say, almost exclusively, in protests related to sexual health, though I understand intersectional reproductive justice work entails fighting for a dizzying array of causes and my demonstrated support for them is inadequate.

Keeho Kang

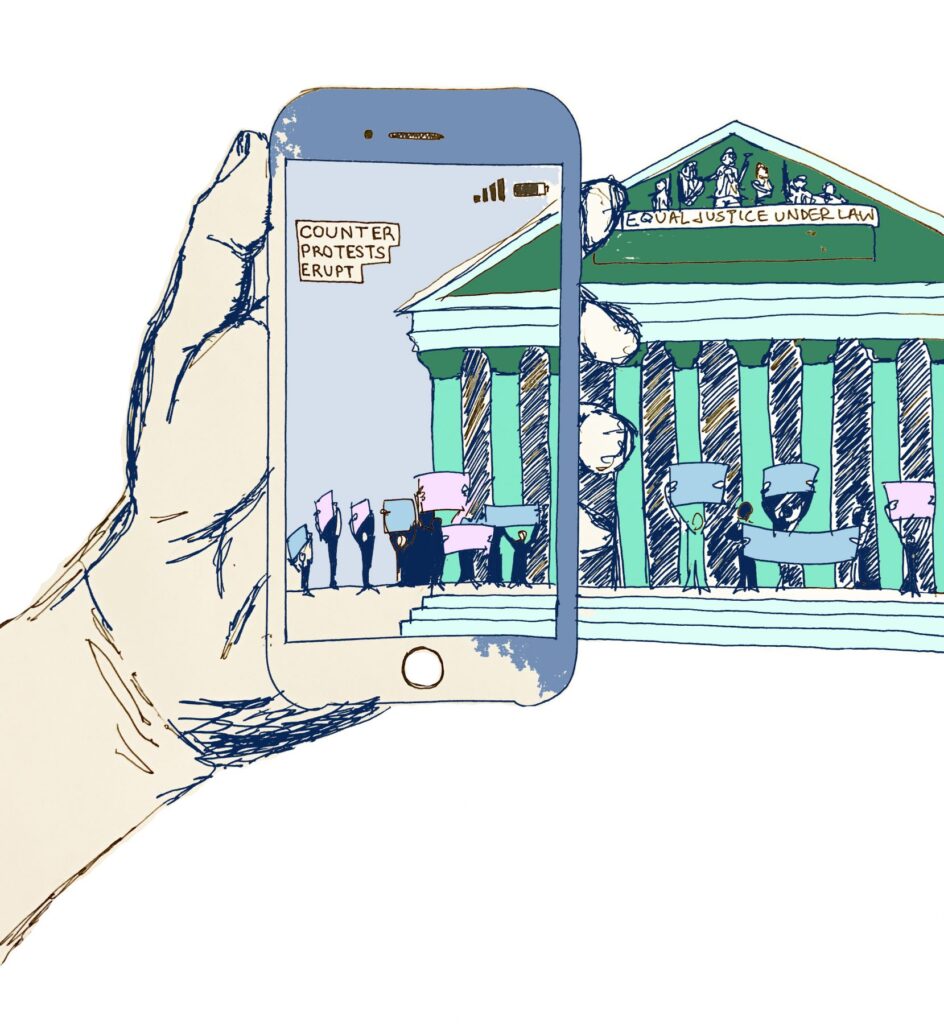

That being said, for the past three years I’ve attended the annual March for Life counter-protest outside the Supreme Court with H*yas for Choice (HFC) and the Feminist Majority Foundation. The March for Life attracts several thousand anti-abortion demonstrators to Washington, D.C. each year, but a few hundred protesters always gather outside the Supreme Court to register dissent at the anti-choice values the March for Life promotes.

Unlike my experience with maintaining the operations of HFC on Georgetown’s campus–which is met with overwhelming student support—at this protest I am in the minority, confined between the police barriers at the steps of the Court and the police barriers at the road. Some passing participants in the March sprinkled us with holy water, praying noisily in our direction. Others held up tiny dolls, intended to represent fetuses, and proffered them to us as they passed. Anti-choice demonstrators pressed in behind us, trying desperately to slip their signs in front of ours as both national press and small-scale blog operators tried to capture moments of conflict.

To some protesters, this is not a mundane, Friday morning event but rather an annual moment when the pre-1973 memories of older activists are called into sharp relief. I remember vividly watching at the 2015 March for Life as an older woman in a red-streaked white jumpsuit was carried away by several police, screaming desperately, “When abortions are illegal, women die.”

Truthfully, the experience seems absurd at times. The carefully choreographed posturing for media outlets performed by participants on both sides feels inauthentic, petty, and repetitive. Each rally shapes up similarly: pro- and anti-choice counter-protesters line up back to back and have their own chants. Both groups shoot disgusted looks and mumble comments to their compatriots when the other’s chanting becomes particularly raucous. “Pro-life, that’s a lie, you don’t care if women die” always generates raised eyebrows and a few unintelligible angry comments yelled back across the divide. Reporters vie to position themselves squarely in the middle and lead off their stories with intros like, “I’m standing here at the Supreme Court in the middle of two protests with very different ideas, and as you can see, they’re attempting to make sure their voices are heard today…”

A protest has an electric, exciting atmosphere. Even if at first you feel awkward holding your sign above your head, or you have to strain to listen to the new chant being introduced to replicate it, soon enough the vibrant energy pulsating through the air courses through you and you yell as loudly as everybody else.

And yet, it can feel as if as soon as the words leave your mouth, they disappear, swallowed by the roar of the crowd. Really, what is the point? The marble pillars of the Supreme Court and the marble exterior of the Capitol building across the street create a giant echo chamber: It’s quite unlikely a single person will change their minds. Many already agree with you; the rest—well, anybody who carries around one of those graphic and doctored images of fetuses isn’t likely to be persuaded by a sign reading “Keep Your Rosaries off My Ovaries.”

Of course, the purpose of the rally lies not in who can hear you in the moment, but in who will hear you (and hear about you) in the days that follow. There’s a reason why the empty eye of the camera lens pointing in your direction sends everyone scrambling to make sure a polished, clever, and, most importantly, pro-choice sign is front and center. Images matter. Media matters. As Ilyse Hogue, president of NARAL Pro-Choice America (previously the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws), said, “We are the majority … we know this and our opponents know this.” The man who likened abortion to the Holocaust and told me that I’m going to hell might choose to ignore objective realities, but the people reading coverage of the event from Twitter and seeing news clips the following day will likely prove more open to educating themselves. If seeing a catchy sign as the headlining photo of an article on our rally makes them click on it, read about the issue, and learn, then that’s a desirable outcome.

On the other hand, I often worry about normalization. The images coming out of this march and counter-protest, and others like it, reinforce the idea that there are two equivalent sides: two groups, spatially separated, each with megaphones and speakers and balloons, each giving interviews to press and finding their pictures and words in the papers and online. In other words, by appearing with anti-choice demonstrators, we legitimize their campaign of social and sexual control over people who need access to reproductive services.

And yet, it is too important to have a presence at these rallies to skip them because of this concern. We can work against normalization in other ways, on campus and in the other events in which we participate. This is why, for example, I follow the lead of other reproductive justice advocates and tend to refer to abortion opponents as “anti-choice” rather than “pro-life.” But the danger that exists when a reporter shows up to cover a rally and finds only anti-abortion, anti-birth control, and anti-choice vitriol awaiting them—and then writes about that in a nationally syndicated column or in an article shared by thousands on Facebook—outweighs the concern of associating with and standing by opponents of reproductive justice.

We all practice activism in other ways as well. On campus, HFC holds events and discussions, and we pass out condoms and crucial information on sexual health. As individuals or through the mechanism of an organization like HFC, we can volunteer to clinic escort or donate to local abortion funds. We can support the existence of online pharmacies that send prescription birth control or abortion pills to women in rural areas, and we can vote to ensure right-wing extremists are not elected to state legislatures or the U.S. Congress. We need to do all of this and more, but we also need to attend rallies, even if the experiences are similar and the opposition gets under our skin because these rallies are all similarly critical to attend. And to those people who, like me, mark themselves as “interested” on Facebook events but, rather than going, daydream about their dinners or watch another Netflix episode, or get started on that paper with the looming deadline: go. Drag your friends along. And then, next week, go again.

Emily is a senior in the SFS.