Content Warning: racism, depictions of assault and violence

George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police on May 25, as four officers held the unarmed man facedown on the ground, and a white officer knelt on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds.

Floyd is hardly the first to die as a result of police brutality. His death follows the murders of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black Americans at the hands of police.

In response, hundreds of thousands have gathered in cities across the United States and around the world to protest police violence and structural racism. Since the protests began, police have killed several more Black Americans, including Tony McDade and David McAtee, and injured many others with batons, rubber bullets, and tear gas. The mass protests have revolved around the call that “Black Lives Matter,” a movement that emerged in 2013 and continues to be a rallying cry for racial justice.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, weighing the risks of injury, arrest, and illness, Georgetown students across the nation have joined the protests. The Voice interviewed eight student protesters, and these are their experiences:

William Hammond (SFS ’23) – Los Angeles, California

Illustration by Deborah HanAfter marching through downtown Los Angeles for hours, the crowd was beginning to thin. It was then that William Hammond (SFS ’23) saw the smoke. Suddenly, he was running.

Illustration by Deborah HanAfter marching through downtown Los Angeles for hours, the crowd was beginning to thin. It was then that William Hammond (SFS ’23) saw the smoke. Suddenly, he was running.

“We start to see that people are running towards us, like stampeding for their lives towards us. Some of these people are running past us and saying, ‘They lit the gas station on fire, they lit the gas station on fire,’” Hammond said. “The logical mind would be like, hey, the gas station is far away from us; even if it did explode it wouldn’t harm us. But at the same time, I didn’t know if there were pipes underneath that will explode or anything like that, so I was also sort of running for my life for a good second there.”

By Hammond’s estimate, thousands of people had congregated at Pan-Pacific Park earlier on May 30 in order to protest in solidarity with the Black community.

“It felt extremely powerful, walking down these large city streets that are known to all of Los Angelenos, and screaming ‘Black Lives Matter’ and ‘ACAB’ [All Cops Are Bastards],” Hammond said.

After the scare, Hammond and other protesters returned to where they had been marching. Soon after, Hammond was on the move again, this time to avoid interacting with the police who had converged on the scene. When Hammond returned home, he turned on CNN to see that the area near where his car had been parked now looked very different: buildings were on fire and had been broken into.

“It was surreal to see that real place—we were there not even an hour ago—was in commotion, full-on commotion,” he said.

When asked about the divisiveness surrounding the property damages caused by some protests, Hammond pointed to a recent television segment he felt encapsulated the moment.

“I was watching Trevor Noah the other day, and he really put it in the perfect way,” Hammond said. “He said people, by living in a society, agree to social conditions and a social contract. And so once that social contract—as it has been for Black people by the people who are sworn to protect them—when that contract is broken, anything is justified.”

Hammond situates the last two weeks’ marches in a longer history of Black Americans protesting the violation of this social contract, a history that includes the widespread unrest that followed the 1992 beating of Black motorist Rodney King by officers in the Los Angeles Police Department.

“I believe it’s justified because of the years of torment that Black people have lived under in our country,” Hammond said of the current protests. “This is during slavery, this is after slavery, this is everything. Everything that we’ve had to endure is sort of culminating right now in this huge movement that might even surpass the Rodney King riots.”

Hammond was proud to have attended the Los Angeles protest, but when he considered returning to march again, he realized he needed to weigh the inherent danger.

“My family advised me against it due to the fact that, you know, I’m a 19-year-old Black man. Who knows what’s going to happen? And that’s just sort of the reality of what we’re living in.”

Kayla Friedland (COL ’22) – Washington D.C.

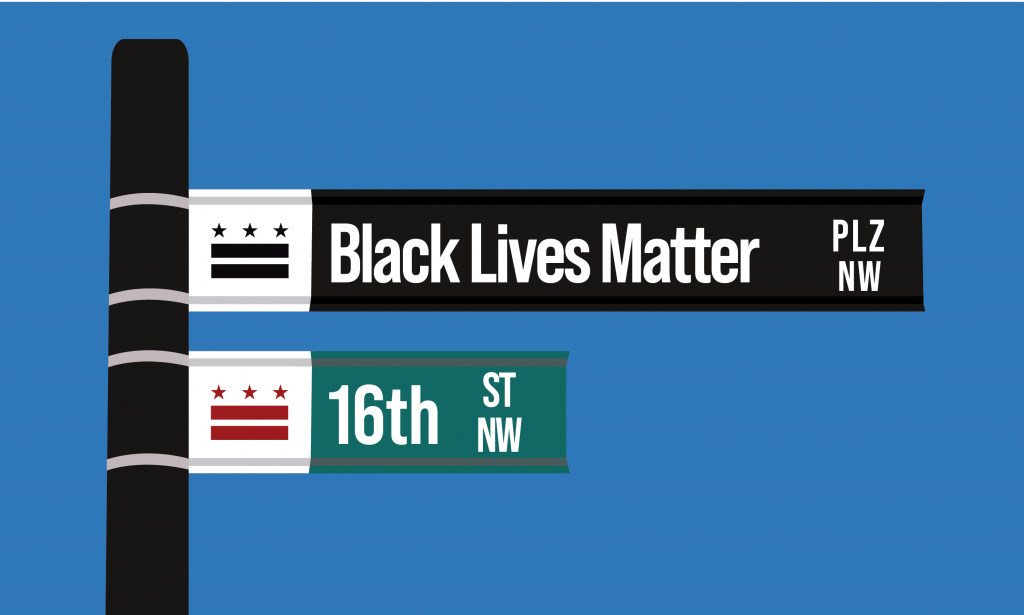

Illustration by Insha MominWhen Kayla Friedland’s (COL ’22) plane touched down in Washington, D.C. on May 26 as she arrived in the city for the summer, she already knew she would be joining the protesters assembling in Lafayette Park that afternoon.

Illustration by Insha MominWhen Kayla Friedland’s (COL ’22) plane touched down in Washington, D.C. on May 26 as she arrived in the city for the summer, she already knew she would be joining the protesters assembling in Lafayette Park that afternoon.

Friedland was surprised to observe that police, who allowed armed white protesters in several states to approach officers during protests against COVID-19 restrictions, quickly turned to violence against her and other Black protesters gathering feet away.

“I spent a lot of time that day at the front lines to help move fences between us and police,” Friedland said. “There were multiple times that night when police hit women, men, children in the face, on the body. The Secret Service fully punched a girl in the face, left her with a bruise.”

Friedland returned with her friends to the protests the next day, where the tension of the night before escalated.

“Police were starting to cut the block off with their bodies. They had batons in their hands, they had shields,” Friedland said. “Without warning, they immediately maced the person in front of them who was on a bicycle. They drove him off of his bicycle and maced him for multiple seconds, almost to make an example out of him. When I moved forward to say to them to stop, they began to mace me and I had to turn around and begin running.”

Friedland’s voice was still scratchy from the night of tear gas and mace when she explained that, as officers surrounded them and used force, some protesters began to physically resist the police. According to Friedland, two cars on the block were set on fire, and flames spread to nearby trees.

“We knew we were being boxed in, and there was nothing we could do, so people began to get violent back to take what remaining power they had and defend themselves,” she said.

As the protests continued into the night, Friedland estimates that police threw 15 canisters of tear gas into the crowd. Police also used mace, batons, striker grenades, and rubber bullets to drive the crowd back. Friedland herself was hit twice by rubber bullets during the protest.

“It turned out to be a very violent night but 100 percent not out of the choices of protesters,” she said. “I had my hands up and they shot me.”

Friday and Saturday saw some of the earliest protests following Floyd’s death, and protesters were unprepared for the level of violence they experienced from the police, she explained.

“There were countless people who could not see, whose faces were burning, who had their arms in slings because they were shot with rubber bullets,” she said. “Rubber bullets still hurt quite a lot as I can now personally attest.”

According to Friedland, it was the police, not the protesters, who instigated violence at the protests she attended. “People pushing for peaceful protest don’t understand what it is like to be on the front lines, to constantly have your bodies up for violence,” she said.

“They [the police] do not care whether people are violent or not. They care about whether they are comfortable, and as soon as they are uncomfortable, honestly just because of our presence, they hurt us just because they can.”

Christina Ruder (SFS ’23) – Dallas and Plano, Texas

Illustration by Katherine Randolph

Illustration by Katherine Randolph

“Let us leave! Let us leave!” The voices of 674 protesters carried this cry across the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge in Dallas on June 1. Christina Ruder (SFS ’23) and her fellow protesters had been surrounded by police, who had sent tear gas and rubber bullets into the crowd just minutes before. Soon after, Ruder found herself on the ground, bound by zip tie handcuffs, with no explanation as to why police were detaining her.

Ruder, who is half Ethiopian, knew her skin color posed a risk as the police tied her wrists together. “That was probably the most terrifying part of the experience, just knowing how many people have once been in that place,” Ruder said. “I knew there was no reason I should get shot, but I was still scared of making any movements. I was completely still. The people in front of me were crying. I was crying. We were all just terrified.”

She has attended three protests in recent days, including the one in Dallas, to add her voice to the growing wave of outrage against police.

Ruder, who had initially planned on going home before that night’s 7 p.m. curfew but returned when she saw the group heading to the bridge, was in the back of the crowd when the situation became chaotic.

“I see cop lights going off in the front, and then everyone starts running towards the back, and I was scared,” Ruder said. “Apparently tear gas got thrown. I was wearing glasses because I knew I could have gotten tear gassed. I usually wear contacts, and my glasses were falling. It was terrifying. Everyone was just running, and then we see we’re blocked off on the other side.”

After the protesters had all walked onto the bridge, police set up blockades in front of and behind the group, an aggressive crowd-control strategy known as kettling. The protesters kneeled and asked to leave. At first, Ruder says it seemed like protesters were allowed to go, but then Ruder and others were detained on the side of the road. According to Ruder, officers did not provide a cause.

“All these cops were just mean. That’s how I would describe them. They looked like they were enjoying us crying on the side of the highway,” she said.

Ruder and the other arrested protesters were eventually released, and no charges were filed. Ruder returned to protest two more times in her hometown of Plano. There, the protests were planned in conjunction with the police department and served more as “Cop Q&As,” according to Ruder.

“I personally talked to our police chief for 45 minutes about racial profiling and what we would do if somebody we knew was racially profiled,” Ruder said. “I really did not get a satisfying answer.”

Ruder was frustrated by the chief’s insistence that racial profiling is unrelated to physical police violence.“I was just trying to explain, it starts with these microaggressions. My friend got followed home unnecessarily with this cop’s car’s lights off. It starts with that, and ends with a man being lynched in public.”

However, Ruder also believes that conversations about racial justice should not be limited to the issues surrounding the police.

“I think the most important work is in checking your friends, checking your family, and making sure that if they say something that sounds off, you don’t just sit there passively,” Ruder said. “I think that’s where the real work is: making other people realize that this is actually an issue.”

Elizabeth Ferris (SCS ’21) – Washington, D.C.

Illustration by Allison DeRoseElizabeth Ferris’s (SCS ’21) Facebook livestream was still running as she flushed out the eyes of a protester who had just been pepper-sprayed by police. “You’re okay, you’re okay,” she repeated as she poured baking soda and water over the girl’s face. The sound of an explosion in the video’s background was immediately followed by a scream, as Ferris’s leg buckled in searing pain. Nine rounds of rubber projectiles struck her leg after a stinger grenade exploded next to her foot.

Illustration by Allison DeRoseElizabeth Ferris’s (SCS ’21) Facebook livestream was still running as she flushed out the eyes of a protester who had just been pepper-sprayed by police. “You’re okay, you’re okay,” she repeated as she poured baking soda and water over the girl’s face. The sound of an explosion in the video’s background was immediately followed by a scream, as Ferris’s leg buckled in searing pain. Nine rounds of rubber projectiles struck her leg after a stinger grenade exploded next to her foot.

Ferris was marching in a protest near 14th and H St NW in D.C. when protesters in front of her took a knee in front of police, raised their hands above their heads, and began chanting, “Hands up, don’t shoot,” a chant that has been frequently invoked since the 2014 police murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

“One or more of the officers ended up attacking a couple of the protesters and spraying at least one of them directly in the face with pepper spray,” Ferris said.

As protesters ran from the mace and tear gas, Ferris limped away from the sounds of explosions and rubber bullets as fast as she could, bloody divots dotting her leg.

Since Ferris’s injury, graphic pictures of her leg have surfaced on (Content Warning: graphic) Twitter with people both condemning her for protesting and labeling her a hero. Ferris, who is white, explained that keeping national focus on Black Americans and elevating Black voices is the most important job of white protesters, even when they face violence from the police.

“My leg just happened to be there; it could have been anyone’s leg,” Ferris said. “I only hope that it is used to leverage Black voices and that any opportunity I have to talk about what is happening is with the explicit intention of making the Black community heard.”

Ferris was shocked by the juxtaposition between armored police forces and defenseless citizen protesters.

“Police brutality is still present even in the protests, and I think you can really see that evidence by how much the police officers have by way of armor,” Ferris said. “The protesters, who are unarmed, have nothing, no body armor, no weaponry, and they are the ones who end up suffering the injuries.”

As a participant in the D.C. protests, Ferris said her main goal is to learn about how to best support the Black community. Ferris emphasized that, for her, being an ally is a process of learning from mistakes and being attentive to Black voices.

“I am not a perfect ally, I am still learning,” Ferris said. “I think being a white ally, you have to accept correction. You have to take in what someone is saying to you and just try to do better the next time to show up and be there the way people need you to show.”

During the protests, Ferris has been livestreaming on social media to combat misinformation about protests. She explained that her goal in videoing is to highlight Black voices speaking to crowds or the police rather than participate in performative activism.

“This is not political tourism, and I think some people have been treating it that way,” she said.

“There was one Black woman the other day who was upset at someone who was videotaping and said ‘This isn’t entertainment. This is literally our lives.’”

Maddy Langan (COL ’23) – Portland, Oregon

Illustration by Tim AdamiThe noise of exploding tear gas canisters, rubber bullets, and sound cannons ricocheted around the block of Portland’s Main and 3rd Streets as Maddy Langan (COL ’23) and her friends distributed packets of water bottles, socks, towels, food, and earplugs to people experiencing homelessness.

Illustration by Tim AdamiThe noise of exploding tear gas canisters, rubber bullets, and sound cannons ricocheted around the block of Portland’s Main and 3rd Streets as Maddy Langan (COL ’23) and her friends distributed packets of water bottles, socks, towels, food, and earplugs to people experiencing homelessness.

When Langan joined protests in the week following Floyd’s death, she realized that the city’s curfew and violence were having a serious impact on Portland’s homeless population, which the city of Portland estimates to be about 3,800 people. As the police turned to sound cannons to disperse crowds of protesters, Langan grew concerned about the well-being of people sleeping on downtown Portland’s blocks that police were clearing with tear gas and Long Range Acoustic Devices, which emit frequencies that can puncture a person’s eardrums at close range.

“They were tear gassing entire blocks with homeless people there and no one else,” Langan said of the Portland police. “It is just so fucking frustrating because you are tear gassing them and they have no place to go. During curfews, they said they weren’t going to arrest homeless people obviously, but that’s not stopping them from tear gassing them.”

Langan was initially apprehensive about joining the protests across downtown Portland as media reports gave her the impression of violent clashes between protesters and police. On arrival, however, she discovered hundreds of people marching peacefully into the city as a united community.

“I was expecting it to be insane, because that is all I had seen, and then I get there and it is just people marching across the bridge and asking for justice,” Langan said.

Protesters offered each other food, water, and hand sanitizer. Volunteer medics were on hand to help those tear gassed or hit by rubber bullets, according to Langan. While she appreciated the supportive community the protesters formed to help each other, Langan was disappointed that it was necessary for civilians to band together in order to defend themselves from armed officers.

“It is cool to see, but also so sad that at the end of the day everyone is there to protect each other from the police,” Langan said. “Their whole job is to protect and serve their community, but the community has to come together to protect themselves from the police.”

Although the crowd remained peaceful outside Portland’s Justice Center, violence erupted that night when the police claimed over loudspeaker that criminal activity was occurring on Main and 3rd Streets and ordered protesters to leave or be subject to force.

“We were confused because we were on Main and 3rd, but there was no criminal activity happening there,” Langan said. “People were shouting at cops and stuff, calling them pigs, but that is not illegal.”

While the crowd milled in confusion, the sound of rubber bullets firing and protesters screaming caused Langan and her friends to flee.

“Out of nowhere people are running and screaming,” she said. “They give one warning that you could not necessarily hear a block down but they are still gassing that entire block.”

Langan’s group evacuated two blocks away from the main protest to be picked up by a friend, but were pursued by a police officer who spotted them running away. Langan and her friends continued to run, and hid in a staircase when they thought the officer had lost sight of them.

“I could not understand because we were doing nothing illegal. They had no evidence we were even there, we were literally blocks away,” Langan said.

Langan believes that the importance of supporting the Black community outweighs the risks of attending protests.

“You can’t just leave it on Black people to fight for this for themselves. You need to be an ally, you need to help,” she said. “It doesn’t feel like a choice almost, not in a bad way at all. I just feel like it is the right thing to do. If you are able to go down, you should be going.”

Through the protests, Langan is learning how to elevate Black voices while reevaluating her understanding of racial issues in America as a non-Black person of color.

“I honestly thought I was really educated before this on racial issues,” she said. “I realize I have a lot to learn, and I have a lot to learn from Black people themselves. It is not my time to go there and talk obviously, but just to listen.”

Owen Johnson (COL ’22) – Washington D.C.

Illustration by Delaney CorcoranOwen Johnson (COL ’22) knew he needed to do something real to counteract the social media trends he found “shallow” and “gross.” For the D.C. native, the opportunity to express the anger and frustration that he had been feeling was only a Metro ride away.

Illustration by Delaney CorcoranOwen Johnson (COL ’22) knew he needed to do something real to counteract the social media trends he found “shallow” and “gross.” For the D.C. native, the opportunity to express the anger and frustration that he had been feeling was only a Metro ride away.

“There was no planned protest that I was aware of,” Johnson said. “I was just really angry, and I figured something would be happening at the White House.”

So, on the evening of May 31, Johnson jumped on the Red Line and headed to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., where he joined a host of protesters whose numbers grew through the night. Protesters and members of the United States Park Police and Secret Service engaged in a proxy turf war, pushing back and forth in the area in front of Lafayette Park. The Secret Service sent rubber bullets and tear gas into the crowds. Meanwhile, protesters threw mostly water bottles and some bricks, while doing their best to throw back tear gas canisters.

Images of the night were seared into Johnson’s mind. “There was a man with blood streaming down his face after getting hit on the head with a baton. You know, people screaming in pain from getting hit with tear gas.”

Johnson was hit by tear gas sent by members of the Secret Service into the middle of the crowd. Johnson says that his position as a white person gave him an opportunity to help protect his fellow protesters and ensure their voices were heard.

“Really the two things I wanted to do were to allow Black voices to be heard, and to use the fact that, in many ways, my skin color protects me from the brutality of police, to sort of use that as a shield for people who don’t have that same protection,” Johnson said.

For Johnson, attending the protest was a chance to leverage his privilege in a historic fight for justice.

“When you’re growing up and you’re reading about the Civil Rights Movement and other times of crisis in history, you always wonder where you would have been in those times. Where you would have stood, what side of the line,” Johnson said. “I just wanted to be there. It felt like a moral imperative.”

Alice Kukapa (SFS ’23) – Washington, D.C. and Montgomery County, Maryland

Illustration by Josh KleinD.C. protests are nothing new for Alice Kukapa (SFS ’23). She grew up in Montgomery County, Maryland, just a short drive away from the nation’s capital where thousands of Americans travel each year to petition for change. But marching down Constitution Ave. towards the White House, demanding justice for George Floyd, the full weight of the nationwide protests hit home.

Illustration by Josh KleinD.C. protests are nothing new for Alice Kukapa (SFS ’23). She grew up in Montgomery County, Maryland, just a short drive away from the nation’s capital where thousands of Americans travel each year to petition for change. But marching down Constitution Ave. towards the White House, demanding justice for George Floyd, the full weight of the nationwide protests hit home.

“It is really one thing, seeing these protests on TV,” Kukapa said, “Actually being there is a whole other feeling. There are a lot of emotions going on.”

On May 30, Kukapa and a group of friends took Ubers from Montgomery County to the District. They were trying to meet up at the National Archives but found their way blocked on Constitution Ave. by a large contingent of protesters. Eager to join, they exited the Uber there and began to march alongside thousands.

Kukapa was unsurprised to see the outpouring of support at the D.C. protest, but was pleased to see that these sentiments extended back home, at small-town marches throughout her suburban county. She protested in her hometown of Germantown, Maryland on June 7. While she found a different atmosphere at protests in the nation’s capital and marches in the county she grew up in, she was pleased to see her local community members driven to action outside political centers like D.C.

“These people are your neighbors,” Kukapa said. “These are people that you live with, who you see at the local shops, people who you graduated with, or went to the same schools as you. It was really nice and comforting to know that a large amount of people who grew up with essentially are in support of the cause.”

At local protests, Kukapa noticed a greater sense of leadership among younger community members. Students and young adults led the protest by teaching chants, introducing a schedule, and mapping out a route for the march.

“The leaders were pretty young, which is also super inspiring,” she said. “It was nice to see people who are my age holding the baton and running with it and able to organize.”

To Kukapa, the fight against racial injustice should not be restricted to Black communities, but requires all Americans to do their part in combating structural racism.

“I do not want to be congratulatory of white people. White people were there, which was nice. I just expect everyone to be out there on the streets because it is everyone’s problem,” Kukapa said.“I would urge people to educate themselves and realize that this is not just a Black person problem. It’s all of our problem. We all have a responsibility to stand up for injustices, and this is a grave injustice that has continued on for too long.”

Kukapa urged people to maintain the vocal activism they have demonstrated at recent protests.

“You have to keep the momentum going, and keep having these conversations and not just think ‘I protested, check off my list, that’s it,’” she said. “Speak to your family if they have racial or problematic views, speak to your friends.”

Kukapa appreciates the progress that both Black people and non-Black allies have accomplished. However, she cautions that the work is not done and protesters must not forget what and who they are fighting for.

“I am tired of the injustices that are occurring. As far as tired about protests? I am certainly not tired,” Kukapa said. “I think it is hard to get tired, especially if you are a Black person and this is your life day in and day out. You don’t get a chance to be tired.”

Olivia Cooley (COL ’23) – Boston, Massachusetts and Providence, Rhode Island

Illustration by Olivia Stevens“Black in America. The scary truth our white friend may never be able to comprehend.”

Illustration by Olivia Stevens“Black in America. The scary truth our white friend may never be able to comprehend.”

These words begin Olivia Cooley’s (COL ’23) poem, “Black in America,” which she read over Instagram as protests against police brutality spread across the nation.

Cooley has protested in Boston and Providence in the weeks since Floyd’s death. While she was initially anxious about protesting, she found the crowds offered a sense of unity and support.

“I remember being a little nervous on my way into Boston, but as the time came closer, more empowered,” she said. “There was lots of solidarity, community, and just love in the air. Everyone had a common goal, and even the cars that we were passing by were honking at us, not in anger but in support of us.”

Cooley started chants and helped others spread their own chants through the crowd to ensure that protesters’ voices were heard clearly.

“I was a cheerleader for eight years, so I know how to dig my voice out from the bottom of my heart and belt it,” she said. “It came in handy in the protests in trying to get our voices across, because that is really the true point of what we are trying to do: get our voices across.”

“Endless forms of oppression that doesn’t seem to stop. 1865, ‘emancipation.’ Slavery took on a different phase: mass incarceration, police brutality, war on drugs.”

Although this summer’s protests were sparked by Floyd’s death, Cooley says, they are part of a centuries-long fight for Black freedom in America.

“This oppression is not really new,” she said. “This has been our reality from 400 years ago. It has just taken different shapes.”

“Long time coming, our country has been on simmer. Here comes the vigorous boil as reality becomes grimmer.”

Cooley’s participation in recent protests has inspired her to make advocacy and political change central to her future career.

“I looked around me and just realized this is something I am so passionate about. This is something I would like to go into in my life,” Cooley said. “I looked at my brother and I said, ‘I think I might want to be a senator or a policy reformer or someone in office with the power to create the changes I want to see in the world.”

“You use one hashtag and a black screen and think we should be proud of you, avoiding the countless Black bodies that come before and then still defending the blue.”

In Providence, Cooley marched with friends from her high school to the steps of the State House. While military, National Guard, and police forces lined the streets with guns, body armor, and tanks, the protesters refused to be daunted.

“Once we got to the State House, the police were starting to gather in. They were all lined up with guns and riot gear and we started a chant, saying ‘I don’t see no riot here, why are you in riot gear,’” Cooley said.

Although other protesters urged her to leave the State House where police were organizing and return to marching in the streets, Cooley remained. “I didn’t want to go back to the streets. I wanted to stay on the steps of the State House fighting for what I believe is just.”

As 9 p.m. drew nearer, the crowd convinced the police to delay the curfew by eight minutes and 46 seconds, the exact amount of time Minneapolis Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck.

As her family began to worry about the approaching curfew and called her cell phone, Cooley walked alone past lines of officers down a Providence street usually packed with cars and shoppers. “I walked past with all the people strapped up and ready for anything with those big guns,” she said. “I felt so powerful in that space.”

“Some say we talk too much and add too much noise, but, bitch, I am here, I am Black, and I handle it with poise. Black Lives Matter. Today, everyday, and forever.”

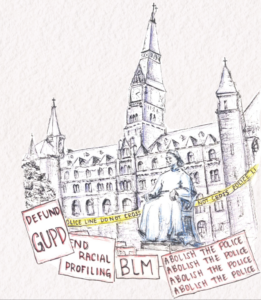

[…] Social Justice and focused on systemic racism, police brutality, and voting rights in the midst of nationwide protests following the police killing of George […]

This is a fantastic piece of reporting, and a story that needs to be told from many angles, as Roman so remarkably has done. Clearly, he understands that the most powerful way to tell a story is to let those involved speak for themselves. The journalist listens. And now, readers of The Georgetown Voice are listening. Thank you.