At first glance, the seven-inch tall Webkinz known as Chunky the Panda is unassuming and sweet. After the pandemic scattered Georgetown students across the globe, its “guardians” shipped the stuffed bear to selected Hoyas, documenting each visit on its Instagram account. It quickly gained popularity, amassing nearly 2,600 followers and garnering the attention of the Smithsonian Zoo and the McDonough School of Business. Its high visibility has shaped Chunky into an unofficial school mascot, a status it has sought to formalize in recent GUSA elections.

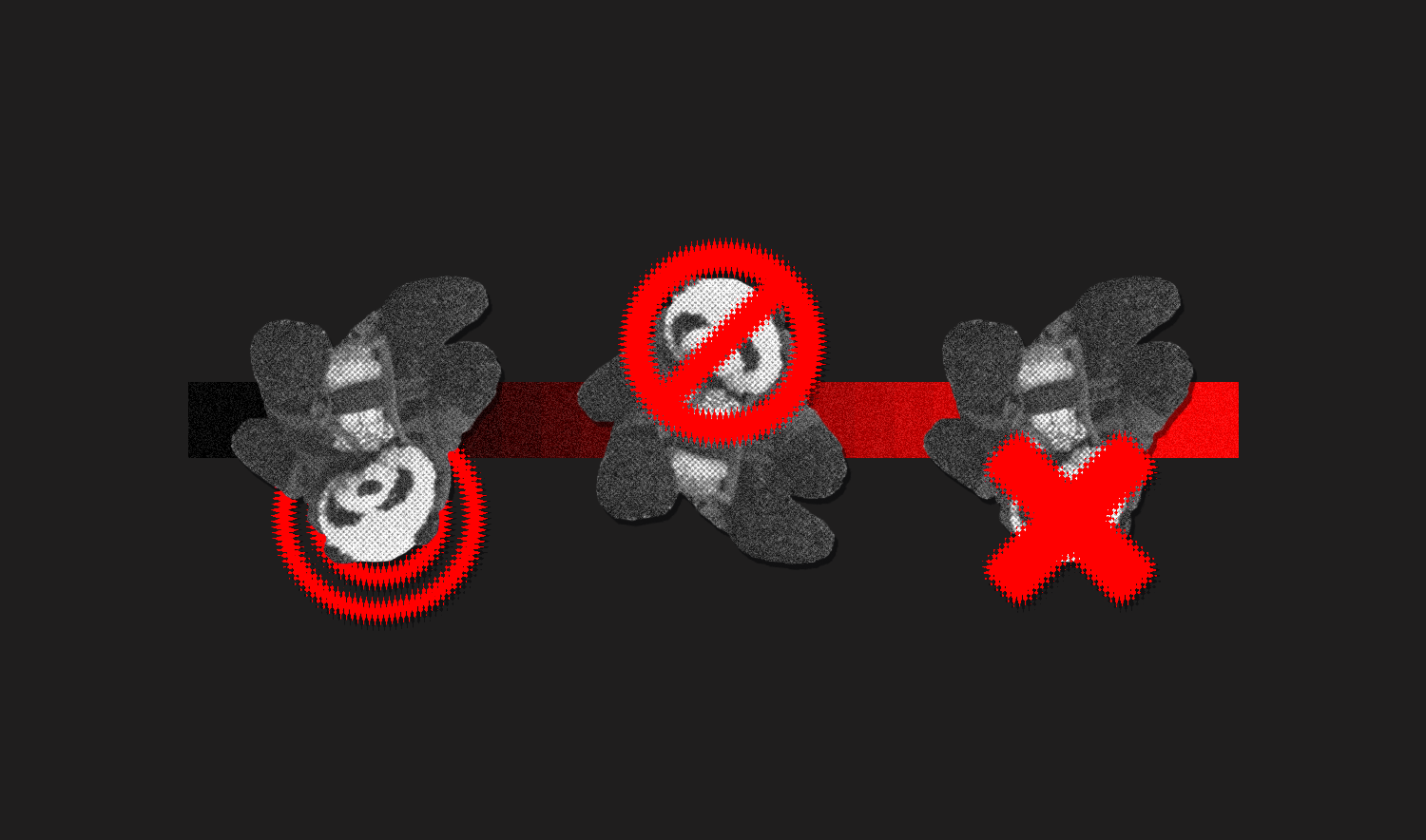

In an age where a social media platform amplifies ideas, Chunky’s outsized influence makes what it represents all the more important. Cloaked under a cotton-soft appearance, the bear is a manifestation of willful ignorance, exclusion, and competitiveness. De-platforming Chunky through unfollowing it is a much-needed rejection of the racial insensitivity, ableism, and toxic club culture that it represents. If we want to imagine Georgetown as a more thoughtful, inclusive campus, we deserve symbols that say as much.

On matters of race, Chunky earns a failing scorecard. In Chunky’s first post on Instagram, the bear sits in the lap of the statue of John Carroll (a time-honored tradition that is problematic in its own right), who is wearing a pink durag, a cloth cap popular in Black communities that protects and stylizes traditionally Black hair. The durag was draped on Carroll during the Black Survivors Coalition (BSC)’s five-day-long occupation of Healy Hall, where they demanded better resources for survivors of sexual assault—especially those who identify as Black, femme, and/or non-binary. As part of one of the largest student protests of the year, the BSC campaign plastered posters outlining a set of critical resource needs just thirty feet away from the statue.

The Chunky account, however, chose to be explicitly ignorant of the ongoing needs of Black students on campus. The photo of durag-wearing John Carroll is captioned, “Hello Georgetown, Can’t find a better way to start this morning than meditating with my friend Johnny (although I don’t know why he’s wearing a pink headband today) 🐼🙏🏻🎋.” It’s an insensitive dismissal of not only the highly visible activism done by a diverse coalition of students at Georgetown but also of Black culture. Reducing a durag to a “pink headband”—and decontextualizing its purpose—is at best ignorant and at worst malicious, and either way poor behavior to idealize.

Perspective limitations have contributed to other misfires, too. A mid-August 2020 incident generated backlash in the Class of 2024 GroupMe, where a Chunky representative attempted to compare the word “stuffed” to a slur. Chunky’s totally arbitrary attempt to frame an innocuous word as a slur trivialized the real harm that actual racist slurs have on people of color, and spoke again to the disconnect between the Chunky symbol and students of color on campus.

From a representation standpoint, Chunky presents a vision of Georgetown that is dominated by white students. Of the students featured on the Instagram account, only around 18 percent of them are non-white, compared to between 33 and 52 percent of the student body. It is well-known that Georgetown is a predominantly white institution, and we, the Voice, are not exempt from that. Our editorial staff skews heavily white, and it would be hypocritical to frame many of the other institutions (including ours) as accurately representative of all identities at Georgetown. Simply put, centering, platforming, and empowering students of color is critical work that almost all spaces at Georgetown still have to do.

Still, Chunky’s representation of Georgetown matters. As a potential mascot, current and future students may associate Chunky with the “face” of the university, which dictates who most belongs. Who gets featured on Chunky’s page is a deliberate, planned choice. And to boil Georgetown’s essence down to an image that is so unflinchingly white excludes and minimizes the students of color that make—and will make—Georgetown the extraordinary campus it is.

Apart from a lack of fair racial representation, Chunky’s account presents a blasé attitude around economic access, perpetuating a mentality not uncommon in the 21 percent of Georgetown students that hail from America’s top 1 percent. Chunky’s casual Instagram stories depicting first-class flight tickets and giving its audience the power to choose which $1,000+ winter jacket it should buy reinforces a social norm that material wealth is assumed for students. When even basic housing security is under threat for so many, Chunky’s choices feel out-of-touch.

From a disability advocacy standpoint, Chunky the Panda has also failed to ensure representative integrity. From early on, Chunky has positioned itself as an “advocate” for nonverbal autistic people. Yet Chunky’s early advocacy for Autism Speaks—an organization well known in the autistic and disabled community to be harmful, paternalistic, and stigmatizing—points to a deep disconnect with many nonverbal autism advocates.

Chunky’s “guardians” have gone as far as saying the bear itself is nonverbal. But representing the nonverbal autistic identity as a stuffed animal presents its own set of challenging optics. Simply put, nonverbal autistic people—and disabled people in general—are not cute toys to be photographed with or items to be controlled. Imagining the condition as such is dangerous and paternalistic. Moreover, autism spectrum disorder is a real medical condition—and assigning this identity to a stuffed animal that simply cannot speak as a result of being an inanimate object potentially minimizes this reality.

Not only that, but Chunky has failed to center the actual experiences of nonverbal autistic people. The account touts normalizing the experience of having nonverbal autism as a central mission, but it rarely seems to bring up this identity outside of interviews, nor does it feature real people with nonverbal autism, who are fully capable of advocating for themselves. As a result, the nuanced experience of being nonverbal is not depicted at all.

For an advocate, Chunky’s account also contains little to no political engagement on important policies, besides running polls about whether America is the greatest country on Earth and SCOTUS expansion. It throws no weight behind disability-competent health care, Medicaid expansion, accessible infrastructure, or countless other policies that disabled advocates have identified as important. In doing so, Chunky dangerously obscures real political needs, diluting the urgency of nonverbal autism advocacy into a feel-good cause.

Outside of “visiting” Hoyas, Chunky dedicates time to orienting new Hoyas to the Hilltop, posting regular content about joining clubs and pursuing internships. Yet even on what should be a relatively benign subject, Chunky perpetuates harmful ideas about what success constitutes. Nearly all of the clubs Chunky posts about are application-based organizations—GUSIF, GUAFSCU, HMFI, Hilltop & Innovo Consulting, Blue and Gray, Georgetown Ventures, etc.—several of which boast notorious single-digit acceptance rates amongst hundreds of applicants.

Like that at many elite universities, Georgetown’s club culture prides itself on exclusivity (often at the expense of students with marginalized identities) despite being a central social driver. The result is a large percentage of the student body predicating personal worth on whether a bunch of strangers think you’re “the right vibe” or not. Needless to say, it’s unhealthy, disempowering, and totally unnecessary—Chunky could easily feature a diverse set of interest-based open membership organizations but deliberately chooses not to.

From a career perspective, Chunky presents an incredibly narrow view of the future. Instead of encouraging Georgetown students to pursue diverse, worldly passions, Chunky intensifies the stress culture narrative that a future career looks like a binary between finance and consulting situated at Goldman Sachs or McKinsey firms in D.C. and New York City. That’s not to say these options are wrong—many Georgetown students end up pursuing them—but for a potential mascot of the university to frame career options in such an exclusive light is disappointing.

In many ways, Chunky only perpetuates an image of success that is intensely pressurized and myopic, pushing so many students to either ruthlessly work towards careers they may not enjoy or feel as though they are out of place. As a Business and Global Affairs major—which Chunky strangely claims to be himself, though none of his “guardians” are in my cohort—I come to class every day faced with this one-note narrative, and I cannot help but wonder how framing this stuffed animal as a representative Hoya will add to this stereotype.

If I haven’t made enough of an argument for why everyone should unfollow Chunky, consider the alternative: a mascot that genuinely promotes a vision of the university that is empowering, representative, and thoughtful. While Chunky is the superficial crux of this article, what I am truly hoping for is a campus that is more deliberate about who and what it chooses to platform. A campus that seeks to place the voices and personhood of those they advocate for in center light. That fights for systems to make our world genuinely better. That idealizes Hoyas who care for their whole person and their whole community, not one that squeezes them into narrow pictures that so many cannot see themselves in.

We can do so much better than Chunky. Unfollow it, and maybe we will.