Dear SFS Undergraduates:

You are among the most talented college students in the country, if not the world. As with undergraduates at any institution of higher learning, you deserve a faculty and curriculum that honors and cultivates your unique abilities.

After 17 years of teaching in the School of Foreign Service and writing about college pedagogy, I am of the opinion that the SFS is failing you. This administration and faculty, I believe, need to radically rethink their commitments to undergraduate education.

I have framed this analysis in terms of basic rights that you possess. I hope these comments–they’re really lengthy, sorry about that–let you start your own conversations and frame your demands of the SFS administration.

1. You have a right to be taught by SFS tenure-line professors. In an elite academic unit, such as the SFS, you should have plenty of classroom engagement with tenure-line professors. We are the ones who, in theory, publish the most peer-reviewed research (i.e., the currency of scholarly achievement).

The expectation is that those of us on the tenure-line will deliver our specialized knowledge to you in the lecture hall. Yet that expectation is not being fulfilled in the SFS. Accurate data is hard to come by (see below), but my rough estimate indicates that only a quarter of the SFS courses you take are taught by tenure-line professors.

Now it is true most tenure-line professors at R1 universities like ours prefer to teach graduate students, or not to teach at all. But in the SFS, that preference has reached a whole different level. There is, I will argue, an almost structurally-mandated disconnect between us and you, between what we are incentivized and built to do and what you need as students.

Most of your class contact hours in the SFS are spent in the company of non-tenure-line professors who work full time (abbreviated as FTNTL), and adjuncts who are hired on a semester-by-semester basis. At a meeting last June, it was revealed that the SFS, across all of its divisions, employed 352 adjuncts—more than any other Georgetown school, even ones that are much larger than us (like the College).

The FTNTLs and adjuncts, I stress, are often accomplished scholars in their own right. They too publish peer-reviewed research, some publish more than our tenured professors! They are not the problem, but part of the solution. Rather, the manner in which they are underpaid—that is the problem.

The financial hardships they endure, and the professional courtesies denied to them, cannot be left out of any structural analysis of the SFS, and American higher education in general. Let me give you a sense of the discrepancies. According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, in 2018 tenured Full Professors at Georgetown earned an average salary of $208,000, tenured Associate Professors $133,000 (it varies, but Fulls and Associates usually teach 4 classes a year, at least half of which, I surmise, are on the graduate-level). FTNTLs work on usually limited contracts, earning between $60,000-80,000 a year (they usually teach 5-6 classes per year). Adjuncts are paid $7,500 per class.

So with an acute awareness of how immoral this system is, I’ll mention a few reasons why you have a pragmatic interest in being taught far more frequently by those of us on the tenure-line. Because tenure-line professors are supposed to be leaders in their academic fields. Because, once tenured, we have lifetime appointments and full academic freedom protections (we can thus take intellectual risks in our classes without fear of reprisal). Because tenure-line professors are amply compensated to serve as mentors during your years on the Hilltop. Because our lifetime employment means that we can shape long-term goals, like the BSFS curriculum.

2. You have a right to a coherent curriculum. The BSFS curriculum is, to put it mildly, a baffler. Generation after generation complains about its rigidity. SFS undergrads often have little idea why it demands what it demands and does what it does. The preponderance of mandatory economics classes, the Eurocentric framing of history courses and “Map of the Modern World,” are common student concerns.

Every now and then, the curriculum suddenly draws down, or lurches towards some new and unanticipated horizon. An example of a puzzling lurch is the B.S. in Business and Global Affairs program, which seemingly arose overnight. It was endlessly hyped by the SFS Dean’s Office, which advertised it specifically to prospective students and herded undergraduates into the shiny new initiative.

What happened next was disconcerting, but predictable: the SFS Faculty–who, in fairness, were never really made a partner to the scheme–decided they just weren’t that into it. As best, I can tell, this major, which now houses more than 100 students, has only one SFS tenure-line professor (heroically) contributing to its development.

One also wonders why so many crucial areas of interest to students of international affairs are so poorly represented in the SFS curriculum. I may be crazy, but I happen to think that India and China are subjects of vital importance in a school of global studies. But I don’t see any systematic progression of courses that could meaningfully connect the expertise of our faculty with the needs of undergraduates studying these areas. I notice the same shortcomings when it comes to religion and global affairs within the SFS. Ditto for subjects related to the arts, like cultural diplomacy or “soft power.”

I’m not denying that you’ll find some stray SFS classes on any of these issues. But what you are missing out on is a coherent curriculum. A curriculum is a sequence of courses carefully designed (and constantly updated) by experts in the field intended to develop and deepen your understanding of a complex issue. A curriculum grows with new developments (e.g., the rise of Tech or conversations about critical race theory). A curriculum is like the intellectual house in which students live, one built and constantly renovated by faculty experts.

The SFS curriculum, however, is scattershot, with some reasonably coherent majors and others moored in the Bush era (H.W.). Why? Few tenure-line professors are invested in this project. I cannot remember even one faculty-wide discussion about what we expect a BSFS student to learn during their time on the Hilltop, the type of mind we are trying to forge, a collection of baseline knowledge, etc.

Instead, decisions about the curriculum are usually made by the Dean’s Office in accordance with a rigid, secretive, top-down model that has overtaken the university in the past decade. Thus, a few hand-selected professors are invited to shape curricular matters. Their proposals are then fast-tracked through apathetic, rubber-stamping committees, then back up to the Faculty Council (composed only of tenure-line professors and hence many people who rarely or never deal with undergrads), and then imposed upon you.

If a curriculum is a house, then the SFS is a brokedown palace of disjointed courses.

3. You have a right to curricular initiatives built by experts. There has to be a fit between a curriculum and those entrusted to create it. Many crucial areas of inquiry in the SFS undergrad curriculum are overseen by scholars who are not experts in those fields.

I have signed countless petitions from justifiably irate students about the state of India and South Asian studies at the SFS. The irony is that we do have a few top-flight scholars of India on our faculty, often left out of the curriculum decision-making processes. Shouldn’t they be the ones tasked by the SFS to build a coherent program of study geared to this area? And shouldn’t they work as a collective?

The graduate/undergraduate distinction is relevant here. Tenured scholars, as I noted, would usually rather work with graduate students. Usually, a responsible administration forces them to not overlook undergraduates. That cat-and-mouse game simply does not occur in the SFS. The FTNTLs and adjuncts make up the deficit.

As a result, there are fewer experts to engage in the truly arduous task of undergraduate curricular reform and creation (and teaching). Often we’re lucky to find FTNTLs or adjuncts to plug the holes. But given how little they are paid, how lucky can we get?

4. You have a right to mentorship. In the “pre-professional” environment of the SFS, mentorship is crucial and expected by incoming students. Many of us have vocational connections that could be vastly helpful in your professional development, not to mention advice.

Each and every one of you deserves at least one Faculty Mentor. These mentors could be tenure-line, FTNTLs, or adjuncts. It is the job of the administration to incentivize (and then force) scholars at all ranks to work with you, especially the non-tenured professors who graciously mentor, yet are never compensated for their efforts.

5. You have a right to accurate data about matters that directly impact your education. For an allegedly data-driven school which employs battalions of quantitative social scientists, it is amazing how little factual data about the SFS can be retrieved.

Here are some basic questions you need to ask of your school: What percentage of your SFS classes are taught by tenure-line professors, FTNTLs, or adjuncts? What do course evaluations reveal about the quality of the educational product we deliver? How is that data used, chopped, and applied? What percentage of SFS resources are devoted to funding graduate versus undergraduate education?

Then there is broader institutional data. From 2015-2020 the SFS ran a massive fundraising drive. The campaign was supposed to raise something like 250 to 350 million dollars. If memory serves, 50 million dollars alone was earmarked for capital improvements to the aging ICC building. These renovations would be prudent; the main doors to the building have not really worked properly for fifteen years and students crowd into airless, shoebox classrooms. Also, we freeze in our offices.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that every aspect of our existence in those five years was keyed to the “Centennial Campaign.” The curriculum was tweaked to emphasize “Centennial” themes. We were subjected to PowerPoints about “Centennial Pillars,” “Centennial Scholars,” etc. The infamous, astronomically expensive, and completely unregulated, “C-Labs” kicked into overdrive. Celebrated as a pedagogical innovation, the Labs hurled students across the globe (with the scantest of faculty oversight, I might add) and into situations which some of them later dubbed “colonialist poverty porn.”

For half a decade, the entire SFS went into what can only be described as party-planning mode. We held fund-raisers across the globe. We staged a massive “gala” in DC. Yo-Yo Ma performed. Bill Clinton addressed the crowd. People dressed up.

And then: silence. Did we raise the 300-350 million dollars? Did we raise even half of that and what was it used for? Who knows? No one ever told us. All I know is that the doors to the ICC still don’t really work. Faculty still wear coats in their offices.

6. You have a right to know what types of relations the SFS has with outside organizations and donors. The fate of the Centennial Campaign is mysterious. Actually, the SFS is full of mysteries, many involving major donors. The latter are increasingly “calling the shots,” not just at Georgetown but at universities across the country. Welcome to the neoliberal university, my friends!

Some donors are wonderful, generous souls. Others are motivated by less than purely altruistic concerns. You’d be surprised to learn how many of our initiatives and programs reflect donor interests. It’s your right to know how these philanthropic endeavors impact your classes, curriculum, and the slate of speakers we invite to campus.

Then there are relations with other actors. I, for one, was very surprised to learn of the various robust relationships we have with the World Bank. I always thought that as a leading school of international relations it was our remit to study the World Bank, not to become its partner and essentially its outpost in Northwest D.C.

The SFS engages with all sorts of DC organizations, be they NGOs, three-letter government agencies, or philanthropic foundations that influence our principles and curriculum. You need to know more about these connections.

7. You have a right to an optimal ProSeminar (and Senior Capstone) experience. Did you like your ProSem? I think I can answer that! It depended on your instructor. Some of you had excellent teachers (regardless of rank). They conveyed the fruits of their research to you in the hot-house atmosphere of your first SFS class. As for the rest of you, the less said the better.

Why is the ProSem experience, which all first year SFS students take in their first semester, so uneven? We usually offer 20 to 25 freshmen Proseminar sections a year. In my experience we’ve never been able to staff half of those courses with tenure-line professors (sorry kids, even though there are about 80 of us, we have better things to do).

Instead, we farm out the duties to FTNTLs and adjuncts. Some of them do a great job. Still, crucial opportunities for future mentorship are diminished.

More importantly, we’ve never reflected together as a faculty as to what the learning outcomes in ProSems should be, what pedagogical approaches should be employed, what are reasonable work loads for students, etc.

8. You have a right to DEI initiatives that serve you. Plainly speaking, the SFS faculty has long had a diversity problem. When I arrived here in 2005, I was stunned by how few women and scholars of color were on the SFS tenure-line faculty. It was only two years ago, in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, that the school started to address issues of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. This has resulted in a number of tenure-line diversity searches and hires.

This is a step forward, but if those scholars are mostly going to teach graduate students and receive “release time” to do research–and in fairness to them, that is what they should expect insofar as this is the SFS norm–then how does that help undergraduates? To expect this diverse cadre of professors to cater to your intellectual, curricular and mentoring needs is unfair to them because we don’t expect that of our other tenure-line scholars.

In truth, the SFS missed a step, as it often does. Prior to establishing a DEI initiative we should have had something on the order of a “Truth and Reconciliation Committee.” The committee would have investigated how it came to pass that our faculty in 2020 had less diversity than a Southern Baptist Theological seminary might have had (in 1990). This exercise would reveal that the SFS has a culture of exceedingly poor decision-making.

We have an obligation to learn from those mistakes. In the future we need to make decisions around crucial DEI issues that draw upon the expertise of the faculty. We need to make all of our scholars and you, stakeholders in this process.

9. You have a right not to be a photo op. Our SFS Twitter feed often features images of you, reflecting, learnin’, basking in the glow of some ambassador or billionaire Tech Bro (SFS ’17) who dropped by your class on his way to a Nats game. You’re free to do what you want with your public image. My advice is don’t provide these optics until the SFS takes your education seriously.

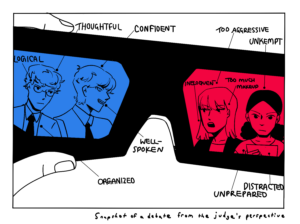

10.You have a right to a faculty governance structure that serves you. Here’s a story that sort of sums things up. A few years back we conducted a search for a tenure-line faculty member. When the on-campus interviews for our finalists were being arranged, I scheduled a “teaching demo,” which would offer students and faculty an opportunity to see the candidates teach in a classroom setting.

This is routine at nearly every college in America. It offers an important, albeit imperfect, glance at a professor’s potential as a teacher. It also gives the students a stake in the process.

A few days later I was informed by our Faculty Chair that such teaching demos were in violation of our SFS statutes. I asked to see that statute, only to learn that no such thing officially existed. I was then told that a senior member of the SFS remembered that such a statute used to exist–back in 2004, he thought–and had become a “norm.”

Many colleagues later told me they supported this ban on teaching demos. They were worried that such exhibitions would discourage highly-qualified scholars from coming to the SFS (i.e., we might be construed as the type of sketchy place that demanded undergraduate teaching). They thus supported the principle that we should know nothing about the teaching abilities of people who were eligible for lifetime appointments in the SFS.

Do you think this might have some correlation with the quality of the pedagogical product we deliver?

***

Why is this happening? The reasons for our woes are many and complex–and not unrelated to broader, disturbing national trends in higher education.

Still, it is obvious to me that our leadership is underperforming.

Too, I would add that we are beholden to a dysfunctional faculty governance structure. We abide by a constitution that makes it virtually impossible to effect any sort of meaningful change. It silences dissent. It facilitates the marginalization, even bullying, of faculty with differing views. It rewards tribalism and coalition-building (often referred to as “collegiality” in SFS Speak). Moreover, our governing documents seem completely oblivious to our responsibility to undergraduates.

The tenure-line faculty also deserve a share of the blame. Professors in the SFS like to refer to the school (privately) as a “failed state.” As often happens in such a place, people form protective networks to guard their interests. These growing professorial tribes defend their turf, negotiate with one another when expedient, and protect their own.

Aside from the nihilism of it all, this is unpleasant for those who have no desire to belong to a tribe. It’s downright scary for junior faculty on the tenure-track who must quickly learn to pick a side (or two sides that are presently not at war) and lay low. And it is absolutely lethal for the prioritization of undergraduate education.

What can be done? It’s up to you to pressure the SFS administration to address these problems. My advice is that no matter what the Dean’s Office tells you, adhere to the motto “Don’t believe, verify!” In my experience, accurate data about the SFS is not freely dispensed. Moreover, be wary of explanations based on “personalities.” The SFS’s woes are structural and cultural, not personal.

If I were you, I’d demand a few immediate course corrections. Whether these will alleviate the problems discussed above is an open question. But as Antonio Gramsci once said, “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.”

Demand fair pay and proper working conditions for the adjuncts and FTNTLs who are presently your primary point of contact with SFS professors.

Demand that all new curricular initiatives be staffed, overseen, and developed by a collective of experts, not apparatchiks, and that you are privy to the process.

Demand that every BSFS student receive a designated Faculty Mentor.

Demand that all ProSems be taught by tenure-line SFS professors with a track record of scholarly publication and a solid teaching record.

Demand that DEI hiring initiatives directly serve undergraduates.

Demand a required, 3-credit course on “Global Racism/s” (to replace the 1-credit “Map of the Modern World” perhaps?) built collectively and transparently by experts on this faculty and taught by the appropriately credentialed scholars

Demand to know how resources are proportionally allocated to graduate versus undergraduate students.

Demand the right to basic data about SFS relationships with outside agencies and actors.

Demand that the tenure-line SFS faculty and FTNTLs form a committee to engage in monthly discussions about our curriculum, teaching, and undergraduate issues.

Demand that the composition and leadership of the aforementioned committee not be left to the Dean’s Office and the Faculty Chair.

Demand that many of you sit on this committee.

The good news is that there are committed teacher-scholars on this faculty at all ranks. We are ready to work with you and provide you with the education you deserve.

Yours in solidarity,

Jacques Berlinerblau

Jacques Berlinerblau is a Professor of Jewish Civilization in the Walsh School of Foreign Service. From 2005-2020 he directed the Program for Jewish Civilization which in 2016 became the Center for Jewish Civilization. From 2015-2018 he served on The University Committee on Rank and Tenure, becoming its chair in his final year. In the past year he has published three scholarly books on the subjects of global secularisms, Philip Roth, and African-American/Jewish-American relations (the latter co-authored with Professor Terrence Johnson). The work most relevant to the analysis above is his Campus Confidential: How College Works, Or Doesn’t, For Parents, Professors and Students and numerous essays in The Chronicle of Higher Education. His current research project is on comedy and international affairs. He invites commenters and critics to write to him at jdb75@georgetown.edu. His twitter is @Berlinerblau. His personal website is jberlinerblau.com

This does not only apply to the undergraduate program but the master’s program as well.

Professor Berlinerblau, THANK YOU for speaking up and shedding light on the obvious issues with our undergrad education. I agree with 99% of what you have written. It seems like the tenured-line profs are trotted out primarily to showcase for alumni webinars, but they rarely/never teach undergrads, e.g. Medeiros, McNamara, Arend, etc. I’d like to add one more issue with the preponderous number of classes taught by FTNTLs – the great majority of their classes are taught at night. And since we often take 3 classes with FTNTLs, we are essentially “Night Students.” We didn’t come to Georgetown to be Night Students!