If you registered for classes this week, you might have selected the English Department’s “Witches, Bitches, Bimbos” or the Anthropology Department’s “Cupcakes/Pies/Power.” You could be planning to study one of Georgetown’s 20 languages, from Korean to Farsi, or the current geopolitical crises in Ukraine.

In 2022, however, you cannot study classic Georgetown courses like “Steamship Classification & Construction” or “Ports & Terminals.” Nowhere on MyAccess will you find “Wharf Management,” “Marine Insurance,” or “Physical Training and Hygiene.” Over the decades, Georgetown’s academic focuses have adapted alongside new demands (and a decreased interest in the ins and outs of naval stewardship). Today, student efforts around academics have shifted to establishing more diverse curricula, deepening regional studies, rethinking diversity requirements, and hiring faculty of color. That progress, however, hinges on donor interest and the machinations of curriculum building.

Georgetown’s curricular focuses have always correlated with geopolitics. “There’s no doubt, course offerings are highly responsive for what is going on in the world,” Anthony Arend (SFS ’80, MSFS ’82, PhD ’85), Government professor and former MSFS director, said. During World War I, Georgetown’s curriculum shifted from traditional liberal arts towards an emphasis on international business and language. “There was a sense in which the world had undergone fundamental change,” Arend said.

World War II and the Cold War sparked academic regional focuses in Russia and Eastern Europe; after 9/11, class offerings analyzing terrorism grew like never before. Interest in climate change and global health led to the 1982 addition of the Science, Technology, and International Affairs major. Asian and African Studies also joined the academy in the 1980s, following increased awareness of postcolonial impacts.

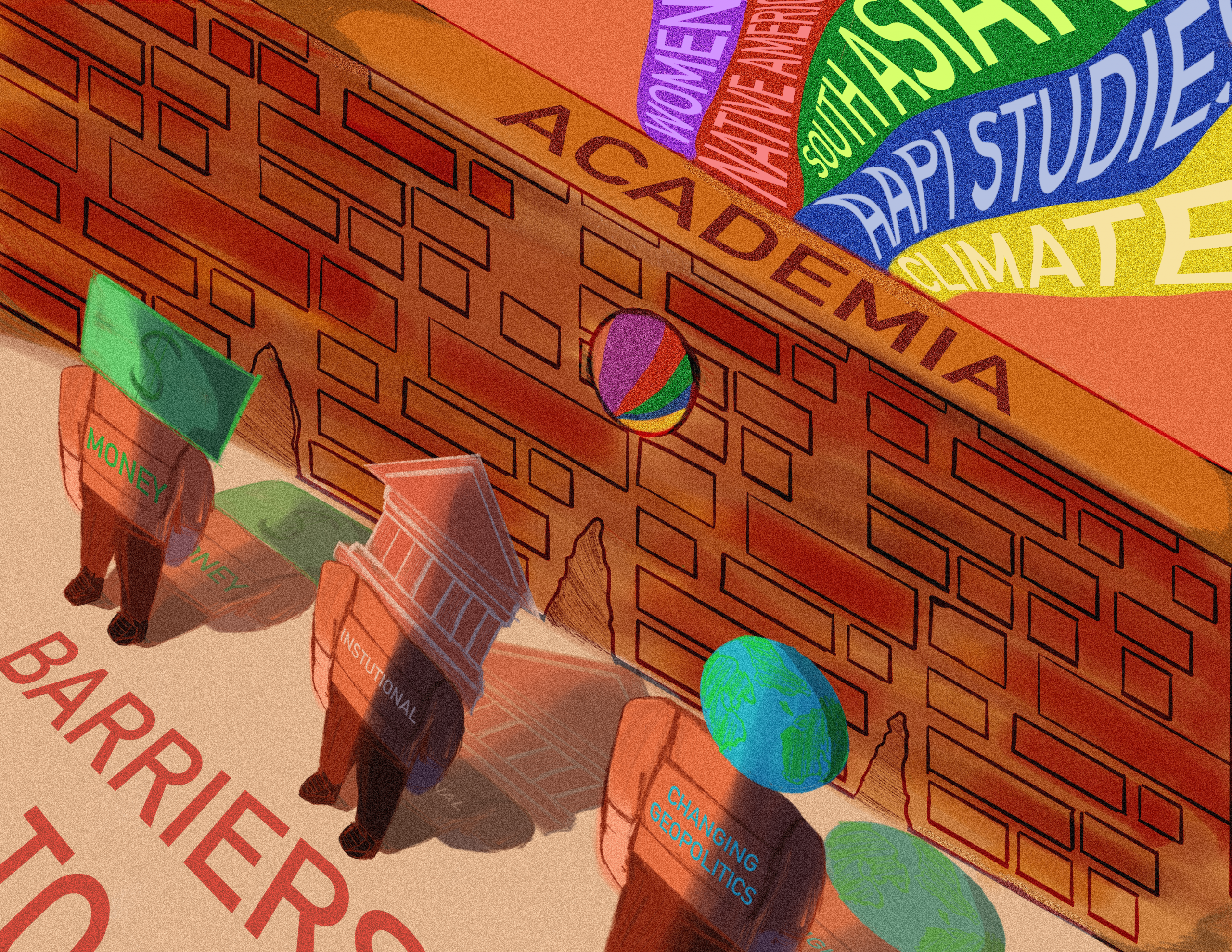

But students don’t think this evolution is complete. Lucy Doyle (COL ’22), co-president of the College Academic Council (CAC), hopes to see new programs built around student requests for regional and ethnic studies, referencing petitions for South Asian, African, Indigenous, and Asian American and Pacific Islander studies. “I would like to see more institutional support given to the programs that are popular amongst students and culturally relevant but hindered by funding and staffing issues,” Doyle offered.

CAC isn’t the only academic group that wants change. Felipe Lobo Koerich (SFS ’21, LAS ’22), former president of the SFS Academic Council (SFSAC), identified large worldview gaps within the SFS curriculum. “We still focus far too much on the United States when exploring IR [International Relations] and diplomacy,” he argued. “Most of what we learn is from the U.S. perspective almost exclusively and then tends to focus on Europe or to a lesser extent China/East Asia and the Middle East. Africa is glaringly ignored unless you go out of your way to study it.”

Georgetown’s curriculum has long been rooted in a western bias. When the SFS was founded in 1919, its initial purpose was to produce businessmen and merchants in collaboration with the Department of Commerce, not State, as the U.S. began to emerge from isolationism. Foreign policy only extended to America’s economic interests in Latin America and Western Europe. A 1924 comparative politics class only covered European states and commonwealth governments, only going as eastward as Turkey in the syllabus.

According to Arend, Georgetown’s strategic plans for its curriculum are determined by faculty and deans in each school, in conversation with student representatives from elected academic councils. But Georgetown’s curriculum does not respond to student requests without another powerful variable: donors.

Students pursue majors within institutionalized departments, like Government, while programs, like Asian or African Studies, are a collection of courses students can sample at their pleasure or achieve minors and certificates in. New programs are created when there is adequate funding to hire an endowed chair who can develop the curriculum and recruit faculty. According to Arend, this funding comes mostly from donors. He pointed to the Prisons and Justice Initiative directed by Marc Howard and the Center for Security and Emerging Technology. “How do we get to do more? We connect with donors who can support various aspects of that program,” he said.

Lobo Koerich confirmed that donations are critical for curricular development. “Funding and staffing consistently came up as barriers, often closely intertwined as the university expressed concerns that it did not have the faculty with the expertise,” he said of his time as SFSAC president.

While donors influence the development or creation of new programs and departments, Arend argued new curricula must also line up with a school’s goals. “The academic goals of the university are driving what we want to do with the fundraising, it’s not that the fundraising is driving the academic goals,” he said.

Still, bureaucracy and lethargy associated with curriculum evolution cause further snags, according to Lobo Koerich.

As it stands, professors are often stretched thin between semi-developed programs. Programs offer academic flexibility to students because professors from multiple disciplines can teach courses, but they also lack the funding and faculty of departments. “Professors whose academic home is in a program need to have a dual focus, in a program and a department,” Doyle explained, describing split priorities.

With professors’ attention divided, a program’s offerings change with adjunct lecturers and further curriculum waits on donors to fund chairships. “These bureaucratic obstacles limit professors and ultimately affect students,” Doyle added.

Donors are critical to the growth of programs like Asian Studies by paving the way for additional faculty. Alongside Michael Green and Evan Medeiros’ appointments to director and Penner Family chair positions respectively, 16 adjuncts fill in the non-endowed teaching positions. Most are professors of color and take on the bulk of the instructional load, despite being paid less than tenured or assistant professors. With limited resources, the program covers Asia broadly, with little specification into South or Central Asia, or Pacific Islander and Asian American identities.

Georgetown’s African Studies program is directed by Lahra Smith, but the study does not have its own department. The program is supported by 14 faculty, only three of whom are officially titled as African Studies professors. African Studies relies on 10 adjuncts as well as faculty from other fields.

Arend explained that Georgetown has had Asian and African studies since he was an undergraduate, pointing to a track record of expanding curriculum, even if there is opportunity to improve. “We need to do more in Asia, we’ve seen strengthening of those programs,” he said. “I’ve seen a trajectory which is dramatically increasing in that area, the same with African Studies.”

Doyle believes the university should be more transparent about its academic plans. She acknowledged hiring new faculty is not a quick process. “But they could be more communicative of what subject matters they are hiring for so students had a better idea of their future priorities,” she added.

But creating new programs for specific regions is just one step in improving the diversity of curriculum. Lobo Koerich and current SFSAC president Satya Adabala (SFS ’22) argue that a comprehensive, anti-racist review of existing courses is essential for future curricular growth.

In the past, SFSAC proposed expediting the hire of diverse professors to instruct both regional and entry-level courses, like “International Relations” (IR) and “Comparative Political Systems” (CPS). The goal was to diversify the identities and perspectives of the professors who guide each class with examples from their areas of expertise and lived experiences. “Having professors from diverse regions that specialize in regions outside of just U.S. foreign policy, Europe, or China/East Asia could introduce the same effect,” Lobo Koerich explained. “Imagine learning CPS from an Africanist that uses the region for examples and literature.”

According to Adabala, the SFSAC is actively working with the administration on proposals to center core SFS classes around authors of color, women, and academics from non-western regions. “The idea is to get more voices into the syllabus,” she said. “It shouldn’t just be that we study white male authors then tack on five authors of color at the end, but rather that you are engaging meaning with different sources and perspectives throughout,” she said.

SFSAC has a proposal to restructure required introductory courses like “Political and Social Thought” (PST), IR, CPS, and SFS history offerings to contextualize theories around race and society and recognize the racism of many historic thinkers. Adabala explained that philosophy courses could still include readings from syllabus mainstays like Locke and Rousseau, but should also discuss how their philosophies were published within a European-centric, white society and conditioned how elite Europeans viewed—and treated—non-white people.

“How much do their philosophies only apply to certain people? And are they applying to the wider groups of people that existed in society?” she asked. “What were their attitudes and opinions towards race and towards women?”

“Maybe there is a new way of teaching PST,” Adabala said.

The SFSAC’s work is reflective of a much bigger effort to diversify the core curriculum: an entirely revamped diversity requirement. Before graduation, all undergraduates must fulfill two “engaging diversity” courses: one international, one domestic. Adabala said while she’s glad the current diversity requirement exists, its current review provides an opportunity to invite students to reflect on diversity and race in a more meaningful way.

In the summer of 2020, Amanda Yen (COL ’23) and Natalia Lopez (SFS ’22) surveyed student interest in changing the diversity requirement. They were recruited to research with the Hub for Equity and Innovation, which led a 2021 project to get a better understanding of the state of the diversity requirement.

According to Adabala, findings showed that the current requirement applies to dozens of courses with vague relevance to meaningful discussions on race and racism. The research identified one student, who after taking 40 courses, found that more than 30 of them filled the diversity requirement. “The language is too vague,” Yen wrote in an email to the Voice. “It seems to be centered more on recognizing diversity of experiences than on structures of power; in fact, the word ‘diversity’ is open to really broad interpretation.”

“It requires more thinking about which courses are being flagged as ‘diversity,’” Adabala said of the current requirement. “How effective is it? Is it fulfilling the purpose of what it is trying to do?”

After the report, Rohan Williamson, vice president of education, asked Yen to co-chair the Diversity Requirement Committee. Alongside Alisa Colon (COL ’23), Yen offers student input into the design of a new diversity requirement, which is proposed to the Main Campus Core Curriculum Committee with upper-level administration.

“I believe an updated and expanded requirement should include discussion about systems of power, privilege, and oppression,” Yen suggested. Instead of the current diversity tag that applies to a wide range of classes, Yen believes students could benefit from an overarching background course, just like how all SFS students take “Map of the Modern World” for a crash-course in geopolitics.

Yen explained it is important that an updated diversity requirement does not just reference marginalized groups within the curriculum but centers discussions on race and racism. According to Yen, the original group of students who helped establish the diversity requirement imagined just that. They pitched a “Problem of Race” course to discuss racial identities, Georgetown’s history of racism, and lived experiences of current people who hold marginalized identities on campus.

She thinks a university-wide required class would help foster necessary, but under-prioritized, discussions. “I think a small course that introduces every student to social identities, the cycle of socialization, and structures of power would help our campus have less polarizing conversations about identity.”

Such a course would benefit student discussions about race, Yen believes, with properly-trained faculty facilitators who could ensure conversations center the viewpoints of students of color without placing unnecessary burden on those with marginalized identities.

But there are also opportunities for those discussions to go beyond an introductory course. Yen agrees—bringing professors of color to Georgetown and building out ethnic studies are crucial next steps. “The most transformative classes I’ve taken are those that have specifically focused on the experiences of marginalized peoples, like ‘Asian American Lit’ or ‘Race and Politics,’” Yen said, also calling for emphasis on Indigenous Studies in the curriculum.

Moving forward, Doyle emphasizes that student voices are key to effective, anti-racist curricular development. Her advice to the administration: “[Listen] to what groups of students have repeatedly called for over the years.”

Adabala hopes that diversity and anti-racism efforts become inherent to every class’ development. “Hopefully it gets to the point you don’t even need a diversity requirement because it is naturally and seamlessly integrated into every course,” Adabala said. “Diversity is a part of your curriculum.”