Located at the intersection of Mt. Pleasant Street and Kenyon Street, “La Esquina” is always full of laughter, Spanish, and 7/11 coffee. For over 30 years, Salvadoran day laborers, nicknamed esquineros (men of the corner), have flocked to this vacant corner lot to play checkers with bottle caps and catch up about life.

As Mount Pleasant gentrified, the future of their paved oasis seemed uncertain. They didn’t have as much of a say as the new residents—most could not even vote, as non-citizens—but they feared development coming to the corner and pushing them away. So last October, community advocate Arturo Griffiths and Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne Nadeau got the corner lot officially designated as Amigos Park. It was a small win, but a meaningful one.

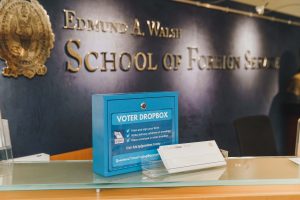

Now, Griffiths and Nadeau are part of an effort to give the whole immigrant community something much larger: a path to the ballot box. The Local Resident Voting Rights Act of 2021 would allow D.C.’s non-citizens—including undocumented immigrants—to vote in local elections. After almost a decade of discussion, it looks set to become a reality. But one question about the bill remains: Will the city invest what it takes to minimize potential dangers?

The idea was first proposed to the council in 2013 by Mayor Muriel Bowser when she was a Ward 4 councilmember. None of the previous versions of the bill passed committee, making last month’s unanimous approval a groundbreaking step nine years in the making.

Just one week later, on Oct. 4, the whole council voted on the bill, passing it 12-1. On Oct. 18, the bill passed the council a second time, unanimously, and as of the time of publication, it awaits Bowser’s signature to officially pass. Congress then gets 30 days to veto before it takes effect—one such veto bill has already been introduced in the House, but is unlikely to pass.

International students with F and J visas do not meet the residency requirement unless they’ve been in the country for more than five years. However, the bill would apply to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipients. TPS applies to immigrants from countries like El Salvador, with 30,000 in the region, and Venezuela, one of the main countries from which the immigrants recently bused to D.C. came.

Griffiths, who coordinates the DC Immigrant Voting Rights Coalition, brought his friend Soledad Miranda when we met for our interview, just half a block from Amigos Park. We sat down at a window table at Ercilia’s, a Salvadoran restaurant where they seemed to know everyone. After I assured Miranda that sí, hablo español, she told me that her first job when she made it to D.C. was at Georgetown. “I was a cleaner,” she said between sips of horchata, “at the bookstore.”

Miranda’s been in Columbia Heights for nearly 29 years, longer than the Metro stop or the shopping mall that have reshaped—and gentrified—the neighborhood. Because she came here from El Salvador without documentation, though, she’s never been able to vote.

“In all this time I’ve been here, I’ve been learning that we the immigrants, the politicians just use us. Solo promete. Prome, prome, prome. Y not doing nothing,” Miranda said. She’s tired of these empty promises and eager to have her voice heard at the polls.

With the vote, non-citizens can finally shape the issues that matter to them, like housing, and can elect people who represent and stick up for them. “They’re not going to be dormant anymore,” Griffiths said. He knew the feeling well: Having immigrated from Panama in 1964, Griffiths only gained citizenship—and a vote—10 years later.

“I remember when I first stepped into the ballot box, I couldn’t speak that much English. So I had problems,” Griffiths said, laughing. “They weren’t giving Spanish ballots. I didn’t know exactly who to vote for, but I didn’t see anybody that represents me running for office.”

“But it was a great experience. I kept learning and kept voting, and I’ve voted ever since.”

If the city doesn’t ensure these first-time voters are well-informed, though, the very act of voting presents a risk. Since D.C. is a federal enclave, local elections and federal elections happen on the same day and ballot. For an undocumented immigrant, attempting to vote federally is seen as misrepresenting your citizenship status—a deportable offense.

Abel Nuñez, the executive director of Central American Resources Center (CARECEN), opposes the bill because of the possibility that these new voters will make a dangerous mistake on their ballots. He said he raised this concern in a committee hearing in July.

“If even one person makes a mistake, it’s one too many,” Nuñez said. “I don’t believe the benefit of voting outweighs the dangers.”

A Board of Elections representative said at the hearing that they plan to implement a new system in which voters identify themselves and are given either a citizen or non-citizen ballot. Still, Nuñez said he didn’t feel comfortable with the risk of error.

Nuñez also said he didn’t want to add fuel to the right-wing, anti-immigrant fire responsible for sending buses full of migrants to the District, especially if the bill might only be progressive posturing, without risk-prevention measures to make it safe.

“Is this a vote to make us feel better that we’re giving people the right to vote? Or is it a true benefit, and we’re going to invest in educating people,” he said.

Many in the Georgetown community would be affected by this bill, from workers to students to staff, like Juan Belmán, who works at the Kalmanovitz Initiative and on the university’s Undocumented Student Advocacy Coalition. Belmán is a DACA recipient, and said he’d be excited to vote.

“But I would also be very careful, like study everything legally to make sure I wasn’t, you know, breaking any laws in terms of federal voting,” Belmán said.

Jenny Park (COL ’24), the programming director for Hoyas for Immigrant Rights (HFIR), said the bill has HFIR’s full support. She noted that many undocumented Hoyas already study or organize around immigration rights.

“Being able to act on that by voting is going to be really empowering,” Park said. “It’ll help highlight those voices in the community.”

Miranda said she sees the bill as a win. However, she doesn’t think it’s going to erase the gap between native-born citizens and undocumented immigrants like herself and many of her friends.

“You will have your choice of where to live, what to do, and we do not have that opportunity. So, we will still have to come and cook, and clean, while the university students are in the office on the computer,” she said, pretending to type on our table in Ercilia’s. “It’s different.”

Griffiths swallowed his food and cut in, reaching out as if to pat me on the back reassuringly. “It’s okay! We still like you guys.”