In 1912, sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder made a statue of a Sioux man, wrapped in a blanket, gazing inscrutably into the distance. The work, titled “An American Stoic,” was emblematic of prevailing depictions of Native Americans—the centuries-old trope of the silently suffering “noble savage” was personified in the subject’s solemn posture and blank expression. By painting Native Americans as passive victims, such portrayals contributed to the stripping of Indigenous agency, a troubling artistic tradition that persists in the nuance-lacking, excessively violent tone of Martin Scorsese’s latest film, Killers of the Flower Moon (2023).

For the majority of Killers, a tragedy based on a true story, actor Lily Gladstone operates in much the same mode as Calder’s muse. She plays Mollie Kyle, an Osage woman, in the years following “An American Stoic,” with a seemingly serene affect—even as her community is methodically decimated. As the film progresses, it’s only thanks to Gladstone’s stellar acting that we begin to see cracks in an otherwise unmoved, emotionless facade.

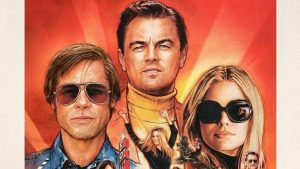

While certainly the film’s most interesting character, Mollie unfortunately isn’t the protagonist of Killers—rather, that title belongs to her husband, Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio). Ernest is a trusting, tactless, and sickeningly opportunistic veteran who, under the guidance of his equally opportunistic—but much savvier—uncle William Hale (Robert De Niro), defrauds and murders Osage Natives in a cruel get-rich-quick scheme in rural Oklahoma.

By following the story’s villains, Scorsese ostensibly seeks to subvert conventional storytelling techniques and explore unexpected perspectives; however, centering white men in a story about Native Americans is actually the most unoriginal choice. This approach doesn’t pay off, and instead, Killers lands as an unnecessarily graphic caricature of Indigenous suffering.

The film opens with a windfall (and death knell) for the Osage. As community elders perform a burial for a ceremonial pipe, velvety black oil spurts out of the ground; quickly, the narrator explains, the Osage become the richest people in the world. Sensing an opportunity, grifters like William and Ernest plot to access this wealth by covertly amassing headrights, which enrich Osage shareholders.

But in its disjointed narration of the mechanisms of this racket, Killers sacrifices narrative cogency and respect for the Osage victims. For the first few hours, the movie focuses on the web of lies and atrocities Ernest envelops Mollie in. At his uncle’s urging, he courts and marries her, but slowly, Mollie’s relatives begin mysteriously dying—only after Ernest arranges their headrights to pass to Mollie, and eventually to him, upon their deaths—and Ernest’s role in the murders becomes increasingly clear. As the walls close in on Mollie, Killers feels like an unrelenting barrage of the Osage being manipulated, mutilated, and plunged into immeasurable grief.

As the film nears the end of its astounding three-and-a-half-hour runtime, however, it can’t quite choose an identity, flitting indecisively between cinematic styles. Once the case enters the courts, Killers shapeshifts into a procedural drama about the legal system, especially as it traces the emergence of the FBI as a sophisticated crime-fighting institution. And then suddenly, in the film’s waning minutes, Scorsese introduces a metanarrative in which the whole story is recounted in an old-school true crime radio show. If Killers had chosen just one of these lenses and introduced it early on, perhaps through flashbacks (à la Oppenheimer [2023]), it would have provided much-needed framing to an engrossing but unstructured film.

Killers’s one deviation from its strictly chronological structure is perhaps its most egregiously misused narrative element. During the courtroom testimony of a hitman responsible for one of the murders, we hear, in gruesome detail, how exactly it was carried out. Audiences had already been subjected to a graphic shot of the autopsy, sensationalized as a public spectacle for the townspeople, and the logistics of the killing itself hadn’t seemed relevant to the plot. But then, just as the testimony begins to feel excessively comprehensive, Killers cuts to its only flashback, where we then have to watch the same murder we’ve already heard far too much about. As if the atrocity of the death wasn’t enough on its own, the film rehashes it three times.

During the rare moments when the film focuses on the Osage victims’ experience, its overemphasis on physical brutality feels like a disrespectful use of violence. Killers reduces their suffering to shock-value-garnering gore, echoing a long history—from 19th-century vaudeville shows to Hollywood’s Westerns—of exploiting violence against Indigenous bodies for white viewers’ entertainment.

For what it’s worth, Scorsese gleans superb performances from his cast. Gladstone captures every inflection in a role written as a one-dimensional vessel of ceaseless suffering (like all of Killers’s Osage characters). Teasing out the nuances in Mollie’s stone-faced endurance of physical and emotional pain, she also brings explosive, heart-wrenching feelings to the few scenes where Mollie vocalizes her rightful rage and grief. By contrast, the script works fervently to humanize Ernest, highlighting his own victimhood at the hands of William’s abuse and his ongoing moral dilemma as he weighs his supposed love for his wife against his desire to gain money and appease his uncle. The role is perfect for DiCaprio, who has effectively built a career of playing bad guys with complex motives, and he pulls it off once again.

It’d be misguided to expect Scorsese to shy away from the inherent violence of the subject matter, but one would hope for a more sensitive, tactful approach, especially with the power dynamics at play whenever white filmmakers tell Indigenous stories, from the lack of opportunities for Native American filmmakers to the persistence of stereotypes and cultural inaccuracies. Given Hollywood’s longstanding disinclination toward Native American protagonists, centering Killers around Mollie could have afforded the film both a new perspective and much-needed direction. While Killers showed snippets of Mollie’s efforts to fend off the murders, for instance, only a film with her as its focus could have done her story justice.

Killers illuminates an overlooked history, and notably, Scorsese consulted with Osage leaders—a step in the right direction. But ultimately, the film still sees a white director prioritizing the perspective of a white perpetrator, a reality that N. Bird Runningwater, director of the Sundance Institute’s Indigenous Program, characterized as “encroachment.” Hollywood should heed the advice of a white doctor in Killers who, when trying to shirk the FBI’s interrogation, ironically said it best: “This is Indian country—go talk to the Indian.”

Get your facts straight