My mother—or as I call her, Mamu—gave birth to me in a hospital on the outskirts of Philadelphia. It was the dead of winter, and as she claims, the late-February snowstorm rattled the hospital windows.

“As soon as you came out, the skies cleared up a bit,” Mamu told me. I can never tell if this part of the story is true.

What was true was that the hospital room was swimming in an ocean of my family. Having three generations of people in a confined space seemed trivial, yet looking back, it was a sacred experience. Mamu’s mother—my grandmother—never left Mamu’s bedside: she held Mamu’s hand and, in the same gesture, extended her finger to hold my newborn hand as well.

For the next year, my grandmother lived with my family to help raise my sister and me. Her gentle touch and her kind eyes grew familiar, so much so that I would often mistake her for my Mamu. It only made sense that my first word was addressed to her: “Aama,” which in Nepali, means “mother” and not “grandmother.” She wore the title proudly, like a pageant sash.

I’d like to think this was the beginning, that the first word that spilled out of my mouth was in my mother tongue—a phrase dedicated to the woman who meant the most to me, yet I called her the wrong name.

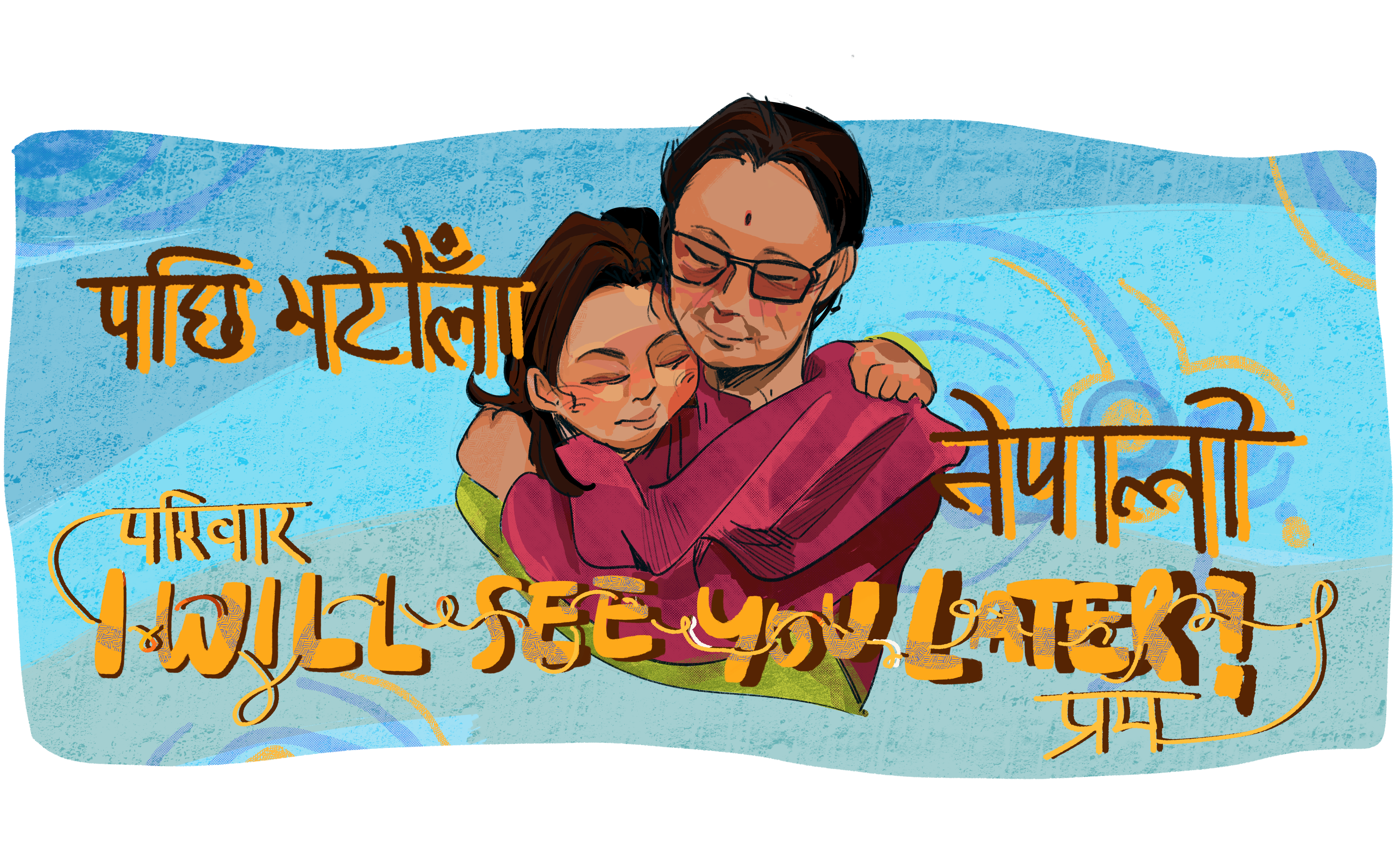

This is a story about words: the ones that were shared, others that were lost in translation, and some that never needed to be spoken aloud.

***

As I grew older, Aama taught me new Nepali words. Eventually, the words I used to communicate to her grew exponentially—as did my hesitancy in saying them.

At 4, she asked me what I ate for dinner that night, and I replied in Nepali: “I eat … rice and … umm, chicken,” and she laughed because I forgot how to say eat in past tense.

At 12, she asked what I was studying in school, but I did not know what the Nepali word for science was—so after pausing for a few seconds too long, I let out a defeated sigh and just responded in English. She nodded, but I could tell she did not understand.

At 16, I spent the summer with her in Kathmandu. During my last day when it was time to say my farewells, I paused—not just because I did not want to leave her, but because, in the recesses of my brain, I could not find the right words to tell her how much she meant to me.

My proclamation of love for Aama fell short; I could not even find the Nepali word for goodbye, so instead, I said: “I will see you later,” hoping that she could accept this farewell.

There were regrettable days that I put off FaceTiming her out of sheer anxiety of having to speak in Nepali again: “I’ll call her in a few days,” I told myself out of habit.

“In a few days”—a mantra for those, like me, that leave things to the last minute. It took me too long to realize that my grandmother, a 72-year-old with three failing organs, could not afford that luxury.

***

The truth is, inarticulately speaking a mother tongue felt so familiar yet simultaneously so incomplete and distant. At times, trying to find the right words felt like scraping each corner of my mind for imperfect puzzle pieces; trying to formulate a cohesive sentence felt like an insurmountable task. Each forgotten word felt like a letdown to Aama.

Yet, she never understood my disappointment. She continued teaching me the Nepali alphabet and correcting my grammar whenever I misspoke. She viewed every new word and every clear sentence with pride—and treated every hesitation and every nonsensical phrase with lightheartedness.

Despite our language barriers, we understood the love we carried for each other. With every sarcastic one-liner from her, there was a joy in the laughs we shared. During every card game, there was a tenderness in the time we spent together. With every warm embrace, there was a nonverbal consensus of devotion.

Eventually, Aama got sicker. Despite being unable to accept it, I knew rationally that her congestive heart failure could not be cured. She was dying. But even when her movements became slower and words became fewer, she spread her unconditional love like seeds—and every room she entered blossomed with her presence.

The last time I saw her was in early August—two weeks before she died—bedridden at the critical care unit: an image imprinted in my mind. As much as I was laced with regret at the moments I chose not to speak Nepali to her, I was simultaneously in awe of her resilience—and her community. During times of great despair, I saw how loved Aama was, for the hospital room was swimming in an ocean of my family. Having three generations of people in one space was, in fact, a sacred experience.

I learned, then, that love and hope are somehow intertwined with grief and anger.

Anger and guilt bubble up within me still because I am angry that she was taken from us so soon. I feel guilty for not having spoken Nepali to her every chance I had.

Yet, I am also struck with gratitude for all of the small moments we shared and the choppy sentences I said to her. Some day, my children will meet a version of Aama because her legacy lives on in me. Amidst the cacophony of our language barrier, the cup of love she poured for me is overflowing.

***

The Saturday before the fall semester started was the last time Aama and I spoke. At this point, she was on powerful opioids to help with her pain—hallucinating and mostly nonverbal—and I was trying so hard to hold back my sobs that I could not find the courage to tell her, “I love you.”

Between the heavy breaths and teary eyes, I realized I had still not learned the word for goodbye. So, I said nothing. As I was about to leave, I heard a familiar voice: “I will see you later,” Aama managed to say in her drug-induced state.

At that moment, I felt content not knowing the word for goodbye because, yes, I will see her later. And yes, I am so lucky to be Aama’s grandchild—this feeling even stronger after she is gone.