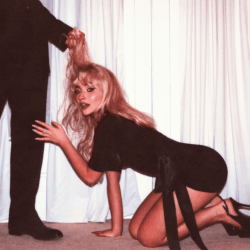

This summer, I worked for Ms. Magazine and became a bit of their “unofficial official” Sabrina Carpenter Correspondent, as well as all things pop and sex. Naturally, the Man’s Best Friend (2025) album cover controversy, in which the internet flew into debate over Carpenter’s submissive sexual imagery, continues to be high on my radar.

As Leisure’s Lucy Montalti astutely explained in her review of the album, “With such intense backlash, many were hoping that the album itself would contextualize the cover and title,” but ultimately, “It isn’t a grand, radical manifesto about sexual freedom, nor is it a full-blown degradation of Carpenter’s dignity as a woman.”

I agree that Carpenter does not present a critical thesis with her art. Instead, I believe she just enjoys expressing sexuality through her work (and has a fun knack for dick jokes). However, I think that the controversy itself merits discussion beyond the music, primarily because it interrogates our current culture of sexual liberation and to what extent we are “allowed” to be uncomfortable without shaming female sexuality: this becomes especially critical when violence is at play.

Carpenter’s album art caused an undeniable backlash, arguing that the cover’s extreme sexuality was degrading to women. Indeed, the depiction of Carpenter on her knees, pawing at a faceless man, who holds her hair like a leash—imagery that alludes to violent or more aggressive sex—was a distinct departure from her light-hearted, sex-positive rhetoric. “How is this not just appealing to the male gaze?? insanely misogynistic imagery,” one X commenter complained. Others suggested that the album art was endangering women’s safety by glamorizing their submission to straight men. “‘why do u care what straight men think?’ i care about my safety and i care if we are being over-sexualized thank you,” another user wrote.

Despite the reaction she triggered, Carpenter is not quite breaking barriers with her art, especially considering her predecessors. A 2024 Rolling Stone article titled, “Sabrina Carpenter to Critics Shaming Her Sexual Embrace: ‘Don’t Come To The Show,’” dubs Carpenter a graduate of “the pop star school of Christina Aguilera and Britney Spears.” Indeed, Carpenter rivals the raunchiness of both Aguilera and Spears. Spears’ “I’m a Slave 4 U” (2001), provocative enough with its title, is known for its equally salacious and iconic snake dance. As for Aguilera, her song “Genie in a Bottle” (1999) invites her listener to “rub her the right way.”

I would wager to say that Carpenter hasn’t upped the ante in comparison to these ’90s-’00s superstars; if anything, she’s just gotten more casual. Her innuendo is no more fiery or tempting than what listeners may hear at a frat house. Her song “House Tour” plays with the predictable metaphor of “I just want you to come inside,” which is more of an easy laugh than a flirty line. Unlike her predecessors, who glaze their sexuality with mystery and temptation, Carpenter is probably one of the first female artists to come right out and sing, “I’m so fucking horny.”

Carpenter’s playful and confidently effortless approach to sex perhaps signifies a newfound agency women have gained over their sexuality. Carpenter is a product of the ’90s-’00s, a particularly grueling time in which sexual exploitation, masquerading as liberation, completely dominated these women’s careers. Atlantic writer Sophie Gilbert, in her article titled “What Porn Taught a Generation of Women,” writes that women during the ’90s-’00s were objects of constant exploitation. “So much of this century’s popular culture,” she asserts, “has presented women as spectacles: chaotic, melodramatic, hypersexualized recipients of attention.” Control is the key factor here, and control is ultimately what female pop stars lack.

By comparison, Carpenter’s blunt, straightforward sexuality tells us that she’s in on everything. She knows exactly what she’s doing. She’s in control.

And yet, when she released an album cover that she most likely developed herself, people called her decision degrading and disempowering. Strange, considering that Spears’ “I’m A Slave 4 U” is lauded as iconic and yet all about sexual submission. Clearly, the backlash is a product of our generation.

In a recent interview with Gayle King, Carpenter responded to the album cover controversy with some simple advice: “Y’all need to get out more.”

And according to some recent polling, we do. Gen-Z’s “sex crisis” has been quite the hot topic of the summer; New Yorker author Jia Tolentino, in her article titled, “Are Young People Having Enough Sex,” cited a study from 2018 in which, “a survey of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds found that nearly a third of the men in that group, and about a fifth of the women, had gone without sex for a year—a significant jump from the numbers in the early two-thousands.”

In NPR’s podcast “It’s Been a Minute,” reporter Britney Luse cited this sexual recession as the basis for Carpenter’s cover art backlash—which was reportedly mainly Gen-Z driven—claiming that young people are simply afraid of sex.

During the episode, Carter Sherman, reproductive health and justice reporter, disagrees, challenging the notion that young people are lacking sexual experience. “I would say that they are in general not less horny,” Sherman explains, “I think what they are doing, though, is outsourcing a lot of their sexuality to the internet. They’re watching a lot of porn.”

Indeed, we are a generation saturated in porn, which inevitably pushes violence as a core element of sex. Statistically, a content analysis of the best-selling pornography finds that 88% of scenes portrayed physical violence (e.g., spanking, gagging, and slapping).

Despite this saturation, it seems that for young people, violence is at the core of the album art’s discomfort—perhaps because it continues to push a dangerous sexual agenda that we are all too familiar with.

And yet, Carpenter’s defenders insist that she is, if anything, pushing against the misogynistic agenda of porn, making a feminist statement by subverting visions of sexual empowerment. As in, without a message, the image would be upsetting.

Gen-Z is at a really odd place with sex. We both have more agency to explore—as sex has naturally become less taboo and more openly spoken about—and subsequently feel compelled to validate all sexual kinks for fear of seeming prudish, all while wrestling with power dynamics that conflict with intimacy.

We’re not immune to gendered power dynamics, and it can be scary to think they creep into some of the most intimate parts of our lives. But that doesn’t mean we need to be comfortable with them to have agency over them.

Carpenter’s sexuality is ultimately what she makes of it. Listeners may never know what the provocative album cover truly means. But media representation matters, whether the message is intentional or not, and especially with topics as intimate and influential as sex. We should listen to how we feel about the media that makes us, and sit with our discomfort rather than scrambling to justify the feeling. Violence is instinctually upsetting, and I think that’s true for most of us. That can still be the case whether you choose to agentfully explore it or avoid it.