We’ve all seen the swoosh. From the T-shirts we wear at games to the jerseys our Hoyas don on the hardwood, Nike has a significant imprint on the brand of Georgetown University. Since the days of Patrick Ewing and the height of the Big East Conference in the early ‘80s, the University has maintained a partnership with Nike.

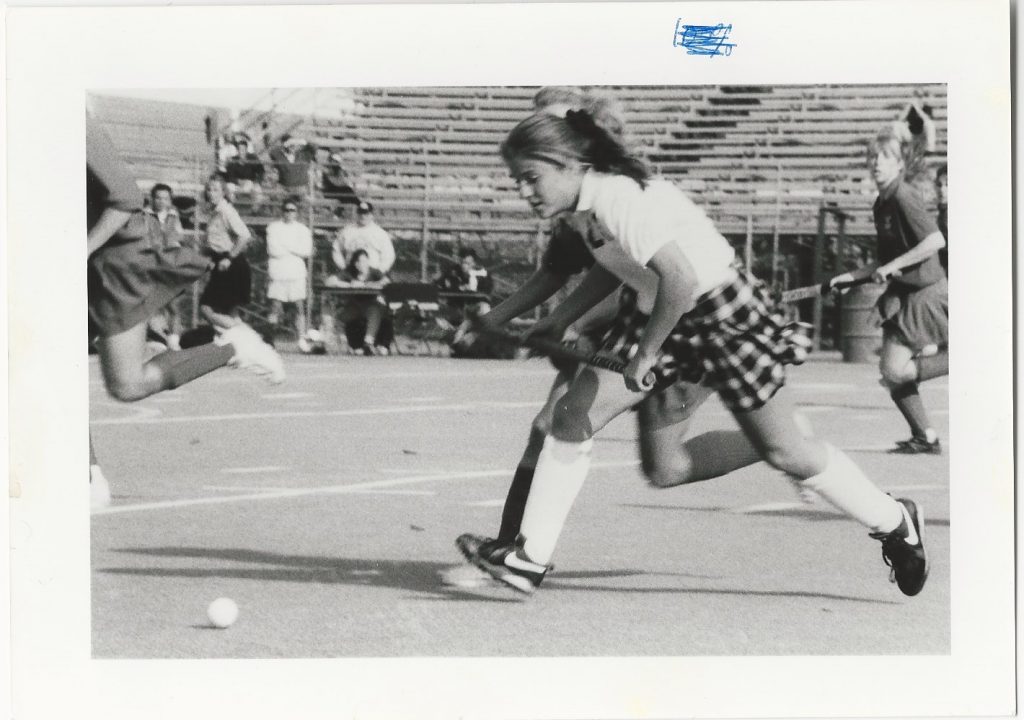

Georgetown Field Hockey / Voice Archives

In the last two decades especially, that relationship has come under fire both from within the Georgetown community and throughout the country, as knowledge of Nike’s widespread labor abuses has spread. Universities, some of the largest consumers of Nike apparel, have aided in the formation of groups such as the United Students Against Sweatshop Labor (USAS) and the independent labor-rights organization Workers’ Rights Consortium (WRC), ushering in a new age of transparency for the apparel industry.

However, Nike’s recent decision to no longer allow the WRC access to its factories and their noncompliance with Georgetown’s Code of Conduct’s policy on living wages has raised some questions. A presentation on campus in November and a subsequent small protest by a group of athletes has sparked a renewed conversation on Nike’s labor violations. Why is Nike permitted to stay on as an official merchant of Georgetown apparel, let alone the exclusive apparel provider of Georgetown Athletics, if they do not align with the University’s core values? Could Nike’s special history with Georgetown play a role in its treatment? What is the future of Georgetown’s checkered history of student activism against labor rights abuses?

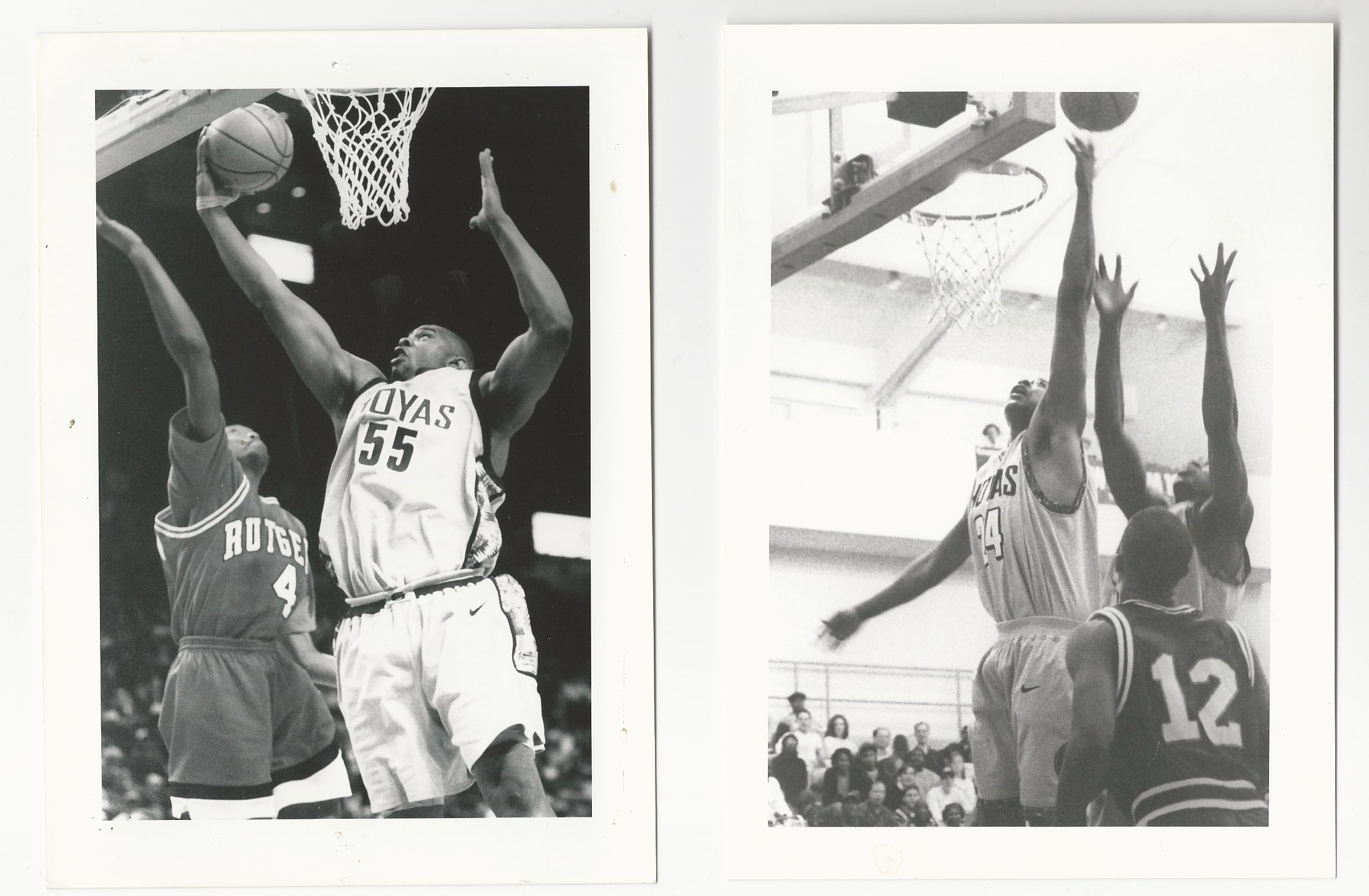

Basketball and the Georgetown Brand

The “branding” of Georgetown can be traced back to the early 1980s, when the university joined the new Big East Conference. The men’s basketball team enjoyed unprecedented success throughout the decade, reaching the Final Four of the NCAA Tournament three times and winning a national championship. Not surprisingly, Georgetown University’s national profile skyrocketed during this time period, as shown by a 45 percent increase in applications to the school during the three years that Patrick Ewing spent on the Hilltop, according to Forbes.

Georgetown and Nike also began their partnership in the early ‘80s. This relationship has grown stronger since, according to Dan O’Neil, Senior Associate Athletics Director for External Affairs. Nike has been the exclusive apparel provider of Georgetown Athletics, and provides “uniforms and performance items for all 29 of Georgetown’s intercollegiate athletics teams,” he wrote in an email to the Voice.

Through its basketball program, Georgetown has formed deep ties with Nike. These go beyond mere cultural association, as evidenced by Former Head Coach John Thompson Jr.’s position on the Nike Board of Directors.

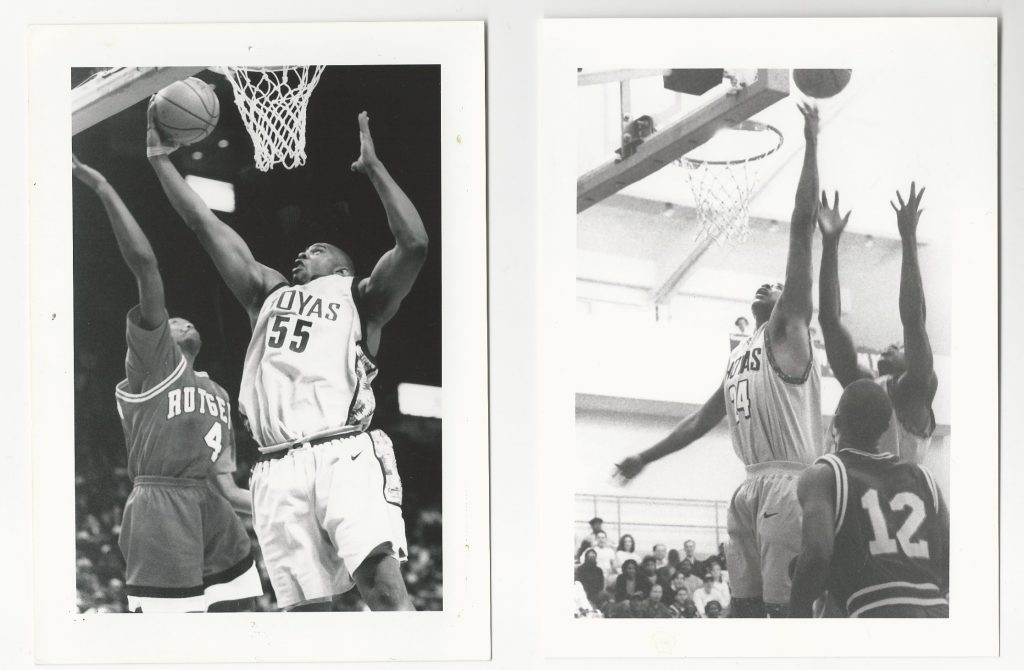

Georgetown Men’s Basketball / Voice Archives

Both Thompson Jr. and current Head Coach John Thompson III declined to comment for this story through a spokesman.

Student Activism for Labor Rights at Georgetown and the Question of Nike Sweatshops

While Nike and Georgetown basketball go hand in hand, Nike’s history of labor violations serve as a rarely-examined subtext to the relationship.

Professor John M. Kline of the School of Foreign Service, who sits on the board of the university’s Licensing Oversight Committee (LOC), believes that student engagement in these issues is the catalyst in achieving success. The collegiate apparel industry, he pointed out, has seen improvements in workers’ rights because its consumers are the most civically engaged.

“Unless there is student interest on the issues, things can go on for a long time without any kind of action,” Kline said. “The LOC exists because the students were engaged in that issue and considered it important. Student involvement is essential. It ebbs and flows. I don’t think the last few years have been as engaged as prior years. It seems to be picking up again, and I’m all for that.”

Since Georgetown joined a growing national trend of student protest against sweatshops in the ‘90s, student engagement in issues of workers’ rights has helped to shape the relationship between Nike and the school.

“This whole sweatshop thing began in Duke University, and Georgetown was one of the second or third universities to have student protests against the administration, trying to get them to adopt a uniform code,” said Kline. “There was cooperation with other universities in doing this.”

A wave of sit-ins was held at 100 campuses across the U.S. under the umbrella organization USAS in 1999, as was reported by The Guardian. “We will not allow our universities to profit from the sweat of inhumane conditions and the suffering of worker mistreatment,” USAS said.

Twenty-seven Georgetown students held a sit-in for 85 hours in the office of President Leo J. O’Donovan, S.J. The Georgetown Solidarity Committee led the protest, demanding full disclosure of factory locations of companies producing Georgetown apparel.

The agreement between the protesters and the Georgetown administration led to the establishment of Licensing Oversight Committee in Fall 2000, and the creation of the Code of Conduct for Georgetown University Licensees.

The establishment of new parameters in Georgetown’s relationships with its licensees, including Nike, was concurrent with the formation of a new national infrastructure for labor rights monitoring.

“There was actually a White House group that was formed to try to address the sweatshop issue. Out of that came a group called the Fair Labor Association (FLA), and that is comprised of the brands and universities, no students,” said Kline.

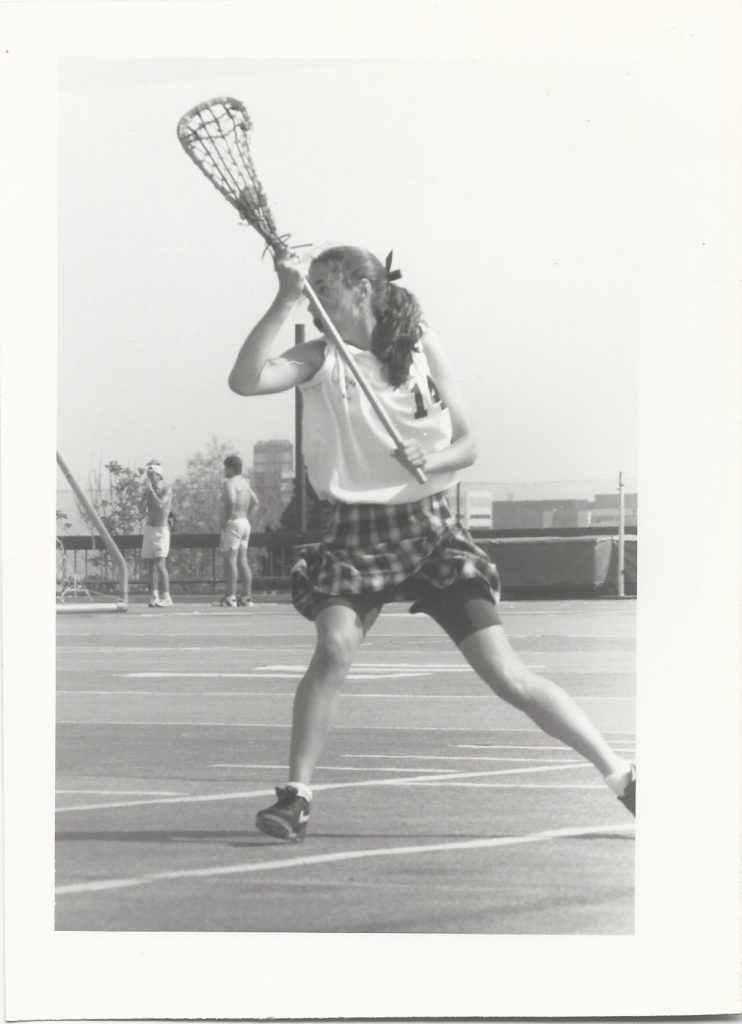

Georgetown Women’s Lacrosse / Voice Archives

According to Kline, the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC) was created in response as an alternative to the FLA, out of a concern that the FLA’s brand members would affects its neutrality. “Georgetown is one of the universities that is only a member of the WRC. There are universities that are members of both. So WRC was pretty much a student creation. And it’s just the students and universities; there are no corporate members in WRC,” explained Kline.

“My understanding is that FLA is more integrated with Nike, such as in terms of funding and governance whereas the WRC is more independent,” Justice and Peace Studies Professor Eli McCarthy said.

The most recent issues at hand in Nike’s relationship with Georgetown are Nike’s refusal to allow the WRC entrance to its factories in fall 2015 and its refusal to commit to a living wage for all its factory employees.

Code of Conduct

Isabelle Teare (COL ‘17) is a member of Athletes and Advocates for Workers’ Rights, an organization that works to raise awareness about the treatment of workers in sweatshops. She questions whether the strength of Georgetown’s ties to Nike have influenced Georgetown’s decision to keep Nike its sole provider of apparel, despite its treatment of workers.

“Every licensee of Georgetown, so everyone in the bookstore, is required to sign Georgetown’s Code of Conduct,” says Teare. “Nike is the only outside contractor that we do not require to sign our Code of Conduct … Why are we holding Nike to different standards than we hold the rest of the people who are making our university apparel?”

In a letter received by the WRC on Oct. 29, 2015 and quoted in correspondence from the Consortium to its affiliated universities, Nike detailed its decision to block the WRC’s access to Hansae Vietnam, a factory that produces collegiate apparel for for the company.

“Nike has a rigorous due diligence and criteria-assessment process to determine third party auditors, through which representatives of the Fair Labor Association and Better Work have been approved to conduct audits of those contract factories manufacturing Nike product,” said the letter. “However, Nike does not permit other third parties to conduct such assessments.”

Hansae Vietnam was the site of a worker-led strike in March 2015, where factory workers protested unsafe working conditions. Teare is concerned about the precedent this sets. “Nike has a problem right now because they aren’t allowing third party monitoring,” says Teare. “That’s an issue because if Nike, which is a massive leader in the industry, all of sudden says ‘We don’t want to let people in,’ … [it could] start a ripple effect that’s moving backwards.”

The Role of the Licensing Oversight Committee

“Georgetown established the LOC in 2000 to provide guidance to the University’s leadership regarding trademark licensing policy. The LOC meets regularly and includes student, faculty, and staff representatives,” Cal Watson, the chair of the LOC and Director of Business Policy and Planning, explained in an email to the Voice.

“The LOC has met several times to discuss the recent concerns that have been raised about Nike. Georgetown has been engaging with the WRC and Nike regarding these concerns. Those conversations are ongoing,” said Watson.

Lillian Ryan (COL ‘18), an undergraduate member of the LOC and the student group Georgetown Solidarity Committee (GSC), said the LOC serves as a connection between worker’s rights and larger institutional goals. “[The LOC relates] worker’s justice to broader institutional goals, trying to hold the university accountable to its own standards of social justice.”

The LOC has played a critical role in the direction of Georgetown’s relationship with other apparel licensees since its establishment. In 2009, under pressure from the GSC, the LOC decided not to renew Russell Athletic’s contract after an investigation into Russell’s labor practices.

In 2012, the LOC recommended that Georgetown drop Adidas due to its violations of the Code of Conduct. This resulted from a combined pressure by the LOC and student groups like the GSC. “It was both the Licensing Committee and the Solidarity Committee who were involved in trying to pressure Adidas to work on their labor standards,” said Ryan.

These examples of the LOC’s enforcement of the Code of Conduct demonstrate its role in maintaining accountability, but Kline points out that removing licensees due to violations is not the goal.

“The effort is first made to try and solve the problem. So if the workers have not been paid, then you want them to be paid. You try to resolve that issue. If you cancel the contract, that doesn’t give the workers any money. So canceling the contract is a last step when you realize the brand isn’t going to be responsive,” he said.

It’s Not Just Nike

Nike is hardly the only corporation to come under fire for its treatment of workers.

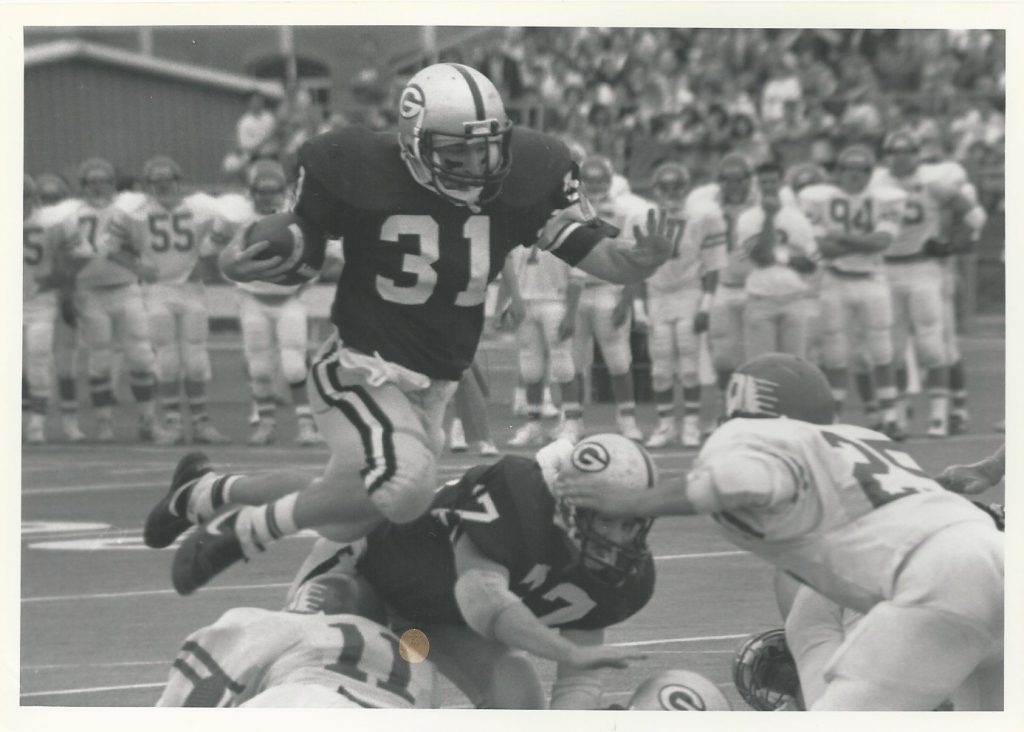

Georgetown Football / Voice Archives

“They all have labor abuses, and that’s where it gets really hard. You have to start somewhere,” said Teare. “We want to keep moving forward, not backward, and what Nike’s doing right now is trying to take a step backwards.”

According to Kline, Nike has set a good example for others in the industry with its progress so far, but that example will be negated if it continues on its recent trajectory reversing away from transparency in the past year.

“I have a lot of respect for Nike in some of the leadership positions it has taken,” says Kline. “It was the first one to disclose factory locations, after saying they never would. It has taken steps in several of the cases involving Georgetown … to provide money to compensate workers who hadn’t been paid by the factories that closed … So they have pretty good standards, they do a good job.”

But without the system of checking and monitoring the company’s practices that came about in the 1990s, advocates worry that their progress will halt.

McCarthy believes that Nike’s position of leadership within the apparel industry make its labor practices especially important.

“Nike continues to fail to pay workers enough to meet their basic needs such as both food and school for kids. Nike also continues to harm workers and communities with the large toxic piles of scrap shoe rubber. The formation of unions also remains difficult in some areas,” wrote McCarthy in an email to the Voice. “Nike has by far the largest market share of this industry. This is why it is so important to address their abuses not only for their workers but also for industry standards that impact thousands of other workers.”

Georgetown Women’s Soccer / Photo: Georgetown Sports Information

Alta Gracia

Kline believes that while protests against Nike’s practices are necessary, a movement also needs to include uplifting ethical apparel companies. He cited Alta Gracia, an apparel company that provides a living wage to its workers, as an example of a company more worthy of support. Kline conducts research on Alta Gracia though the Reflective Engagement Initiative.

According to an Employee Wage Cost Comparison included in a Research Progress Report on the company by Kline and MSB Professor Edward Soule, an adjusted living wage rate for Alta Gracia employees was over 350 percent higher than the minimum monthly wage in the fair trade zone (FTZ) in the Dominican Republic in November 2011. The cost of maintaining this living wage within the context of an mega-industry fueled by cheap labor is a serious disadvantage, meaning that Alta Gracia’s success depends on the support of its collegiate customers, the report said.

“I think that Alta Gracia is the best thing that has happened to the collegiate apparel sector since they adopted clothes in the monitoring process,” said Kline. “With a little bit more money, not that much more money, we could be supporting Alta Gracia. We could be working with other student groups at other universities to support it.”

Kline and McCarthy see both protesting violations and supporting companies like Alta Gracia as ways for students to drive an examination of Georgetown’s relationship with Nike.

According to Kline, though, movements of support are sometimes undervalued components of student engagement with labor rights. “What I’ve noted is that it’s frankly easier to get the students interested and motivated when there’s something you can protest about,” wrote Kline. “I think what’s important is using complementary methods to try to reach a goal,” Ryan agreed, speaking both as a member of GSC and an LOC member.

“Ultimately though, the students must discern, ideally with the workers, the greater good and the strategy to get there,” McCarthy said.

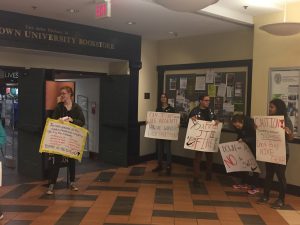

The Power of the Student Athlete

In his presentation at Georgetown, Behind the Swoosh: Sweatshops and Social Justice on Nov. 9, 2015, Keady argued that the student athletes are being used by both the Nike and the Georgetown brands. Keady believes that Nike uses Georgetown’s and other Catholic universities’ values as means to validate the Nike brand.

“Georgetown was used, and the administration and elected parties used the student athletes and continue to do so. They have turned [student athletes] into walking billboards for a company that violates everything this Catholic Jesuit institution stands for,” Keady said.

Photo: Jim Keady

A few student athletes taped-over the Nike swoosh on their athletic apparel following the presentation. According to McCarthy, the response to this single event demonstrates the power that student athletes have in the overall dialogue.

“When student-athletes simply covered their swooshes, some coaches and others pushed back. This is an indication of the potential power student action could have. I think student actions could play an even bigger, more transformative role in ensuring more just agreements for workers,” wrote McCarthy.

The power of student and athlete action to bring awareness to an issue was demonstrated in December 2014 when the Hoyas Men’s Basketball Team all donned “I Can’t Breathe” shirts, to protest police brutality in the death of Eric Garner. Thompson II bluntly offered his views on the subject of athlete and student engagement into these matters in a press conference after the game, saying “It’s a f—ing school, man. That’s your responsibility, to deal with things like that.”

Almost immediately after the game, the conversation switched from the 75-70 setback the team suffered to Kansas to the national message they conveyed by simply wearing a t-shirt. This offers a model for future activism that McCarthy envisions. According to McCarthy, taking action for labor rights is a basic imperative of Georgetown’s values.

“We should support our students in exploring how to transform such injustices and not get stuck ignoring them [or] downplaying them,” McCarthy wrote. “This is basic Catholic social teaching of human dignity, human rights, and the faith that does justice.”

Students and universities all have uniquely strong positions for ensuring workers’ rights. “Universities have the power because they choose to consume the goods and make a contract, so they can always withdraw this consumption. Thus, this power allows them to put pressure on Nike to ensure access to a particular monitoring agency. The stronger they make the contract the more they can ensure their impact, such as choosing the monitoring agency,” said McCarthy.

- Georgetown Women’s Basketball / Photo: Voice Archives

- Georgetown Women’s Basketball / Photo: Sports Information

- Georgetown Men’s Basketball / Photo: Voice Archives

- Alex BoydGeorgetown Men’s Basketball / Photo: Alex Boyd

- Georgetown Men’s Basketball / Photo: Voice Archives

- Georgetown Men’s Basketball / Photo: Tyler Pearre

Kline believes that it will take a continued effort to see more positive improvements. “Georgetown has played a leadership role in this whole issue for quite awhile. I’m hopeful it’ll continue to do so. But it will do so if it knows students are interested in it. That’s a necessary condition to keep interest for a lot of the rest of the university.”

“Right now, we’ve made some recommendations to the administration in terms of the Nike initiative. I’m very hopeful that the university will continue its past policies, that it will bring the agreement with Nike up to date, and everything will be good, said Kline”

“Ultimately though,” says McCarthy, “the students must discern, ideally with the workers, the greater good and the strategy to get there.”