In December, a new filing in the class-action lawsuit against Georgetown and 16 universities alleged that Georgetown’s former President John DeGioia created a yearly “President’s List” with the names of around 80 legacy or wealthy applicants. They were to be admitted without review of their grades or essays.

Some community members may have been shocked by these allegations. Unfortunately, I wasn’t. While often-secret mechanisms of privilege like a “President’s List” seem uniquely elitist and inequitable, I’d argue that the admissions practices Georgetown doesn’t hide are equally, if not more, disconcerting.

In an October press release sharing demographic data for the Class of 2028, the first admissions cycle since the end of affirmative action, Georgetown said the percentage of admitted students from historically underrepresented groups did decline from the year prior.

After the Supreme Court overturned affirmative action, DeGioia criticized the decision in a university-wide letter and reaffirmed Georgetown’s commitment to a diverse student body.

“Affirmative action was built on hope—the hope that we could be better in the future than we’ve been in the past. Georgetown embraced this hope. Now, we will need to find new ways of restoring this hope,” DeGioia wrote.

It feels like Georgetown hasn’t been looking very hard for those “new ways.”

For starters, Georgetown continues to practice legacy admissions, a preference for children of alumni, despite years of calls to end the practice. Nine percent of the Class of 2024 were legacy students, meaning there were more legacies than Hispanic/Latino (7.3%), Black (5.6%), American Indian or Alaska Native (0.1%), or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (0.1%) students.

In fall 2023, Hoyas Against Legacy Admissions launched a petition to end the practice which garnered 1100 individual and 38 student group signatures. In July 2024, several Georgetown students testified in front of the D.C. Board of Education in support of a resolution—which passed—to end legacy admissions at D.C. universities. Still, the university appears loath to consider ending legacy.

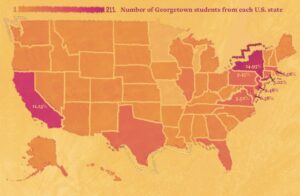

Georgetown’s rates of socioeconomic diversity are abysmal. According to a 2017 study by The New York Times, 74% of Georgetown students come from the top 20% of America’s wealth bracket, and only 3.1% come from the bottom 20%. The Voice requested up-to-date stats from the university but did not receive any.

In the past, universities have sought to recruit a more socioeconomically diverse student body by admitting more students who qualify for a Pell Grant, a grant that is given by the federal government to those displaying “exceptional financial need.” Fifteen percent of Georgetown’s Class of 2028 is made of Pell-eligible students. However, the class’s percentage of Pell-eligible students is still lower than peer institutions. Twenty-four percent of Columbia University’s and 21% of University of Pennsylvania’s Classes of 2028 are made up of Pell-eligible students.

Georgetown also is the only one of its peer schools that doesn’t currently partner with QuestBridge, a scholarship program that matches high-achieving low-income students with early admissions and a four-year full scholarship.

There are countless ways that Georgetown can make its admissions more equitable. These include ending legacy admissions and becoming a QuestBridge Partner, along with: employing class-conscious admissions; increasing financial aid opportunities; furthering outreach to rural and low-income communities; joining the Common Application, decreasing reliance on standardized testing.

While where you went to college shouldn’t be the decider of your future success, sometimes it is.

Georgetown has produced 25 governors, over 60 U.S. ambassadors, and the third-most legislators to the 118th Congress of any university. Former Hoyas have been CEOs of J.P. Morgan, Citigroup, Warner Bros., and AOL. Alumni have served as presidents of El Salvador, Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, the Philippines, and the United States of America. Hoyas currently work at almost every major news network, serve in the incoming and outgoing presidential administrations, and one was even Sexiest Man Alive.

Who goes here matters. The diversity of Georgetown and other top universities directly impacts the diversity of corporations, media, and world leaders. The desire for a diverse campus comes from a hope for a future where anyone, no matter their background, can gain the benefits of a Georgetown education—diversifying our campus and our world’s leaders.

If Georgetown wishes to avoid criticism for its lack of diversity, it could simply commit to greater standards of diversity—and the administration can look to its own campus to find brilliant minds in touch with these marginalized communities. Georgetown students spend time in classrooms, clubs, and across D.C. coming up with solutions to create a more equitable world. Students could surely use that education to create a more equitable campus, too.

Georgetown is in a time of great transition as we search for a new president and begin to navigate the end of affirmative action. Though it may be naive, I can only hope that now is the time that Georgetown may turn over a new leaf.

Georgetown admissions: the task before you is heavy, but also an incredible privilege. You have the unique opportunity to truly be people for others, enact community in diversity, and create an inclusive model of admissions that Georgetown and higher education have lacked thus far.

The choice is yours.

Editor’s Note: Sydney Carroll was briefly involved in organizing with Hoyas Against Legacy Admissions in early 2024.