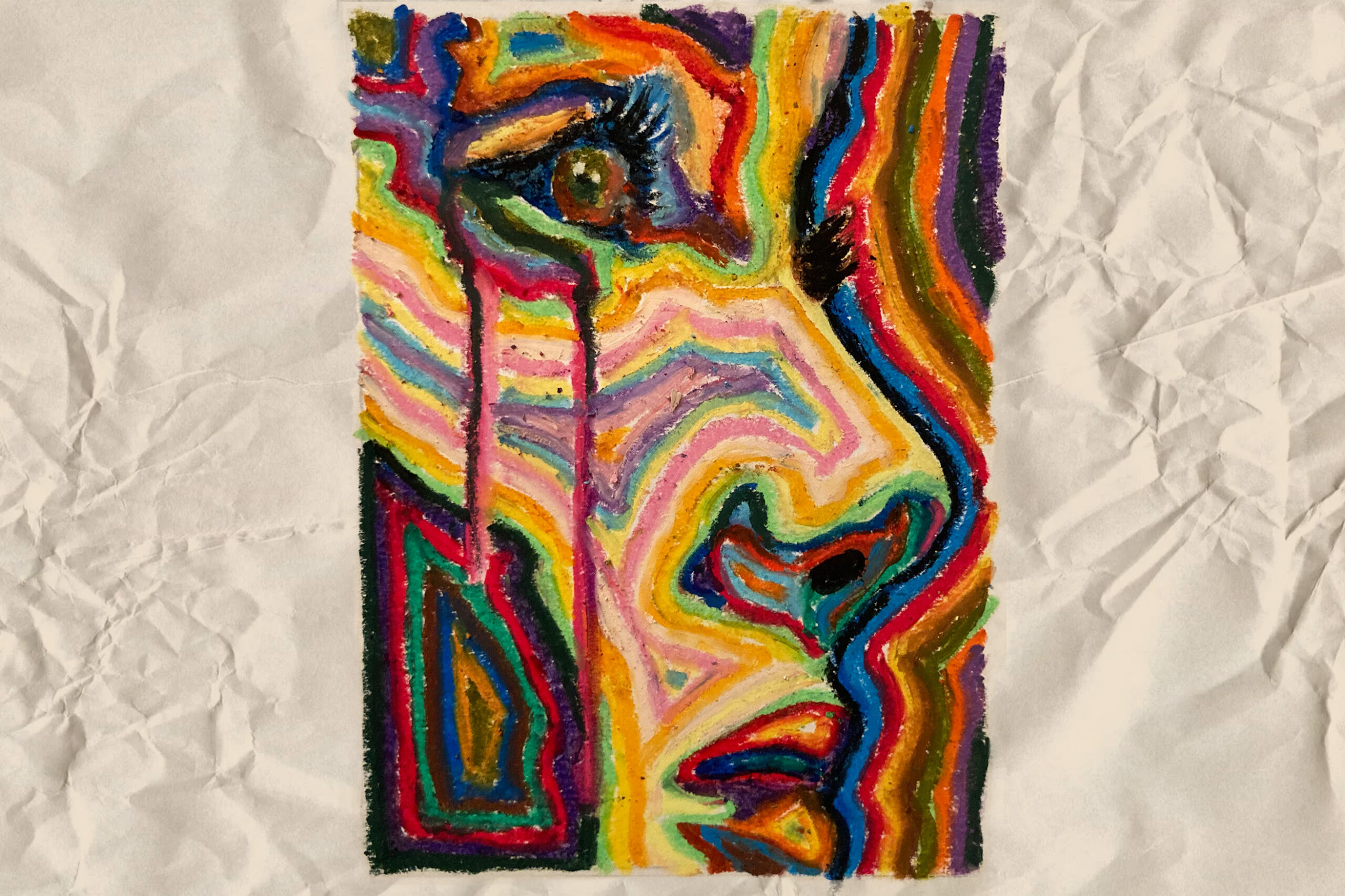

Grief is a ghost that follows me around wherever I go. Sometimes I can forget about it—I can have fun, I can enjoy myself, I can have a really good day or week or even month that makes it feel like the ghost is gone. But then, Bam. I’ll see or hear something that recalls a certain memory, like eating brussel sprouts just like the ones my dad used to cook, and it’s a full-body reminder that the hauntings don’t just end.

Grief is a nebulous concept: It’s sadness, for sure, but also can look like every other emotion in the book. Sometimes the loss of what could’ve been hurts but there are also happy memories, funny memories, memories that make you smile, even if wistfully.

In a society littered with cultural taboos around conversations about death, processing these memories and healing is slow and difficult, exacerbating the difficulties of loss. Time doesn’t heal all wounds (contrary to some of the worst advice I was given after my dad died) and can even make it harder to share. My dad died a little more than three years ago, and it feels much harder to pop this into conversation compared to when it was more recent and people around me were more familiar.

More than 20 percent of undergraduates are in their first year of bereavement. The pandemic has only exacerbated this issue: one in four COVID-19 deaths in America are parents—meaning nearly 140,000 children lost a parent or caregiver in the last two years, a crisis that most severely impacts children of color. But despite this concrete evidence that I am not the only person in bereavement, grief isn’t normalized.

Even among others processing loss, I sometimes find conversations about grief tough. Each person’s grief is their own—for better and for worse. Sophia Dembling, a writer whose husband passed away in 2020, summed it up quite nicely two years later in Psychology Today: “Grief is both universal and intensely personal.” And it’s true; though my grieving shares characteristics with others’, it is also uniquely mine.

It’s particularly difficult to reconstruct a picture of my dad nowadays for those who never knew him. They don’t know he blew his nose like a foghorn; or that he loved to grill even when it was 100 degrees outside; or that he had a favorite child (our cat, Skippy); or that he showed his love in really subtle ways, like cooking or keeping my report cards or fixing my car, that I could never appreciate while he was alive.

It is impossible to convey all of that out loud. Sometimes, the person is hard just to remember.

In other ways, it’s hard to bring up the death of a loved one without being a total mood killer. I once told someone my dad “wasn’t in my life anymore,” despite him being a) very much a big part of my life, and b) very dead, to avoid the weird emotional dynamics of “I’m sorry” and the awkward silences that come after someone finds out he passed away.

For some conversations, I just avoid bringing up his death altogether. Rather than dealing with apologies or questions, I then have to cope with feeling like I’m lying by omission. At Georgetown, for some reason, it’s common to talk about what your parents do for a living—perhaps an ode to the pre-professional culture. But at what point in a conversation discussing how my dad used to be a registered nurse is it appropriate (or necessary) for me to include he’s dead? Most of the time I don’t at all.

In a society where conversations about grief aren’t normalized, where there is this invisible barrier to communicating an essential part of life, it can be doubly hard to grieve. But to healthily process my emotions, I’ve got to be able to talk about them—or at least, be unafraid of the social consequences should I choose to. Healing from grief is a necessary life skill, both in that it is a part of life, and requisite to a healthy one.

Not that it’s the fault of those who don’t know how to react; I can understand the feeling of not knowing what to say to those who have lost someone. I’ve Googled countless advice articles to help friends experiencing similar struggles. Sure, they provide a template, and often have bits of useful advice speckled throughout—but until my dad died, it was hard for me to process the sheer scope of grief. No single article can encapsulate it.

Grief is not a one-and-done kind of deal. I wish it were. The first weeks without your loved one can be the absolute worst—adjusting to this person-sized hole in your life is not easy, nor should it be. But there’s no blood to congeal, no bandaid that could fix the hurt that stays with you for the rest of your life. There will always be moments where my grief sucker punches me in the face and it hurts just as much as the day my dad died.

But when people feel as though conversations about this pain aren’t normalized, the process of grieving—which, let me tell you, already sucks—is worsened. Grief will always be a difficult topic, but it doesn’t have to be—nor should it be—a taboo one. It can’t be, actually, if we as a society want to heal from loss.

I can’t tell you exactly how to talk about grief, or how to help a loved one that’s grieving. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution to death. Hell, it would be so much easier if there was. I certainly looked for one after my dad died.

I just ask you to approach people with empathy and not be deterred if they mention grief. Let conversations about death and deceased loved ones happen. Make them a regular part of your life. But a word of advice: Think twice before asking someone about their parents—a lot of people don’t have two. Let the person you’re talking with set the pace of the conversation—be prepared to discuss it if they want, but don’t place the emotional burden on them to explain their grief. Don’t ask why their loved one died. Why do you care? What good will my answer, which will no doubt make me a little sad, do for you?

There are billions of people in the world, all with their own personal ghosts haunting them, and unless people tell you they’re grieving, you may never know. So be consciously and intentionally empathetic.