When Megan Skinner (SFS ’24) first learned about GUSA in 2020, women filled a majority of the Senate seats.

This year, Skinner is one of only eight women in the 27-person governing body.

The now-speaker of the Senate credits GUSA’s 2020 demographics for showing her the organization’s potential. While she’s proud of GUSA’s work, Skinner has to make a conscientious effort to ensure the men leave space for women’s voices—including her own—in the GUSA Senate.

“It’s definitely a challenge to lead a room that is dominated by male voices, and strong ones at that,” Skinner said. “Making sure that my voice is respected and that other women in the Senate’s voices are heard has been incredibly important to me in my time as speaker.”

Skinner is one of many women leading student organizations on campus. However, an analysis by the Voice of 341 clubs listed on CampusGroups revealed that female leadership is concentrated in service and cultural clubs. Comparatively, Georgetown’s female students are less likely than their male peers to be elected or appointed to lead student organizations in political and business fields.

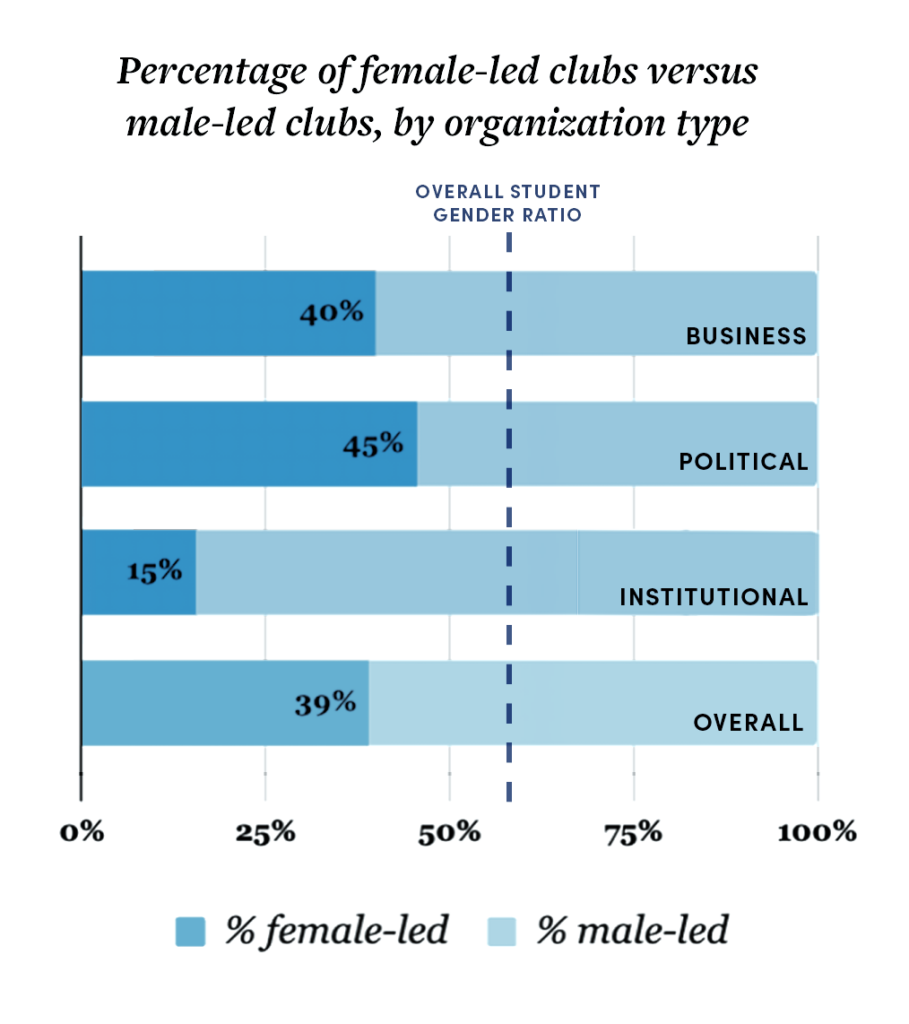

While women were slightly overrepresented overall in student leadership during the Fall 2023 semester, they made up only 39 percent of the presidents, CEOs, and directors leading Georgetown’s political, business, and institutional student organizations. Meanwhile, women comprise 55 percent of the undergraduate student body.

Only 42 percent of Georgetown’s business and political club presidents are women. Moreover, men are more than twice as likely as their female peers to run institutionalized student organizations—GUSA, academic councils, and advisory boards. On a campus where clubs are seen as instrumental to students’ university life and future careers, the people leading those organizations gain immense social and professional capital.

Michaela Cornejo (CAS ’25), president of the Georgetown Bipartisan Coalition, said that the disparity in student organization leadership is often overlooked by the larger student body.

“It’s a common conversation held on campus that there’s a woman majority,” Cornejo said. “I think a lot of people fall back on that when talking about representation and the female voice, but the fact that that’s not reflected in leadership is ridiculous.”

Without diversity in leadership, clubs may make decisions that privilege certain groups, Julie Owen, associate professor of leadership at George Mason University, said in an interview with the Voice. Because different identities often reflect a diversity of experiences and viewpoints, organizations make more informed decisions when they have more female leaders.

“Just because we have a majority of women does not mean that the majority of women are represented or our voices are being heard,” Cornejo said. “When you get into intersectionality in different demographics of women, it gets even worse.”

Georgetown’s community has not always supported women, especially women of color, seeking leadership. Women as a whole have been significantly underrepresented in GUSA’s executive branch, with a 2019 analysis by the Voice revealing that only 19 percent of presidents or vice presidents have been women. However, when GUSA elected its first female president in 1977, a woman of color did not lead the organization until 39 years later, in 2016.

Georgetown, as well as society at large, has not done enough to address the systemic barriers, including harassment and discrimination, that women face when becoming leaders, according to Nadia Brown, director of Georgetown’s Women and Gender Studies program. By failing to correct this “systematic marginalization” at Georgetown and in the U.S., leadership inequities will persist, Brown said.

Female students interviewed by the Voice said that when they do assume leadership positions in business, political, and institutional organizations, they often experience challenges—both explicit and implicit—to their authority.

Cornejo said that when interacting with other organization leaders, it’s not uncommon for men to fail to take her and her female peers seriously, or to assume they don’t have anything relevant to say. Their opinions are often quietly devalued in conversations.

“The challenges that other leaders pose to us female presidents is very tactful and very covert,” Cornejo said. “It’s very between the lines. I would say that they hide it very well, but it’s obviously still something that we pick up on.”

Some female leaders recounted times when men failed to leave adequate space for the opinions of women by talking over them or seeming to underestimate their intelligence.

At the beginning of the year, Skinner realized that the Senate’s male voices sometimes drowned out the women’s during the legislation discussion process. She decided to move these conversations from in-person to online. Her idea was that when members have equal standing on a virtual platform, everyone has an equitable chance to share their opinion.

“Now, everyone can interact with the legislation, you’re not seeing a face and you’re not necessarily hearing the loud male voices over the others’,” Skinner said.

Courtney Mawet (MSB/SFS ’24), CEO of the Hilltop Microfinance Initiative, said even when her male peers learn she leads a microfinance club, they devalue her knowledge. In classes and passing conversations, Mawet said they make the assumption that she does not understand the topic as well as her male counterparts.

Oftentimes, male peers do not even appear to realize that they are undermining the female leaders around them, the women said.

“If I were to confront them face to face, they would say, ‘Absolutely not, I would never say anything like that,’” Cornejo said. “The problem is that they don’t even realize what they’re saying.”

This unawareness may stem from the fact that many of these comments and actions—speaking over women, telling them to smile more, asking questions to male inferiors instead of female leaders—come from societally ingrained sexism, according to Brown and Owen.

While men may not realize how demographics play a role in who assumes leadership and how leaders are treated, female student leaders say they often talk about it among themselves. Cornejo recalls having conversations with female members of her board about how male leaders of other clubs interact with them. Skinner also remembers conversations with other women in GUSA about how men talk to—or over—them.

At Georgetown, people assume leadership of student organizations through several different paths, according to students and organization bylaws. Some leaders are elected through club-wide elections, while others are appointed by the previous president or chosen by their club’s executive board.

Regardless of whether they ran for the position or were selected, the female presidents of business, political, and institutional student organizations that the Voice spoke with agreed, almost unanimously, that an older female leader helped make it possible for them to assume the position.

When Viha Vishwanathan (MSB ’24) was deciding to run for Innovo Consulting’s executive directorship, her female predecessor, Sarah Chan (MSB ’23), supported her through the process.

“She spoke to me about what it’s like to be executive director, and she was a great mentor throughout deciding to apply and even now,” Vishwanathan said.

Ashley Fu (CAS ’24), CEO of Georgetown Marketing Association, had a female mentor in the club. So did Ally Paik (MSB/SFS ’26), co-president of Georgetown Aspiring Minority Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs.

Support from a strong female predecessor can help women take leadership positions, even in institutions that are overwhelmingly male-dominated. Skinner assumed the role of GUSA’s speaker of the Senate, despite men currently comprising 70 percent of the governing body. She partially credits the female speaker before her, Manahal Fazal (SFS ’24), for providing mentorship and opportunities to learn, as well as modeling how to lead.

Not only was a strong female mentor essential, but organizational demographics also played a role for some of the female leaders when they first decided to join their clubs.

During Skinner’s first year at Georgetown, the GUSA executive branch was made up of two women of color, Nile Blass (CAS ’22) and Nicole Sanchez (SFS ’24), and women comprised a majority in the Senate. This representation was a major departure from GUSA’s historically male-dominated leadership—GUSA’s first female speaker of the Senate was chosen in 2019.

While GUSA’s demographics are not as diverse as they were in 2020, Skinner said her understanding of the institution came from that formative year.

“For me, building my understanding of the institution, what it does, and what it can do, I learned that from two women, and women of color,” Skinner said.

Despite challenges, female club leaders agreed it’s critical that women are equitably represented and supported in these leadership positions. For one, many acknowledged that they bring a unique perspective to organizational discussions because of their identities.

The last two presidents of the Bipartisan Coalition were white men, Cornejo said, and part of the reason she ran for the presidency was to ensure that different demographics were represented among the organization’s leaders.

“I’m Peruvian, I’m a girl, I’m from San Francisco. I just felt it was really important to have that diversity of opinions here, especially within the leadership,” Cornejo said. “Within the club, it’s very important to not have the same demographic running over and over and over again.”

Paik emphasized that leading student organizations is beneficial for the women themselves, as well as the group they run. She argued that leadership experience can be helpful to prepare women for the professional post-grad world—giving them opportunities to try experiences as students.

The female leaders of these student organizations also see themselves as examples for other young women at Georgetown, just as previous women were examples for them.

During her four years at Georgetown, Fu said that she has struggled with imposter syndrome. As an international student, a person whose first language is not English, and a woman, she found it difficult to trust herself as a leader when she first came to campus.

“I didn’t think it was possible for me as an international student and also a woman to be the CEO of such a big, pre-professional student organization, but I did it,” Fu said. “I want to be an example and I want to help people, especially women and international students, know that you can do it.”

Being a leader includes both setting an example and providing mentorship, women interviewed by the Voice said. Skinner feels personal responsibility to foster an environment in the Senate that encourages young women to seek out leadership positions. Among these efforts, she’s worked to build mentorships within the organization to provide support.

“If there’s one thing that I want my legacy to be, it’s that I want to make GUSA a space for women, especially the Senate,” Skinner said. “We all help each other on legislation, we sponsor each other’s legislation, and promote each other for leadership positions.”

For Vishwanathan, one of the formative moments of her club leadership experience was realizing that she was an example to other women. When she was looking for a club to join freshman year, she went to an information session for Innovo. Unlike some of the other panels she had attended, Innovo’s was all women, which helped inspire her to join.

The next year, she took her first leadership position as a project manager. She remembers being nervous as a young woman leading a team of students older than her. But as the team went around the table sharing why they chose her project, a new hire raised her hand. She said she had chosen this team because Vishwanathan was a woman.

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, that’s crazy,’ because that’s also been a consideration that I’ve made in the past,” Vishwanathan said. “It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy where if you have women in leadership and women who look like you in leadership, then you’re more likely to gravitate to those clubs and leaders.”

A note on data collection:

To calculate the gender demographics of Georgetown club leadership, the Voice compiled a list of all 341 clubs registered on CampusGroups in November 2023. Organizations with members of a single gender, those without a hierarchical leadership structure, and clubs lacking listed leadership were filtered out. Clubs were sorted by type, largely based on their CampusGroups identification.

The leader of each club was identified through the platform and confirmed using official club websites, club social media posts, and LinkedIn. For each political, business, and institutional student organization the leader’s gender was confirmed by the club via email or a member of the group.