Campus brims with queer joy during October or, as the LGBTQ Resource Center has called it for at least the past decade: OUTober. As part of National Coming Out Day on Oct. 11, queer students chalked Red Square with affirming messages for their queer peers and danced through a prop “closet door” stationed in the middle of the square to symbolize coming out. They showcased their pride loudly on a campus that once forbade queer activism in campus spaces like Healy Hall.

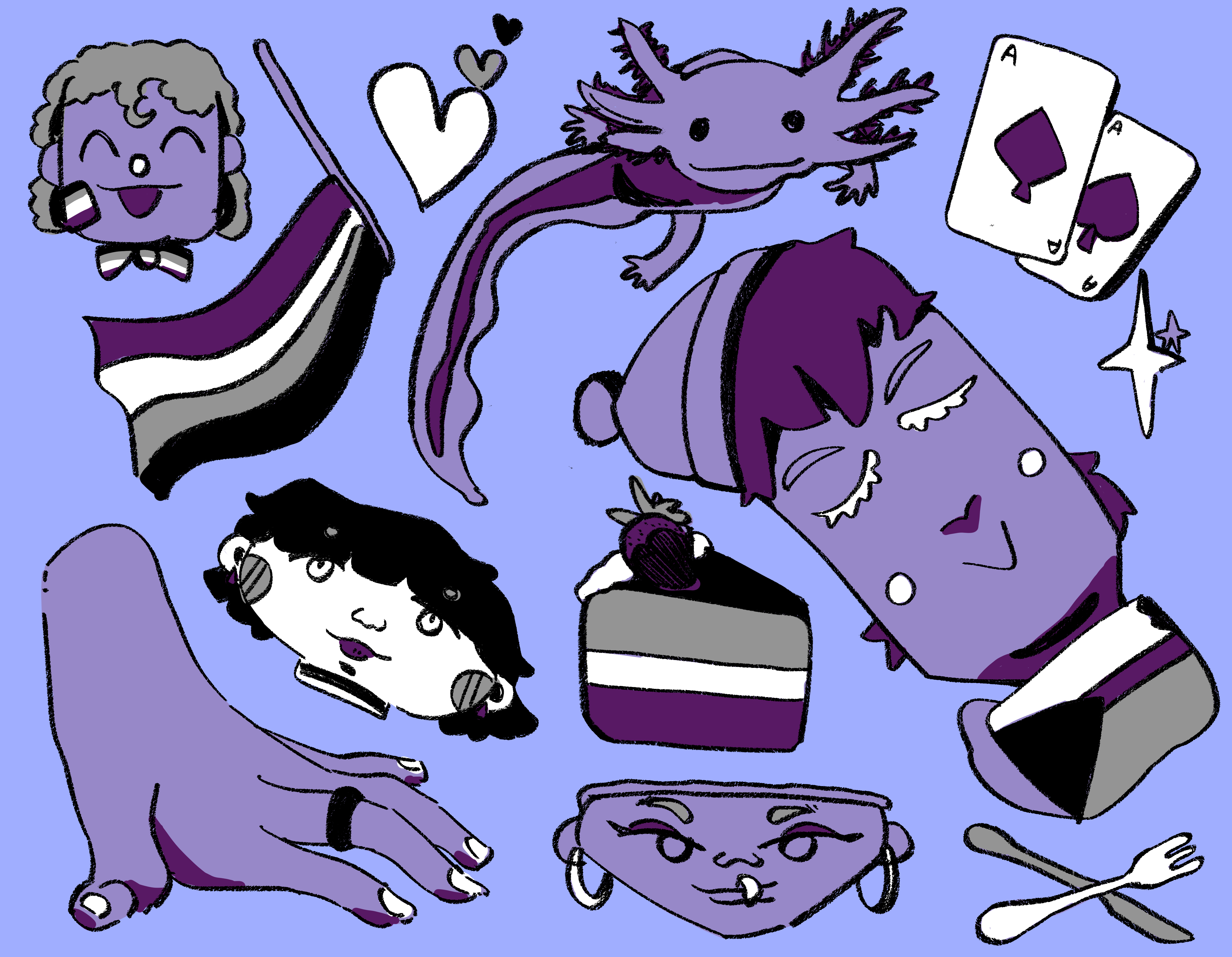

On Oct. 22, many queer students will also congregate in Dahlgren Chapel for the Mass of Belonging, a Catholic service open to Hoyas of all faith backgrounds that will create a space for queer Hoyas to celebrate both faith and LGBTQ+ identity. But the university’s recognition of queer communities of faith is not the only queer moment happening on Oct. 22. It also marks the beginning of the 12th annual Asexual Awareness Week, a week dedicated to raising awareness and education about asexuality.

According to the Voice’s 2022 sex survey, more than three percent of respondents identified as asexual. Despite this, raising awareness about asexuality—a sexuality defined by the Human Rights Campaign as experiencing little to no sexual attraction, often shortened to ace—can be hard on Georgetown’s campus, according to some asexual Hoyas. “There’s not a lot of asexual organizing,” Jack Hoeffler (CAS ’25), an asexual student at Georgetown, said, adding that for him, finding other ace Hoyas is difficult.

Other ace students felt differently, however. “I think there’s a bunch of small ace communities that then get connected later,” Gisell Campos (CAS ’25) said.

Despite their differing experiences, Hoeffler’s and Campos’s comments communicate the same principle: there isn’t a unified asexual community on campus, and thus no unified ace advocacy. Instead, ace students who choose to do so often teach others about asexuality independently through conversations with friends, participation in GU Pride, or writing in student publications.

Though they may share a label, the meaning of the ace identity is often individualized.

“I don’t really want to have sex with anyone is how I would describe it,” Allie Gaudion (CAS ’26) said. “I’ve never felt compelled to engage with myself and with someone else in a sexual manner.”

How Hoeffler views his ace identity, however, differs from Gaudion. “I often don’t feel any sexual attraction until much later into any romantic relationship,” he said.

While Hoeffler has experienced sexual attraction, this does not exclude him from the asexual umbrella. According to the Asexual Visibility and Education Network, asexuality encompasses a myriad of experiences that do not fit into the classic molds of normative allosexuality—the experience of feeling sexual attraction in non-specific circumstances—making it an incredibly diverse identity. As a demisexual person—someone who only feels sexual attraction after forming a romantic bond with someone—Hoffler exemplifies the “little” part of the “little to no” definition of asexuality.

Asexual people also differ in their romantic attraction towards others. Romantic and sexual attraction are not the same. Though people often assume that all asexual people are also aromantic—experiencing little to no romantic attraction—this is not the case. In fact, only about 41.5 percent of ace people identify as being on the aromantic spectrum as well, according to the Ace Community Survey. Others identify as heteroromantic, homoromantic, or biromantic (amongst other romantic identities), regardless of their sexuality.

This diversity is reflected in Georgetown’s ace community. “I explain to people that I do feel a very strong romantic attraction,” Hoeffler said.

For Campos, their romantic identity and their asexuality are inextricably linked. “[Asexuality is] a tag to put on yourself in a way that’s different than other labels,” Campos said. Though they came out as lesbian at the age of 12, “I wouldn’t say that I’m not a lesbian, but I also would say that I am ace. I feel like those are things that aren’t necessarily exclusionary of each other.”

Another asexual student, who asked to remain anonymous as they are still exploring their sexuality, however, feels differently. In regards to how they would feel if they got asked out on a date, they said that they would feel “bone-deep nausea, just like chills and like ‘I might puke right now.’”

Though it may then seem too all-encompassing to refer to all these different experiences as “ace,” people under the ace umbrella share their position outside of allonormative expectations within relationships. “One guy told me, ‘Sex is what makes you feel the most alive,’” Gaudion said. “I’m like, ‘Whoa, no.’”

For Hoeffler, his disconnect from allonormativity manifested during the beginnings of his relationship. “[My girlfriend] was insulted at the idea that I wasn’t physically attracted to her when we first started dating,” Hoeffler said. Both Gaudion and Hoeffler were unable to feel the sexual attraction that they felt their partners—and society—expected them to experience.

The diversity in experience for ace people is what so many want allosexual students on Georgetown campus to know about asexuality.

In interviews with the Voice, ace students repeatedly referenced two distinct spectrums of asexuality embraced by their community. First, the amount of sexual attraction someone has felt throughout their lives (also known as the asexual spectrum); and second, the level they are comfortable with sex, ranging from sex-repulsed to sex-favorable.

“It’s important to recognize that it’s a spectrum and that there are people that are at different places of that spectrum,” Campos said. “It’s not really a static thing.”

Many asexual people see the spectrum of their sexuality as continually evolving. The spectrum theory—that sexuality can ebb and flow over time—can be applied to all sexualities, not just asexual ones.

“With any sexuality, [there’s] a spectrum and your feelings change,” Gaudion said. “Or maybe not, and that’s okay.”

“I think that people look at labels more as a diagnosis rather than a descriptor. And I think that should change. Because it’s not saying, ‘You can’t do this because you are this.’ It’s saying, ‘I feel this way, and I’m gonna call it this because it makes it easier to describe.’ But it’s not something that you have to stay in,” the anonymous asexual student said.

For Hoeffler, Asexual Awareness Week is important because of the way that asexuality is often misunderstood. “The prejudices we face as asexuals [are] more about understanding and the lack thereof,” Hoeffler said. “I think it’s hard to navigate that as a group because you’re not necessarily pushing against a very open sort of oppression, but more so very subtle perceptions of identity and relationships.”

In interviews with the Voice, many asexual students recounted moments of their identity being directly invalidated. Campos recalls explaining asexuality to their mother. According to Campos, she responded by saying, “I don’t think that’s a thing.”

The anonymous asexual student reported experiencing frequent asexual erasure. “Every single time you bring it up, people are like, ‘Oh, well what if you just haven’t met the right person yet?’ And it’s like, ‘Yeah, what if?’ But here I am,” the student said. “At some point, you can, beyond reasonable doubt, be like, ‘I think this is what’s going on.’”

This experience is not unique to Georgetown’s ace students. According to the 2020 Ace Community Survey, about 45 percent of ace people report experiencing “excessive or inappropriate personal questions about their sexual or romantic orientation,” and roughly 40 percent reported being told that they can be “fixed” or “cured.” When asked about the impact that discrimination may have had on respondents’ mental health, 13 percent said that it “had a major effect.”

Other forms of harm toward asexual individuals, however, are far more explicit. When Gaudion came out as ace in high school, she was being sexually pressured by her partner, despite openly identifying as ace. “My partner at the time was still pressuring me to have sex, and pressuring me if I changed my mind,” Gaudion said. This is not an atypical case. In the 2020 Ace Community Survey, 13 percent of respondents reported experiencing sexual harassment due to their sexuality, both in person and online.

Society’s general emphasis on romantic and sexual relationships can also act as a mechanism of pressuring ace people to conform according to Angela Chen, a journalist who identifies as asexual. In her book “Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex,” she argues that everyone—from media to the medical establishment—emphasizes sex and relationships in a way that causes asexual people to be alienated. This sentiment was echoed by ace students at Georgetown.

“A lot of people put a lot of emphasis on romantic relationships as being the ultimate form of a relationship, right? And then everything else just sort of seems lesser,” Hoeffler said. “I think that for, especially [aromantic asexual] people, [that] puts a lot of unordinary pressure to be understood in that environment. And I think a lot of people struggle with that.”

This societal norm pressures asexuals who are not aromantic as well. Multiple ace students expressed often feeling as though they are expected to engage in sexual activity.

“When I say I’m going on a date, they’ll be like ‘Oh, don’t do anything hinky,’ or insinuate that something sexual will happen in my romantic encounters. And it’s like ‘No, that’s not really my priority in a relationship,’” Gaudion said.

“There’s a lot of pressure on you to follow through on what you promised kind of thing, you know? Like there’s a lot of that kind of, ‘Oh, she’s a tease’ kind of mentality,” the anonymous asexual student said.

According to Hoeffler, however, many ace people believe that non-romantic relationships should take equal precedence for society. “Their friendships and their relationships and their queer platonic relations … are not necessarily lesser,” he said.

To the anonymous asexual student, all people, even allosexual individuals, could benefit from realizing that romantic relationships are not superior.

“A lot of people enter into relationships that are really unhealthy for them or that they don’t necessarily want to be in it because they are afraid of being alone, or they don’t know how to be alone, or they think that they are somehow worth less because they’re not currently in a relationship with somebody,” they said.

“Your romantic relationships shouldn’t necessarily take priority over your friendships,” they added. “I think it would be a healthier state for just all of us.”

Though Asexual Awareness Week was created in 2010 by Sara Beth Brooks to improve ace visibility, its focus has shifted to bringing ace people together to celebrate their identity.

“People get to be proud about being ace just as much as they get to be proud about being trans, or proud about being gay, or proud about being a lesbian. So I think that ace people not only deserve to take up space, they should be taking up space,” Campos said.

There have been only a handful of articles about asexuality published in Georgetown student publications in the past two years. When pieces are published, though, they can be deeply impactful for the ace community. “Reading content that Georgetown students produce about being queer and being ace and being all of these things at once has been incredibly validating,” Gaudion said.

As Ace Awareness Week approaches, Gaudion hopes to promote ideals of ace joy and queer solidarity. “For anyone who reads [this], you’re so valid and you’re slaying and I’m very proud of you.”