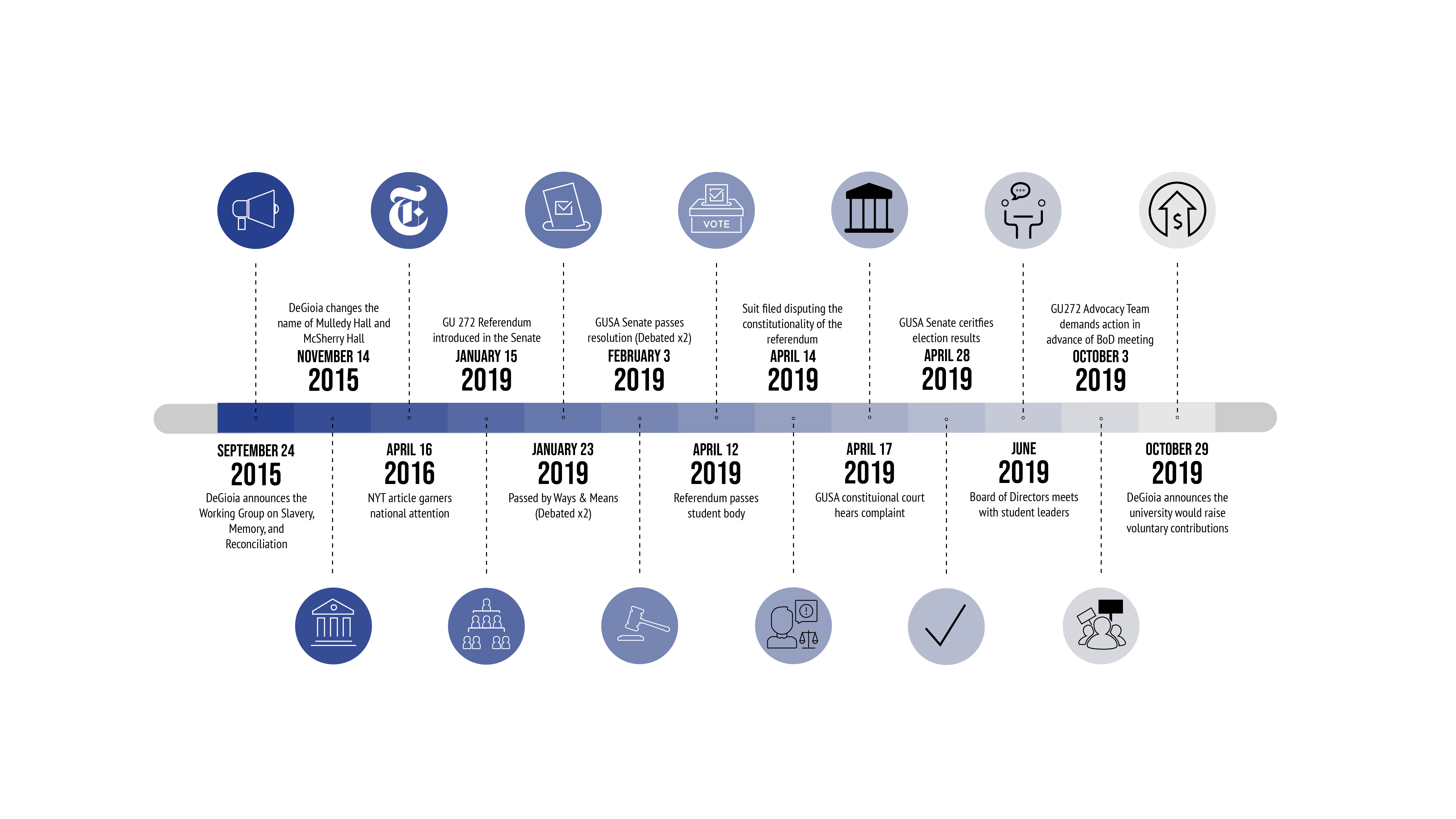

Since Georgetown University’s long history with slavery re-entered public view five years ago, faculty, administrators, student activists, and descendants of those enslaved by the Jesuits have grappled with the significance and trauma of this history and its implications for the university today.

A landmark referendum to pay reparations to the descendants of 272 enslaved people sold by the university in 1838 is the most prominent effort to reckon with the legacy of slavery on Georgetown’s campus. However, after it was passed by the student body, the effort effectively stalled with the university Board of Directors.

The Georgetown Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation Project is still uncovering ways in which Georgetown perpetuated and upheld the institution of slavery, and student activists, faculty, and independent researchers continue to advocate for reparative justice.

Georgetown’s History with Slavery

According to the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation commissioned by University President John DeGioia in 2015, “Georgetown University’s origins and growth, and successes and failures, can be linked to America’s slave-holding economy and culture.”

The Jesuits of Maryland, who ran Georgetown in its first decades, owned and operated plantations throughout Maryland that ran on enslaved labor. Profits from these plantations were funnelled into the university, and given the region’s agricultural profile, it is likely that some wealthy families who donated to the school were themselves enslavers.

As national tensions over the continued existence of slavery grew throughout the 1800s, the Georgetown community overwhelmingly advocated for its preservation. Eighty percent of Georgetown College alumni who ended up fighting in the Civil War fought for the Confederacy.

“The general attitude of Jesuit faculty and students favored slavery as at least a necessary evil,” the Working Group’s 2016 report reads.

In the early 19th century, an estimated 10 percent of people on campus were enslaved, many of them taken from the bustling slave port of Georgetown. Enslaved people are believed to have built all of Georgetown’s oldest buildings, including the ones now called Isaac Hawkins Hall and Anne Marie Becraft Hall.

The GU272

The most notorious incident of Georgetown’s history with slavery is the sale of 272 enslaved people, known today as the GU272, by the Jesuits of Maryland in 1838. To keep the university financially viable, two of Georgetown’s early presidents sold these men, women, and children for a total of $115,000—roughly $3.3 million in today’s money.

Shepard Thomas (COL ’20), a descendant of the 272, asks the Georgetown community to consider the sale’s implications for the university today.

“I feel that we as people cannot overlook the fact that there would be no Georgetown University without the involuntary sale of these people,” he wrote in an email to the Voice.

The story of the 272 doesn’t end in 1838. After being sold to Louisiana enslavers in the South, many were separated from their families and sent to other plantations.

Independent genealogists, Georgetown faculty, and students picked up the trail in 2015 after student protests over two campus buildings named after the Jesuits who organized the 1838 sale. After five years of searching, around 9,000 living descendants have since been identified, many of whom still live in Louisiana.

A 2016 New York Times article thrust their search into the national spotlight, detailing the 1838 sale and asking what Georgetown owes to the 272’s descendants. The flurry of publicity surrounding the article added urgency to Georgetown’s internal reckoning.

On-campus Legacy

When Georgetown renovated the then-called Mulledy and McSherry Halls in 2015 to create space for more student housing, it prompted a new investigation of their namesakes. The pair, Rev. Thomas F. Mulledy, S.J. and Rev. William McSherry, S.J., orchestrated the 1838 sale and both served as university president during their lives.

In response to the new scrutiny, DeGioia convened the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to investigate Georgetown’s history with slavery and make recommendations about how to acknowledge and memorialize it.

History professor Fr. David Collins, S.J., chair of the group, described it as an opportunity to account for Georgetown’s past.

“It’s a way in which we can all be drawn into a conversation where we have to use the first person,” he said. “We have to talk about: this is what we did. This is about our history. What are we going to do about it?”

Following student protests, a sit-in, and the Working Group’s recommendation, DeGioia announced in November 2015 that the buildings would be temporarily renamed Freedom and Remembrance Halls.

In 2017, the halls were renamed Isaac Hawkins Hall and Anne Marie Becraft Hall to honor the first enslaved man listed on the 1838 bill of sale and a nun who founded one of Washington D.C.’s first schools for Black girls, respectively.

Around the same time, GUSA senators and student activists began pressing the university to follow through on the Working Group’s recommendation of building a memorial to the 272. Despite their efforts, no such memorial has yet been built.

The GU272 Referendum

Over the next few years, the university community continued to investigate Georgetown’s history with slavery. After the university formally apologized and offered preferential admissions status to descendants similar to that given to legacy students, the topic of monetary reconciliation arose.

The Isaac Hawkins Legacy Group, composed of Hawkins’ direct descendants, called on Georgetown in February 2018 to repay them for their enslaved ancestors’ labor. “They have asked for something tangible to help them deal with those needs that arise from their connection to Georgetown’s involvement in the slave trade,” wrote a spokesperson for the group in an email to the Voice.

Over the summer of 2018, a group of students visited Maringouin, Louisiana, near one of the plantations to which some of the 272 were sold. Through conversations with descendants, many of whom still live in communities in and around Maringouin, they were inspired to bring the question of reparations to the student body.

When the students returned to campus that fall, they founded the GU272 advocacy team, which strives to represent and elevate descendants in university education, memorialization, and reconciliation efforts. Their efforts gained traction in January 2019, when then-GUSA Senator Sam Appel (COL ’20) introduced a resolution based on their activism before the GUSA Ways and Means Committee.

Also sponsored by the GU272 advocacy team, the resolution called for a referendum on the creation of a reconciliation contribution to benefit the descendants of the 272. The contribution was to be similar to the student activities fee, collected once a semester in students’ tuition bills. It would start at $27.20 to honor the number of enslaved people the university sold and would rise according to inflation.

The money would then be used to benefit identified descendants through funding causes and proposals aimed to especially help descendants who continue to reside in underserved communities.

“As students at an elite institution, we recognize the great privileges we have been given, and wish to at least partially repay our debts to those families whose involuntary sacrifices made these privileges possible,” the resolution reads.

Advocacy team members Hannah Michael (SFS ’21) and descendant Mélisande Short-Colomb (COL ’21) were the first non-GUSA senators to sponsor a resolution in the governing body’s history. On Jan. 23, the resolution passed the Ways and Means Committee unanimously.

With the addition of an amendment to create a GU272 Reconciliation Board of Trustees composed of both students and descendants to oversee and allocate the fund, the resolution was put to the full Senate. Debate there also proved contentious, as some senators argued that today’s Georgetown students are not responsible for the university’s actions nearly 200 years ago.

Sen. Samantha Moreland (COL ’21), who took up the bill after Appel resigned for unrelated reasons, countered with the fact that the resolution’s passage would not create the fund, only pose the question of its creation to the student body.

Moreland closed the final GUSA debate on the bill by expressing her concern that if the resolution did not pass, the student body’s opportunity to address the 1838 sale would be lost. “If I leave this meeting and this doesn’t pass, I’m going to have a different perspective on this school, this Senate,” she said.

The resolution, which required a two-thirds majority of all senators, passed 20-4 in the GUSA Senate’s Feb. 3 meeting.

In the two months between the vote in GUSA and the vote on the referendum itself, critics and advocates of the fund both launched fierce campaigns for their side, posting flyers across campus and plastering social media feeds with their arguments.

When the referendum results rolled in early on April 12, a clear majority of students supported the reconciliation fund. Sixty-six percent of voters were in favor, a victory margin of more than 1,200 votes, with a record voter turnout of 57.9 percent.

After a brief constitutional scuffle—Rowan Saydlowski (COL ’21) and Chris Castaldi-Moller (SFS ’21) filed a suit alleging improper conduct by Sen. Dylan Hughes (COL ’19) and the GUSA Election Commission and challenging the constitutionality of a non-amendment referendum—the Senate upheld the referendum results in April 2019.

GUSA executives Norman Francis, Jr. (COL ’20) and Aleida Olvera (COL ’20) celebrated the passage as a meaningful step towards addressing the trauma Georgetown inflicted upon the 272 and their descendants.

“If implemented by University officials, the measures advanced in this referendum would put Georgetown on the right side of history and constitute the first reparations policy in the nation,” their statement read. “Despite our excitement at this outcome, it is important to emphasize that the results of this vote (as with any student referendum) are non-binding, and the GU272 proposal will require approval by the Georgetown Board of Directors before becoming policy.”

Stalled Out

Since the referendum results were referred to the Board of Directors in April 2019, little concrete action has been taken.

Board members met with student leaders in June 2019 to discuss the referendum and its objectives. “The Board plans to engage in follow-up discussions with student leaders,” the university stated after the meeting.

By October 2019, Georgetown had not announced a plan of action, despite the looming deadline to fund projects for the 2020–2021 academic year. Student activists protested the Board’s October meeting, holding signs that read “Implement the Referendum” and “Respect Our 2541 Votes.”

Weeks later, DeGioia outlined the next steps for the Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation Project. In lieu of the $27.20 reconciliation contribution from all students, he proposed a fundraising effort to support projects benefiting descendants, promising it would meet or exceed the funds collected from the mandatory contribution.

“We embrace the spirit of this student proposal and will work with our Georgetown community to create an initiative that will support community-based projects with Descendant communities,” DeGioia wrote. “The University will ensure that the initiative has resources commensurate with, or exceeding, the amount that would have been raised annually through the student fee proposed in the Referendum, with opportunities for every member of our community to contribute.”

The proposal was swiftly met with criticism by descendants and advocacy team members, who claimed that the university was attempting to replace reparative justice with philanthropy. “Reconciliation is simply not charity,” Students for GU272 wrote in a Facebook post.

“The GU272 referendum is the vehicle through which 2,541 students have committed to engage in reconciliation,” they wrote. “And Georgetown university is actively denying our voices.”

The university has not provided details on how the plan will be implemented or how much it has raised, though projects benefiting descendants are supposed to be funded beginning in the 2020-2021 academic year.

In the meantime, the Georgetown Slavery Archive, part of the Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation Project, has continued to unearth more of Georgetown’s history with slavery.

Faculty and student researchers have rediscovered and compiled information on the 1838 sale, archival materials from the Maryland Jesuits and early Georgetown administrators, and interviews with descendants, all of which can be found on their website.

Criticism over university inaction was renewed over the summer of 2020, when the disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide protests over the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black Americans underscored deep racial injustice in the United States.

To prepare for another semester of pressuring administrators, the advocacy team updated their demands this June: Implement the GU272 referendum, create a commission to study and develop plans for financial reparations, and cut Georgetown’s ties with the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD).

“The university’s relationship with the MPD points to the continued violence experienced by Black students at this school,” the advocacy team wrote, arguing that MPD’s presence on and around campus creates an unsafe environment for students of color.

While the university’s current contract with MPD is not publicly available, GUPD’s website states that it “enjoys a close professional relationship with the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department.”

Descendants and student activists also took to social media to renew their demands for action. “As a soon to be graduate and a direct descendant of the GU272+, it is disgraceful that the board has not honored the vote that took place in April of 2019,” Thomas wrote on Facebook.

“In the end, the student body and I will be on the right side of history. It’s time for Georgetown university to choose their position.”

[…] Georgetown Explained: The GU272 […]